A placebo, most often used in drug studies, is used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of treatments. For instance, people in one group get the drug being tested, while the control group receive a fake drug, or placebo, that they think is the real thing. This way, the researchers can measure if the drug truly works by comparing how both groups react. If they both have the same reaction — improvement or not — the drug is deemed ineffective. [Harvard Health Publications, May, 2017]

A placebo, most often used in drug studies, is used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of treatments. For instance, people in one group get the drug being tested, while the control group receive a fake drug, or placebo, that they think is the real thing. This way, the researchers can measure if the drug truly works by comparing how both groups react. If they both have the same reaction — improvement or not — the drug is deemed ineffective. [Harvard Health Publications, May, 2017]

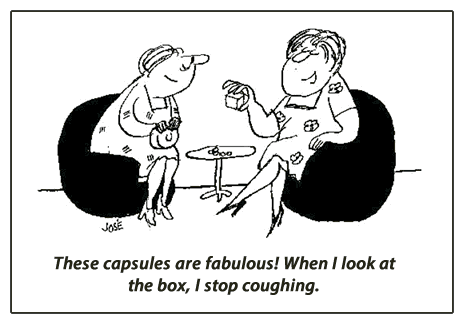

A familiar example is putting a Band-Aid on a child. It can make the child feel better though there is no medical reason it should. Patients suffering from depression have reported that they feel better after taking a new anti-depressant though all they ingested was an inert substance.

This is well-known information.

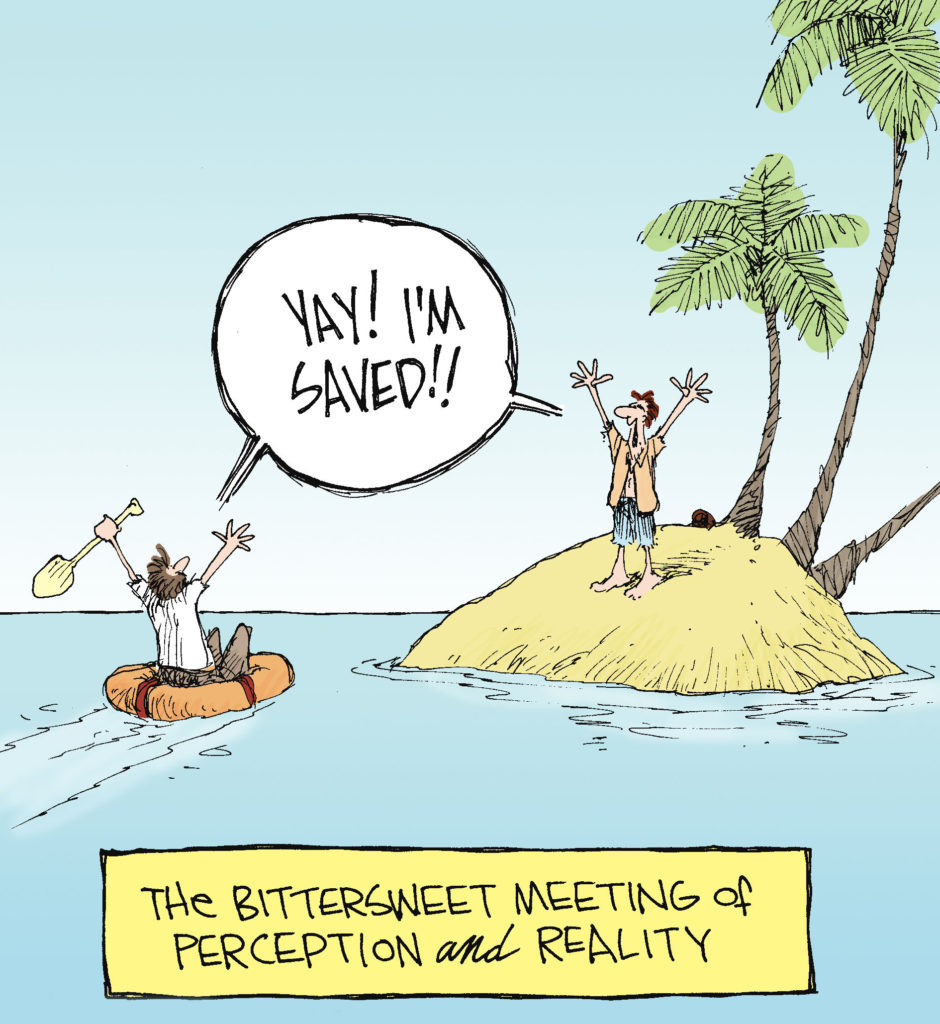

But here’s some recent information that takes this conversation to a new level.

A recent study conducted by the Harvard Medical School suggests that deception may not be necessary for the placebo effect to occur; a placebo may work its magic even when people know they are taking a pill filled with nothing but a saline solution.

For instance, a writer went to see his physician because he was having panic attacks which then caused writer’s block. The doctor gave him a bottle of pills marked “placebo” and even told the patient that the pills contained no drugs, but to take two pills when he started feeling anxious. It worked.

What are we to make of this? Are we humans inordinately and pathetically subject to our psyche? Is it manipulative to offer humans a placebo type solution?

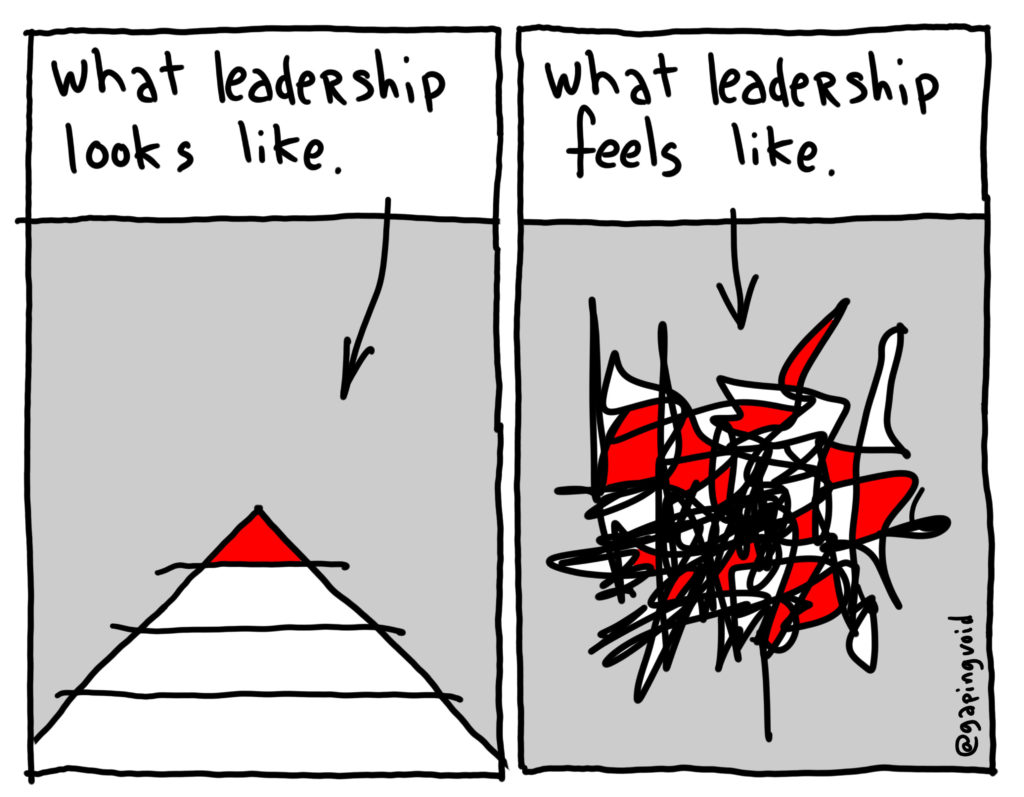

It is a deep subject for my shallow mind, but here are my thoughts.

Perhaps you can give yourself a placebo by engaging in known and verified self-help methods. Eat right, exercise, meditate, spend quality time with healthy people, pray—these actions will help you mentally, emotionally and physically, perhaps even beyond their obvious and true benefit.

When others are hurting or distressed, offer emotional support and physical companionship. Play the part of the “Band-Aid.” Or, give them a multivitamin and tell them it’s a rare drug recently approved by the FDA (just kidding).

Readers, I could use your help on this topic. What do you think?

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

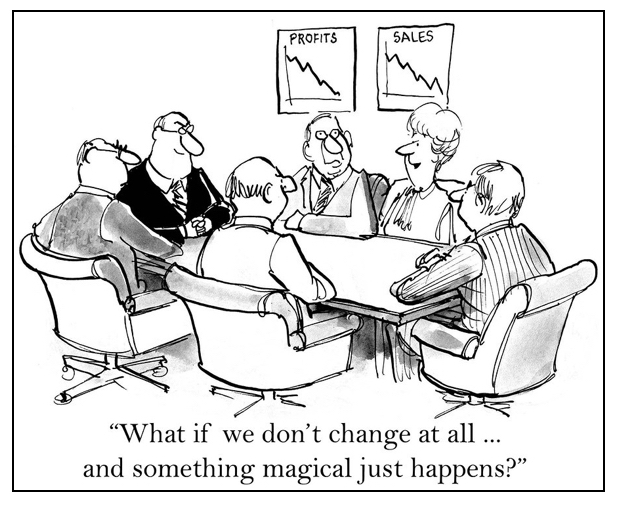

One of the most encouraging things about life is that at any time we can decide to change and chart a new course. Life is like a book with many chapters; as the author, you can start a new chapter at anytime.

One of the most encouraging things about life is that at any time we can decide to change and chart a new course. Life is like a book with many chapters; as the author, you can start a new chapter at anytime.