The important thing is not to stop questioning… Never lose a holy curiosity. Albert Einstein

I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who. Kipling

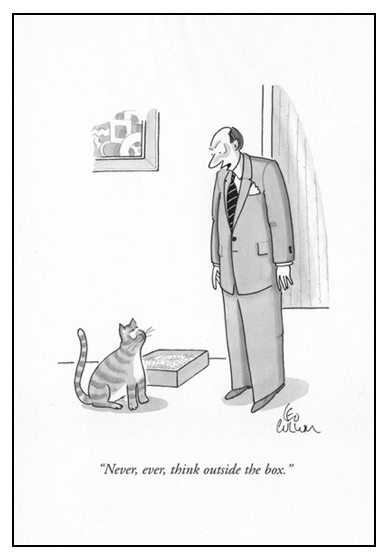

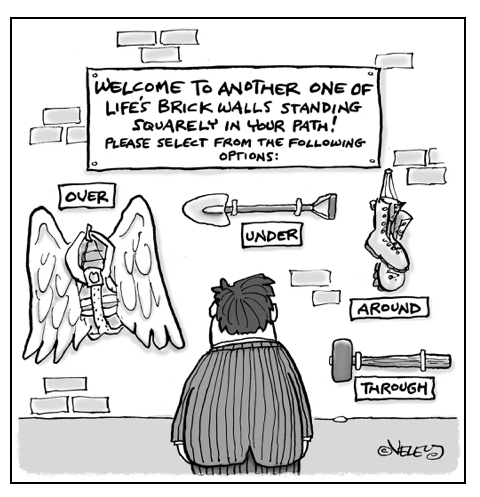

Curiosity is simply a strong desire to know or learn something. It is a wonderful trait. It is the antidote for a passive mind; it takes you to new places; it adds zest to life; it is the key to learning. I can’t think of any downsides.

Brian Grazer is the poster child for curiosity.

In his must-read book, A Curious Mind: The Secret to a Bigger Life, Grazer delves into the value of being curious. He dedicates the book, “For my Grandma Sonia Schwartz. Starting when I was a boy, she treated every question I asked as valuable. She taught me to think of myself as curious, a gift that has served me every day of my life.” What a great grandmother.

Early in life Grazer (who is a Hollywood movie producer) channeled his curiosity toward what he calls “curiosity conversations.” He contacts interesting people, requests a meeting, and if it happens, spends the time asking them questions. He’s had conversations with Muhammad Ali, Jeff Bezos, Jay Z, Steve Jobs, Condoleezza Rice, Ted Turner, Andy Warhol, Oprah Winfrey, and hundreds of other well-known people. What a wonderful expression of a curious mind.

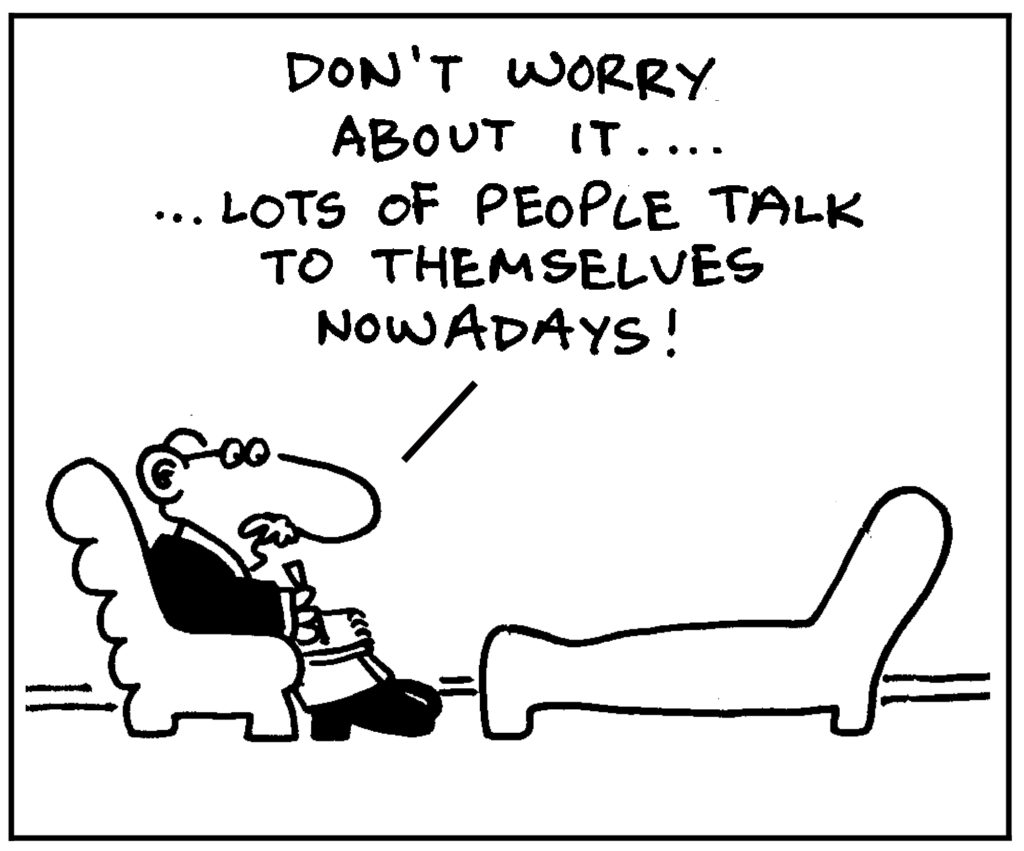

The sixty-four-dollar question is: are you curious? Here’s a short self-assessment.

- Name three things that you are currently curious about and actively pursuing.

- What have you changed your mind about, lately?

- What have you learned, lately?

“CQ stands for curiosity quotient and concerns having a hungry mind. People with a higher CQ are more inquisitive and open to new experiences. They find novelty exciting and are quickly bored with routine. They tend to generate many original ideas and are counter-conformist.” Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

Samuel Johnson said, “Curiosity is, in great and generous minds, the first passion and the last.”

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

A good half of the art of living is resilience. ― Alain de Botton

A good half of the art of living is resilience. ― Alain de Botton