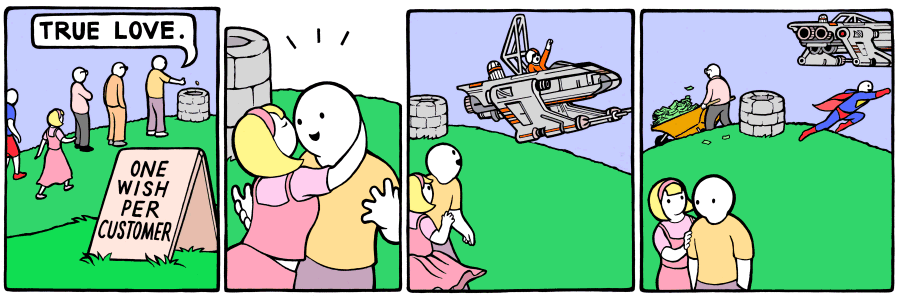

Counterfactual thinking (CFT) is a concept in psychology that involves the human tendency to create possible alternatives to life events that have already occurred; to consider something that is contrary to what actually happened. It is a hypothetical, fictitious perspective on the past.

CFT uses phrases like “what if” and “if only.”

-

-

- If only I had buckled my seatbelt before the accident.

- When aimed at President Kennedy, what if Lee Harvey Oswald’s gun had misfired?

- What if we had gone elsewhere on our vacation? We would have avoided the storm.

-

- CFT can be both positive and negative. Better alternatives are called upward counterfactuals; worse alternatives are downward counterfactuals. When reflecting on an incident, it can be played out for better or for worse. For example, a driver who causes a minor car accident might think: “If only I had swerved sooner, I could have avoided the accident.” In contrast, downward counterfactuals spell out the way a situation might have turned out worse; that is, the same driver could think: “If I had been driving faster, I might now be dead.”

Consider the emotions associated with CFT.

-

-

- Guilt — I feel guilty about neglecting my children when they were young; if only I had spent more time with them.

- Regret — If only I had chosen a different career path.

- Pity — If I hadn’t married so young, my life would have been better.

- Resentment — What if my son had not been arresrted; things would be so different.

- Anger and bitterness — If I had ignored my friend’s advice—buy an expensive car—I wouldn’t be in debt.

- Hope — By analyzing my mistakes, I have learned from them and will be a wiser person.

- Gratitude — Think what could have happened if my car had not been equipped with airbags.

- Insight — If only I had studied more, I would have passed the exam.

-

I love facts—things that are indisputable—so I initially resisted CFT because counterfactual literally means contrary to the facts. What possible benefit can be derived from reimagining history? It is as it was. But CFT can be beneficial. It can:

-

-

- Improve planning and goal-setting. “Let’s analyze our recent event and think about how we could have done it better.”

- Help us learn, grow, and assess our behaviors. “If I could have that conversation again, I would change what I said.”

- Give us hope. “I made a mistake, but I’ll not make that same mistake again.”

- Boost creativity. “Let’s explore all the ways we could have handled that differently.”

- Help create different paths for the future. “Let’s change our strategy.”

- Make us more proactive. “If I had been more involved, I could have influenced the outcome. Next time, I’ll be more aggressive.”

-

Know when to stop a particular episode of CFT. There is nothing wrong with taking time to ponder or reflect upon past events, but it’s important to let them go at the right time. If you continue to linger on and develop a particular counterfactual story, it can morph into a fantasy—an “alternative life”—a make-believe world that is disconnected from reality.

CFT should not be confused with embracing untruth—a claim, hypothesis, or belief that is contrary to the facts. We should never deny what actually happened. We can’t recreate history.

Like many other things in life, CFT has its advantages and disadvantages.

Here’s a good article on counterfactual thinking — https://psychology.iresearchnet.com/social-psychology/social-cognition/counterfactual-thinking/