I recently returned from leading a group of 36 friends on a European tour. We visited seven countries in 15 days. It was among the best trips I have ever experienced. Every day was full of memorable moments.

I recently returned from leading a group of 36 friends on a European tour. We visited seven countries in 15 days. It was among the best trips I have ever experienced. Every day was full of memorable moments.

We did have one regrettable moment in Rome.

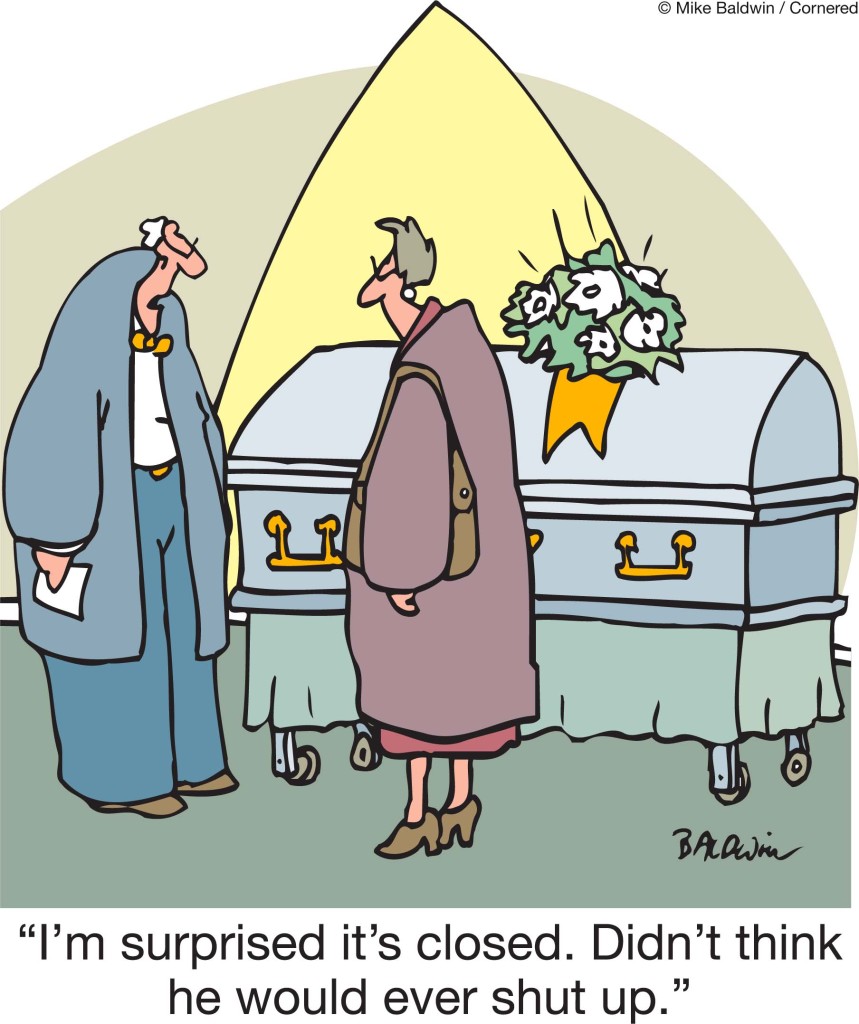

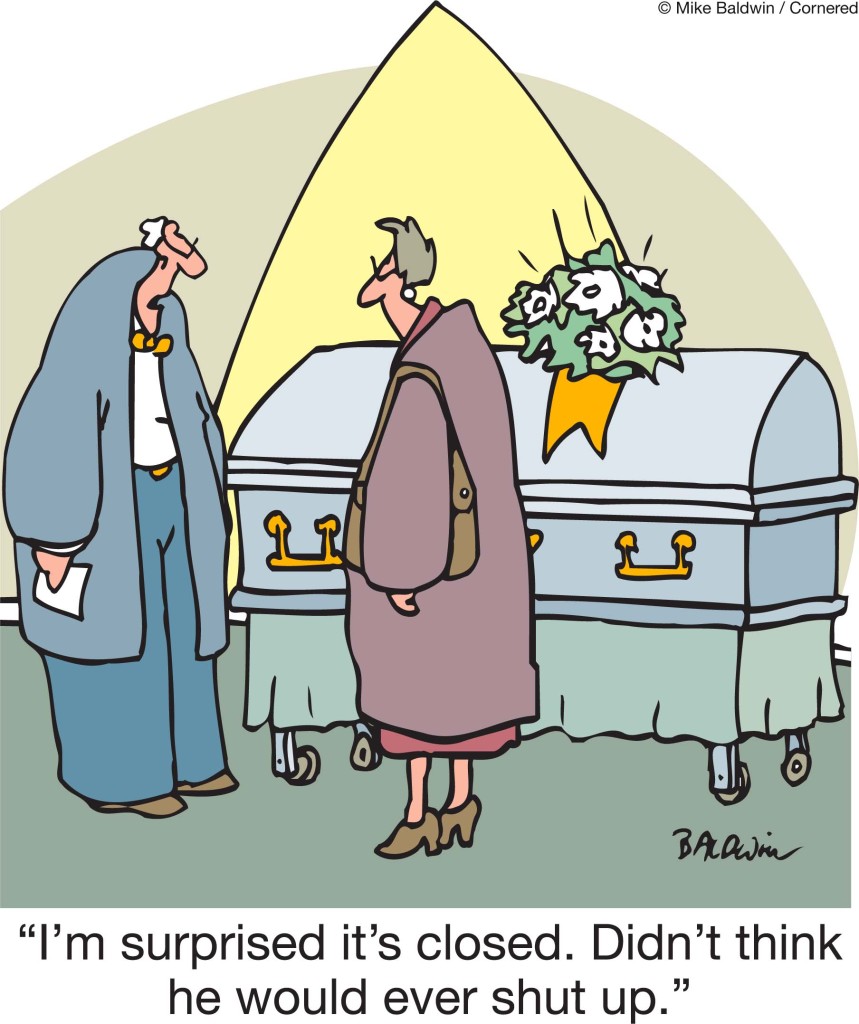

Our tour guide in Rome had an encyclopedic knowledge of Rome. Her recall of dates, history, people, and events was amazing. And she spoke passionately. But she talked too much. She gave too much detail about each sight. People can only digest a limited amount of information at a time. Her commentary was so dense, and delivered so quickly, that we couldn’t process it.

Mid-day I realized that her unreasonably long commentaries were throwing us off schedule. We had only one day to see the Roman ruins (Colosseum, Forum) and the Vatican (Museum, Sistine Chapel, Basilica) and we were running out of time.

My favorite building in the world is St. Peter’s Basilica. It is immense, beautiful, inspiring, and astonishing. Seeing it was to be the climax of our trip. But when we finally stood in front of the church our tour guide said, “Be back here in five minutes.”

Five minutes? Are you kidding? We had been victimized by our tour guide’s curse of knowledge.

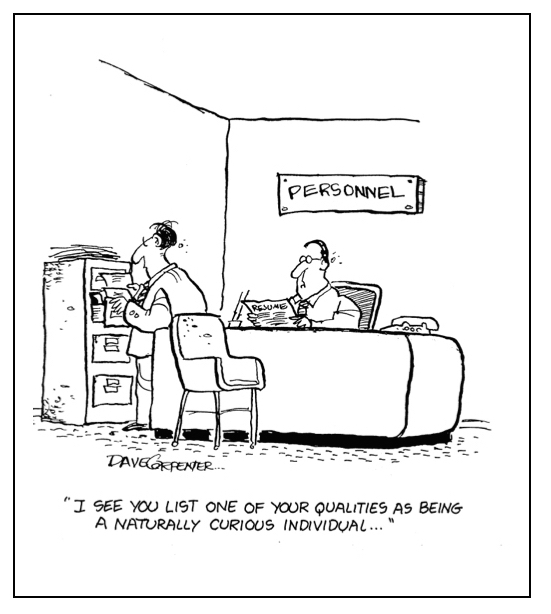

Previously I wrote a post—The curse of knowledge—in which I suggested that one type of “curse of knowledge” occurs when a person has such mature and advanced knowledge in a specific area that he cannot remember what it’s like to not have this knowledge. This makes it harder to identify with people who don’t have this knowledge base. It also inhibits our ability to explain things in a manner that is easily understandable to someone who is a novice.

In this post I’m suggesting that our knowledge can also be a stumbling block (curse may be too strong a word) when we’re insensitive about how much knowledge is appropriate to share at a particular time.

While in Rome, I admired the tour guide’s immense knowledge, but she grossly misjudged how much we were interested in hearing, how much we could digest at one time, and how her excessive commentary would affect our schedule.

This social faux pas is more common than we think.

-

- Have you ever asked someone a question, desiring a simple, short answer, but you get a long, complicated one? The person drones on and on, getting stuck in unnecessary minutia.

- Have you ever read a book that is just too detailed? For instance, I love New York City so when I heard that David McCullough wrote a book about the Brooklyn Bridge I bought it. But after reading only 25 out of 608 pages I abandoned the effort; I don’t want to know that much about the bridge.

- Did you ever have a teacher that knew his subject well but delivered too much information too quickly? In college I took a math class that was advertised as a course for non-math majors, but the professor went so fast that most of us were lost 10 minutes into the first lesson. Bad teacher. I dropped the course.

Often, we’re the victims of this particular expression of the curse of knowledge, but sometimes we’re the perpetuators.

Back to the trip. After we finished that day’s tour of Rome we shared a delightful meal together at an open-air restaurant on Piazza Navona. My table shared a nice bottle of Chianti Classico red wine. Knowing that I’m a wine expert, someone casually asked me, “Don, what do you think of the wine?” I proceeded to give a three-minute lecture on the Sangiovese grape, unique aging requirements, etc. I soon realized I was sharing too much knowledge; a simple “This is a terrific wine; the grapes are grown locally” would have sufficed.

Let’s be more self-aware of how much information is desirable and needed in conversations.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

In medio stat virtus (Latin)

In medio stat virtus (Latin)

You’re a different person at different stages of your life.

You’re a different person at different stages of your life. I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space. Hamlet

I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space. Hamlet I recently returned from leading a group of 36 friends on a European tour. We visited seven countries in 15 days. It was among the best trips I have ever experienced. Every day was full of memorable moments.

I recently returned from leading a group of 36 friends on a European tour. We visited seven countries in 15 days. It was among the best trips I have ever experienced. Every day was full of memorable moments.