In religious art, saints are often portrayed with halos, and the devil and demons have horns. Through the years, these contrived images have worked: when we see a halo, bathed in heavenly light, we think that the figure is good and pious; horns suggest the opposite.

Psychologists use these two symbols to illustrate an interesting phenomenon we often fall prey too. The halo and horn effects are cognitive biases that cause us to allow one trait, either good (halo) or bad (horn), to overshadow other traits, behaviors, actions, or beliefs.

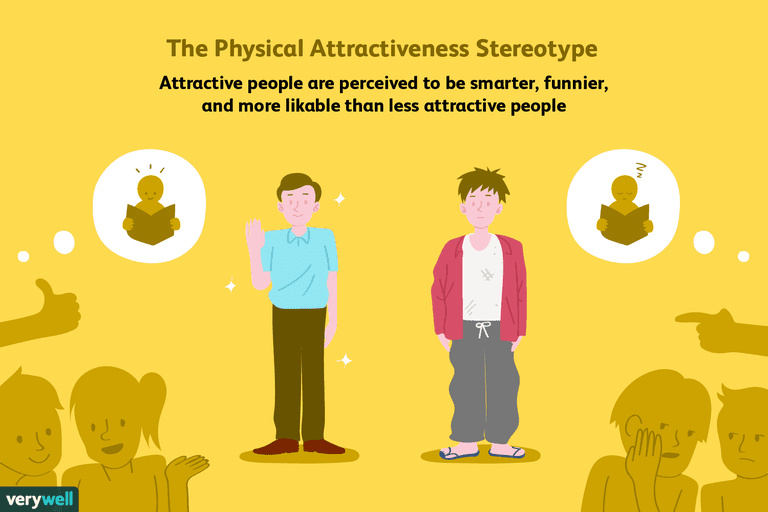

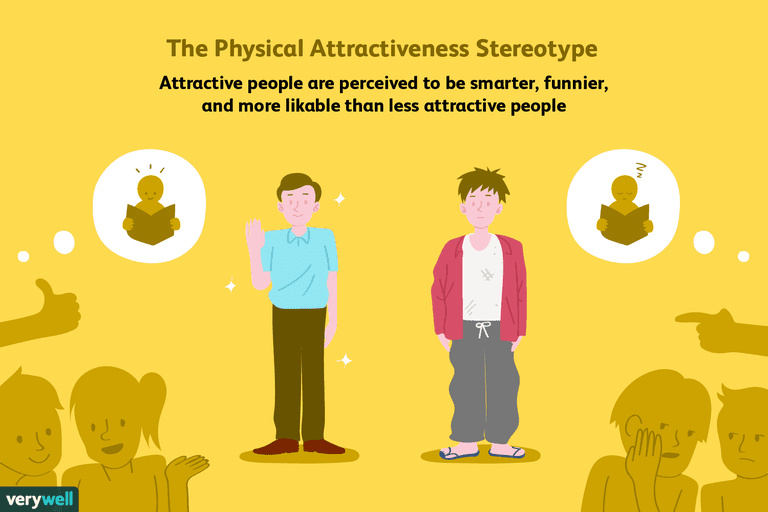

We tend to create an overall impression of someone or something based on one, unrelated trait. This bias can cause us to think too highly of someone or something (halo effect) and cause us to think poorly of someone or something (horn effect) because of a single characteristic or trait.

The halo and horn effects bias our assessment of people.

- We may assume (wrongly) that physically attractive people are more informed, intelligent, or competent.

- We may think someone who is disheveled and untidy is struggling in life and lacks acumen.

- We may think someone with a complicated-sounding name—Stephan Lewandowski—is more debonair than someone named John Smith.

- Someone who is winsome and engaging may be thought to be insightful or competent.

- One research study found that jurors were less likely to believe that attractive people were guilty of criminal behavior.

The halo and horn effects will prejudice our thinking in other areas of life.

- A car dealer will place its fanciest car in the middle of the showroom (fully realizing that the average buyer cannot afford it) because it enhances what customers think of the other models.

- A restaurant will list a $900 bottle of 2014 Penfolds Grange wine on their menu, (knowing that no one will probably buy it) because having it on the list makes customers think more highly of the entire restaurant. (I often wonder, do they even have a bottle of that wine? Perhaps they did, and sold it, but continue to list it.)

- A law firm will maintain high-dollar offices to perpetuate the appearance of success and expertise. (I wonder who is paying for those fancy offices. Hint: you, the client.) I thought we paid attorneys for their wisdom and experience, so why be swayed by mahogany desks on the 20th floor of a downtown office building?

- When consumers have an unfavorable experience, they may allow that one negative experience to influence what they think of the entire brand. (When eating at a restaurant, if the bathroom needs servicing, I may unfairly dismiss the entire restaurant even though all other factors are good.)

How can we guard against these unproductive and misleading tendencies?

- Think holistically. A comprehensive approach recognizes that there are many parts to a whole entity and that the whole should not be judged on one part. One characteristic cannot adequately or fairly define an entire entity.

- Be skeptical of advertising and marketing because they often intentionally use the halo effect to promote a product and the horn effect to demean the competition.

Action item — Identify situations in which you have been tricked by the halo and horn effects.

Discussion question — How can we develop an immunity to these two biases?