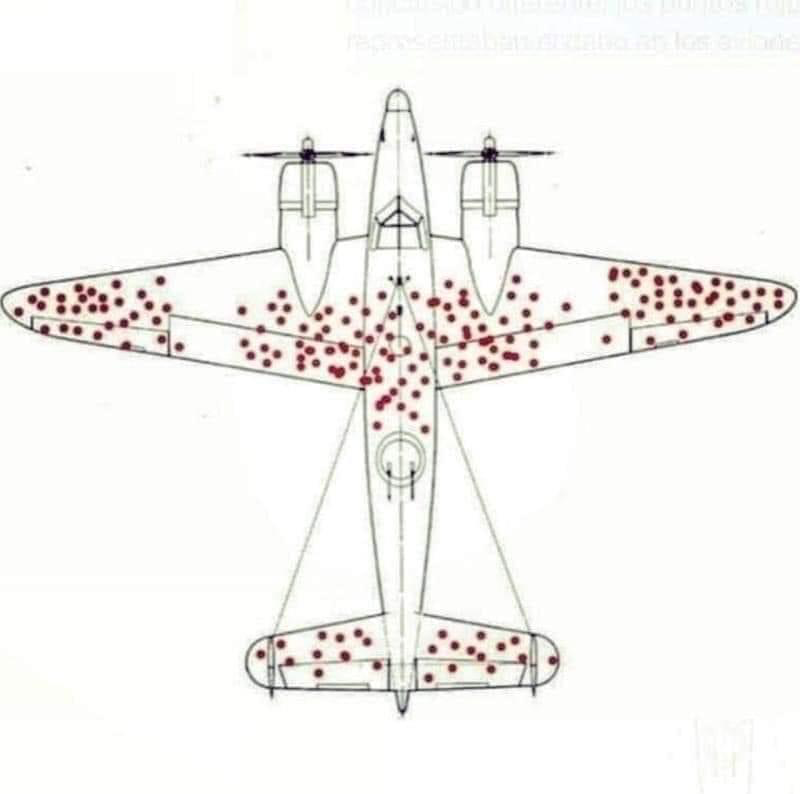

During World War II, the American military asked mathematician Abraham Wald to study how best to protect airplanes from being shot down. The military knew adding extra armor would help, but adding thick metal to the entire plane would make it too heavy to fly. Initially, their plan was to examine the planes returning from combat, see where they were hit the worst – the wings, around the tail gunner and down the centre of the body – and then reinforce those areas. They concluded that since planes coming home from battle have bullet holes everywhere but the engine and cockpit, it would be best to put armor everywhere except the engine and cockpit.

“But Wald realized they had fallen prey to survivorship bias because their analysis was missing a critical element: the planes that were hit but didn’t made it back. As a result, the military was planning to reinforce precisely the wrong parts of the planes. The bullet holes they were looking at actually indicated the areas a plane could be hit and keep flying – exactly the areas that didn’t need reinforcing.” [From BBC article]

This phenomenon is called survivorship bias. It happens when we only consider things that have survived or been successful and ignore those that have not. It is the logical error of focusing on successful people, businesses, or strategies and ignoring those that failed. We are tempted to think most success is due to particular characteristics that can be easily emulated.

Survivorship bias tends to distort data in only one direction, by making the results seem better than they actually are, which can lead to false conclusions and bad decisions.

Here are some more examples.

- In its advertising, a gym might feature clients who’ve toned up quickly as a result of going to their facility but, of course, they never show those who signed up but had little or no results.

- We often admire and are tempted to emulate people who have “beaten the odds.” For instance, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Michael Dell all dropped out of college but eventually became billionaires. Before following their example, students should consider the millions of students who dropped out of college but never got ahead in life (data shows that most college graduates eventually have higher income and better positions).

- In the world of investing, survivorship bias is very prevalent. Poorly performing funds are often closed down so they’re not represented in the data and significantly distort performance figures.

To avoid survivorship bias, simply ask this question: Are we only considering examples that represent success or does the data also include instances in which the system failed? For instance, consider the three examples from the previous paragraph. It’s obvious that only one side of the story is being considered. So analyze the data sources and don’t be misled.

Here’s a must-read article

Conversations are the life-blood of relationships. Lucy Folks wrote an insightful article titled How To Have More Meaningful Conversations. In the article, you’ll be able to download Arthur Aron’s 36 questions that lead to deeper relationships.