For the last 14 months of its life, the check engine light in my old Subaru Forester (230,000 miles) was constantly on. I would fix one issue that triggered the alarm and then another would flare up. I became so weary of the issue that I didn’t even want to have it checked out. I just ignored the light and would have disconnected it had I known how to.

Years ago (before Mary and I vowed to live debt-free) when our credit card bill would get out of hand, I avoided checking the balance because I knew it was high and out of control.

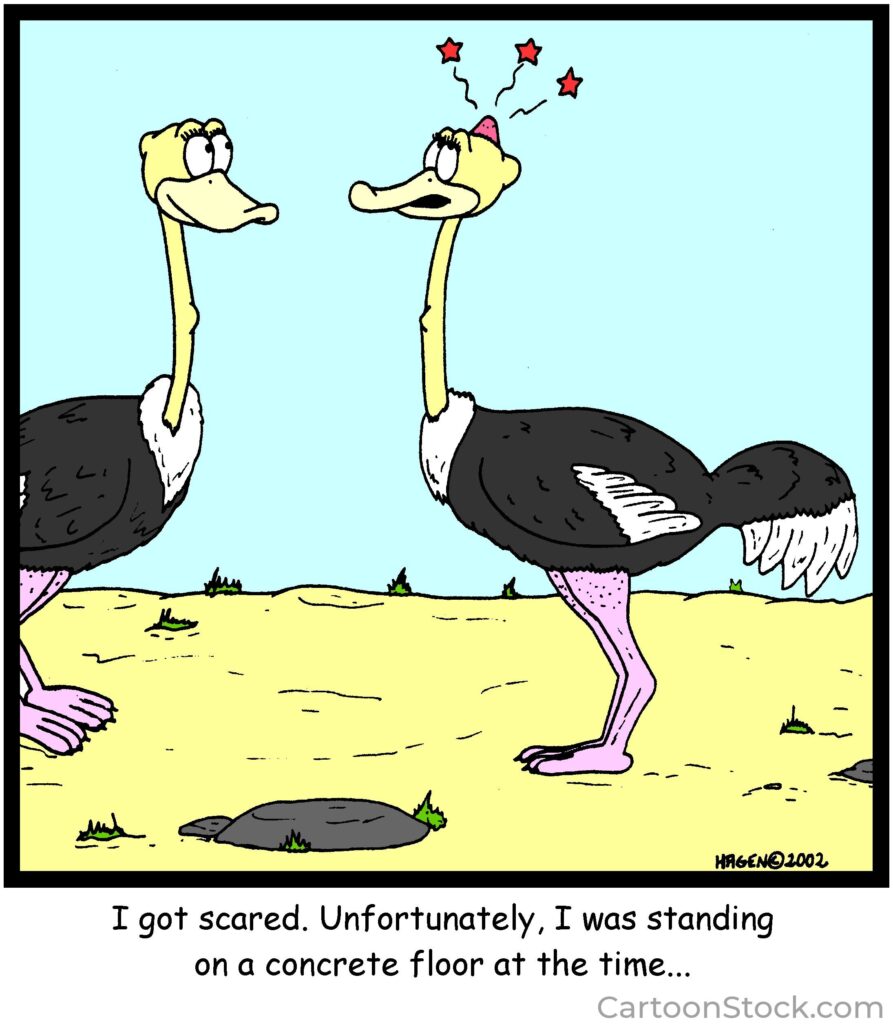

In both cases, I was exhibiting the ostrich effect (OE).

According to a persistent myth, ostriches bury their heads in the sand when they’re scared or feel threatened. They think they are safe if they can’t see the danger. (They don’t really do that.)

The ostrich effect is a cognitive bias that causes people to avoid information that they perceive as potentially unpleasant. From a psychological standpoint, OE is the result of the conflict between what our rational mind knows to be important and what our emotional mind anticipates will be painful. Instead of helping, it drains us of time, energy, and resources and offers nothing of value in return.

Here are some examples of the ostrich effect

- You may avoid getting a professional medical diagnosis because you’re afraid of hearing bad news (although, ironically, health information is crucial for health maintenance).

- You regularly check your retirement fund when the market is going up but not when it’s going down (although, to manage your money wisely, you need consistent data).

- Parents may hesitate to have a child who is having trouble in school tested.

- A business executive may postpone delving into what may be problems in the organization.

As is often the case with cognitive biases, the first step towards clarity is self-awareness. We must realize and admit that we’re falling prey to unhealthy thinking. I think the ostrich effect is one of the easiest biases to recognize: Just identify areas in your life in which you’re procrastinating or reluctant to get information because you think it might be bad news.

The antidote to the ostrich effect is also simple and straightforward: Immediately pursue areas that you’re avoiding and pursue them aggressively. Put them at the top of your to-do-list; pledge that you’ll not eat again until you address the issues.

The ostrich effect offers no value—there’s no upside—but overcoming it is very beneficial. As the Bible says, “The truth will set you free,” even if the truth is unpalatable.