I asked a friend about his experience at a chamber music concert. His first response (and his only response until I pressed him) was, “During the final song there was a terrible, loud noise that just ruined the concert. I’m not even sure where it came from.” I asked him about the other 57 minutes (the concert lasted an hour). “Oh, the rest of the concert was terrific. Beautiful music played well.” Interestingly, he chose to remember the negative part of the evening, though it represented only a small fraction of the total event.

I asked a friend about his experience at a chamber music concert. His first response (and his only response until I pressed him) was, “During the final song there was a terrible, loud noise that just ruined the concert. I’m not even sure where it came from.” I asked him about the other 57 minutes (the concert lasted an hour). “Oh, the rest of the concert was terrific. Beautiful music played well.” Interestingly, he chose to remember the negative part of the evening, though it represented only a small fraction of the total event.

I asked a friend about her vacation. Her first response was, “When we checked out of the hotel, they tried to stick us with a surcharge that we had not agreed to. I had to escalate the situation to the general manager to get it resolved. It was a very distasteful encounter.” I then asked about the previous six days and 12 hours. “Oh, we had a great vacation,” she said, “very relaxing and satisfying.”

Notice that my friends chose to focus on how their experience ended and fixated on a negative aspect. We all tend to do this.

We are inclined to remember how an event ended.

In a psychological research project, subjects each immersed a hand in iced water at a temperature that causes moderate pain. They were told they would have three trials. While the hand was in the water the other hand used a keyboard to continuously record their level of pain. The first trial lasted 60 seconds. The second trial lasted 90 seconds, but in the last 30 seconds the water was slowly warmed by 1 degree (better but still painful). For the third trial, they were allowed to choose which of the first two trials was less disagreeable, and repeat that one.

Eighty percent of the subjects who reported experiencing some decrease in their pain in the last 30 seconds of the second trial chose to repeat the 90-second experience. In other words, they chose to suffer for an additional 30 seconds because the ending of the experiment was more satisfying.

Many similar experiments have revealed that people’s remembrance and assessment of an experience are based on the peak (best or worst moment) and how the experience ended.

We are inclined to remember negative events more than positive ones.

We are predisposed to allowing negative experiences to impact us more than positive ones—an inclination we must actively work to resist. For instance, when the stock market suddenly drops and we lose money, that impacts us more than all the months in which the stock market gradually rose. This may cause us to rashly (and unwisely) sell our stocks and make us reluctant to invest in the market again.

The antidote for both dilemmas is reflection and gratitude. After an event is over (and even when it’s happening) take time to reflect on the entire affair (concert, vacation) and balance the positive with the negative. Thoughts and expressions of gratitude help us concentrate on positive aspects, which enhances and lengthens their influence.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

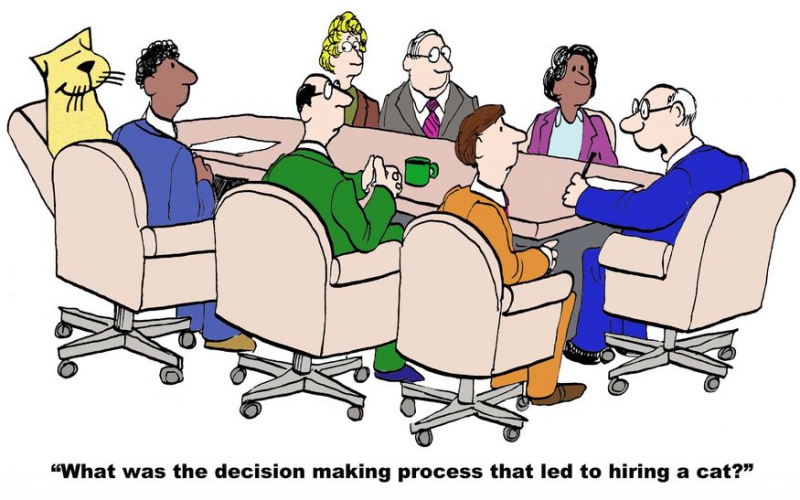

All of us are smarter than one of us—unless you’re dealing with an issue that “all of us” know little or nothing about and “one of us” knows a lot. Sloman and Fernbach

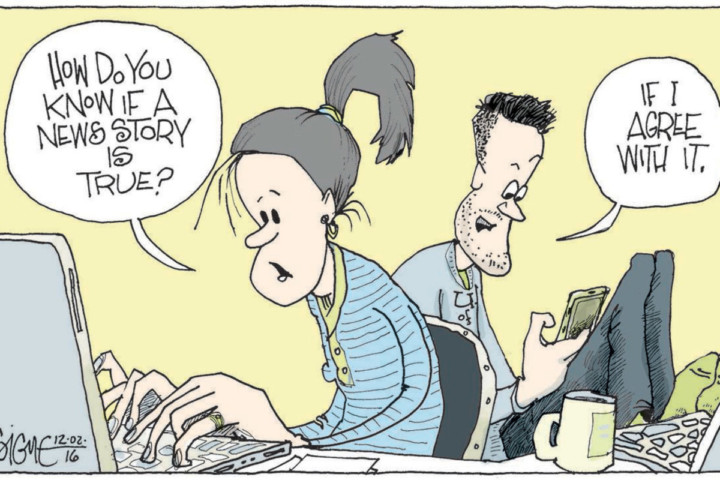

All of us are smarter than one of us—unless you’re dealing with an issue that “all of us” know little or nothing about and “one of us” knows a lot. Sloman and Fernbach In December 2016, a screenwriter named Edgar Welch read online that Comet Ping Pong, a pizzeria in Washington D.C., was harboring young children as part of a child abuse ring led by Hillary Clinton. Welch believed the false conspiracy theory and took it upon himself to visit Comet Ping Pong, unleashing an AR-15 rifle on the workers there. By some miracle, no one was hurt and the police arrested him. He was snookered by fake news.

In December 2016, a screenwriter named Edgar Welch read online that Comet Ping Pong, a pizzeria in Washington D.C., was harboring young children as part of a child abuse ring led by Hillary Clinton. Welch believed the false conspiracy theory and took it upon himself to visit Comet Ping Pong, unleashing an AR-15 rifle on the workers there. By some miracle, no one was hurt and the police arrested him. He was snookered by fake news.

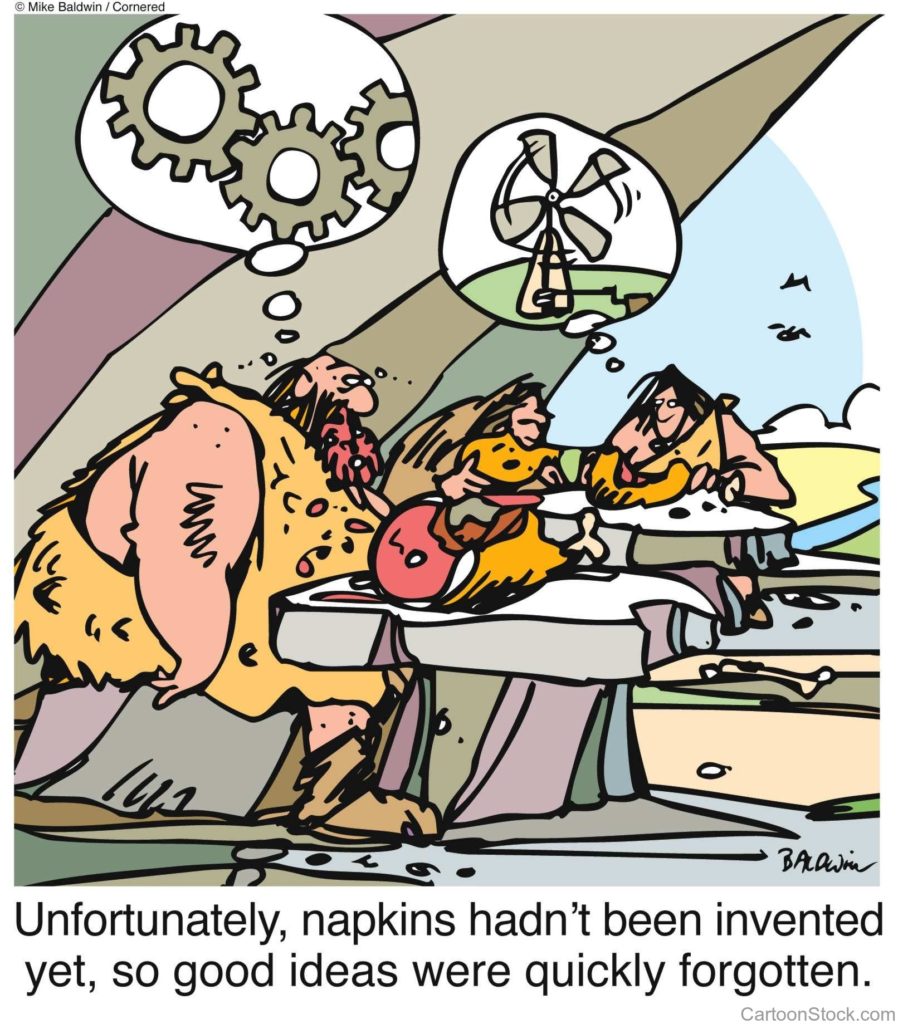

Capture good thoughts, even if you’re not sure how they might help in the future. —Andrew Hargadon

Capture good thoughts, even if you’re not sure how they might help in the future. —Andrew Hargadon