I recently had a tiff with my adult daughter. I had asked her opinion about a particular statement and when she responded, I pushed back on her thinking. She replied, “Dad, why do you ask my opinion and then argue with it?”

I recently had a tiff with my adult daughter. I had asked her opinion about a particular statement and when she responded, I pushed back on her thinking. She replied, “Dad, why do you ask my opinion and then argue with it?”

This same type of conversational misunderstanding also happened at work. Having analyzed this problem, I realize that in these situations I have been miscommunicating my intent. I need to be more clear about the type of conversation I’m wanting to have. When initiating certain conversations—particularly when I’m asking for input—I now consider three options.

Scenario 1—What is your opinion?

When I ask for someone’s opinion, I shouldn’t disagree with or challenge their thoughts. I just need to listen carefully. If I ask someone, “What did you think about the political debate that was aired last night?” that’s not an invitation to discuss politics. I shouldn’t counter what is said, I simply need to listen.

This is passive conversation; while differing opinions may be expressed, there should be no pushback or resistance. The conversation is informative but not challenging.

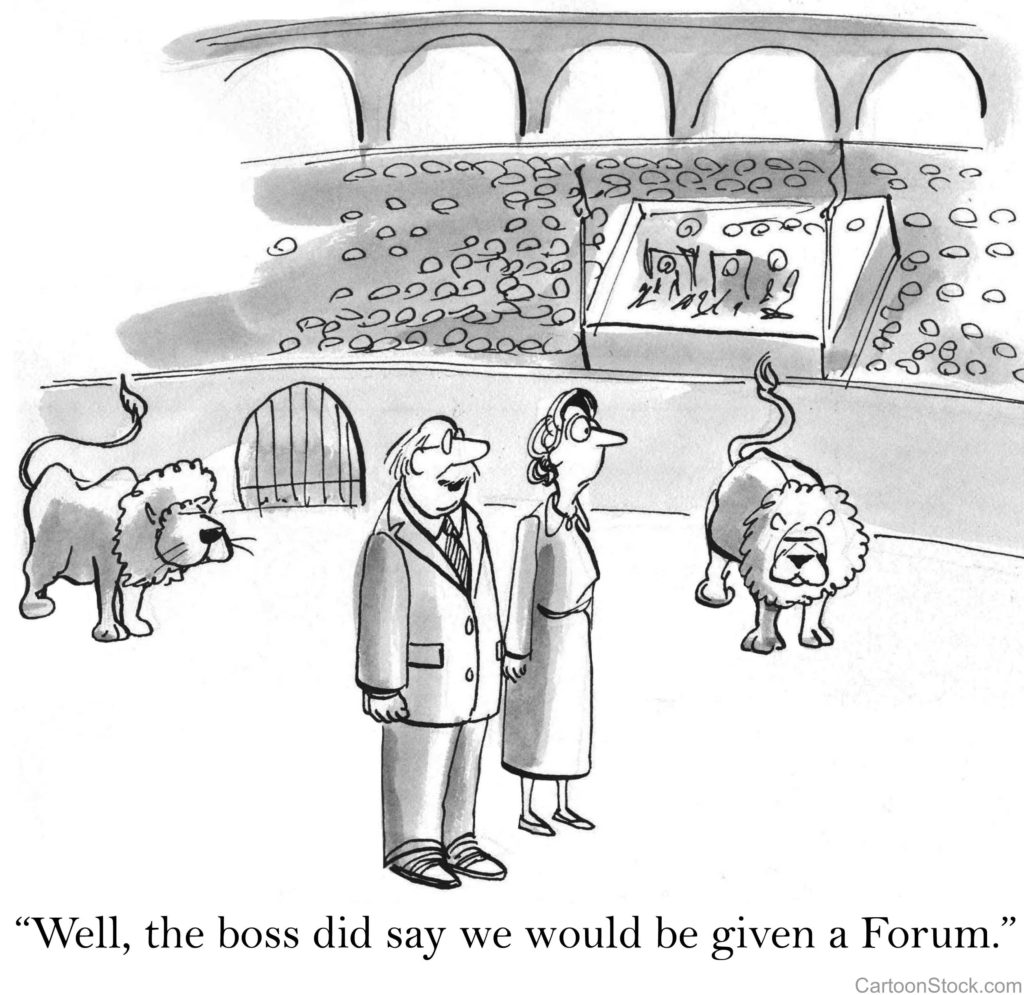

Scenario 2—Let’s have robust discussion about a particular topic.

In this scenario, I’ll seek your opinion but I’ll feel free to challenge your thoughts and you can challenge mine. I’m wanting to dig deep into a subject, not to prove who’s right and who’s wrong, but to better understand a situation. Let’s challenge each other and we’ll both end in a better place. The goal is not to win an argument but to learn. I will probably begin the conversation with a slight inclination but not a firm position. At the end of our discussion I may think differently. But I need to wrestle with our thoughts to get there. I will challenge your thinking; please challenge mine. The goal is not to win an argument but to learn. If I challenge a statement you make, I’m probing for deeper understanding. I’m not attacking you, I’m investigating our thoughts.

Some people are not comfortable with this type of conversation.

My mistake has often been in initiating this type of conversation without clarifying the rules of engagement. In the future, if everyone knows what I mean by robust discussion I might begin by saying, “Let’s have robust discussion about a particular topic.” If someone is unfamiliar with the term, I could say: “I’d like to talk about a particular topic with you. I have some solid ideas and opinions about it, but want to explore other sides to the issue. I value your thoughts and input. I need a sounding board. Please speak openly and so will I.”

Scenario 3—Let’s debate.

In this setting, we’ll take opposite sides of an issue and each of us will try to prevail. We both think we’re right so we’ll try to prove each other wrong. Neither of us will probably change our mind as a result of the conversation, though we might walk away with some doubts about our position.

There’s a proper time and place for each type of conversation.

Scenario 1 conversations are casual, courteous, and help develop relationships.

Scenario 2 conversations are intentional and focused, and promote clarity and learning.

Scenario 3 conversations are typically inappropriate for informal conversations. When debate is desired, it should be formally set up and regulated.

In my weekly blog posts, I’m obviously expressing my personal opinion. But I truly value and enjoy having robust discussion about the issues I proffer. So please hit the comment button and tell me what you think.