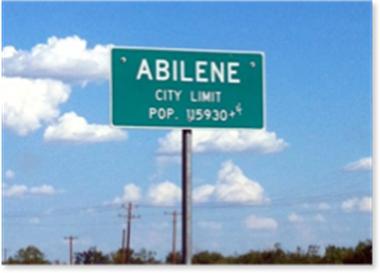

The term Abilene Paradox was introduced by management expert Jerry B. Harvey in his article The Abilene Paradox: The Management of Agreement.

The paradox refers to a situation in which a group of people collectively decide on a course of action that is counter to the preferences of many individuals in the group. Here’s the story Harvey tells in his article to illustrate this phenomenon.

On a hot afternoon in Coleman, Texas, a family (husband, wife, daughter, and son-in-law) is enjoying a comfortable afternoon at home when the father suggests that they take a trip to Abilene (53 miles away) for dinner. The daughter says, “Sounds like a great idea.” The son-in-law, despite having reservations about the trip (the drive is long and hot), thinks that his preferences must be out-of-step with the group, so he says, “Sounds good to me; does your mother want to go?” The mother says, “Of course I want to go. I haven’t been to Abilene in a long time.”

The drive is hot, dusty, and long. The food at the restaurant is as bad as the drive. They arrive back home four hours later, exhausted and frustrated.

One of them dishonestly says, “It was a great trip, wasn’t it?” The mother says that, actually, she would have preferred to stay home, but went along since the other three were so enthusiastic. The son-in-law says, “I didn’t want to go but I thought everyone else wanted to.” The daughter confesses, “I just went along to keep everybody happy.” The father, who initiated the trip, then admits that he only suggested it because he thought the others might be bored.

The group is perplexed that they took a trip which none of them wanted. How did that happen?

Several years ago my family planned on “enjoying” the July 4th weekend by going to a public pool, slather on sunblock, lie out in 100 degree heat and sun, and sweat. Driving to our destination, my son-in-law had the emotional fortitude to say, “I really don’t enjoy doing that.” Following a moment of reflection, it occurred to me that neither do I. My wife volunteered, “I don’t like getting in the sun because I don’t want to get skin cancer.”

We were “on our way to Abilene.” I’m not sure who initially suggested the outing or why (perhaps one of us noticed that famous people seem to do it often so it must be fun), but after we honestly discussed the idea it was aborted.

The Abilene Paradox can be avoided. When a group is making a decision, each group member should be asked, “What are your true and unfiltered thoughts about this issue?” Or, if everyone is familiar with the term, just ask, “Are we taking a trip to Abilene?”

Steven Wolff, with GEI Partners, says, “To harvest the collective wisdom of a group, you need two things: mindful presence and a sense of safety.” He explains that mindful presence is “being aware of what’s going on and inquiring into it. A sense of safety ensures that if I express my candid thoughts, I won’t be sanctioned.”

At work and at home, avoid the false sense of unanimity that can occur when an idea goes unchallenged. If no one pushes back on an idea or decision, you might be on your way to Abilene.