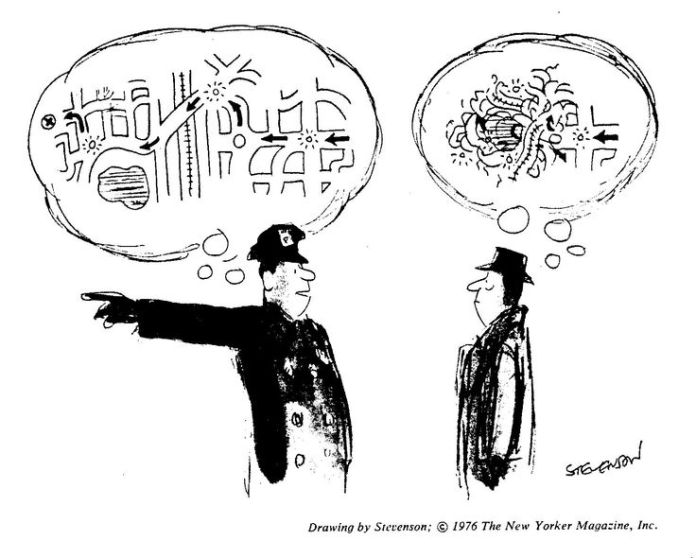

I’ve been thinking about how to honestly and appropriately respond to conversations in which I disagree with what is being said.

For instance,

-

-

- I was talking with a friend who veered off into a controversial political issue. I guess he just assumed I agreed with his convictions on the topic, but I didn’t. Should I have jumped into the fray? If I don’t say something, he might assume my silence means I concur with his thoughts. But pushing back might lead to an argument.

- I was part of a conversation in which someone energetically shared about a certain topic, but her facts were wrong. Should I have corrected her?

-

In these and many other conversational situations, I’m trying to discipline myself to respond appropriately. There are several options.

-

-

- Sometimes I need to speak up and challenge what is being said, even if it leads to an uncomfortable conversation. I must be kind and tactful with my pushback but I should be straightforward in sharing my thoughts, even if it may produce an uneasiness or even tension.

- At other times I should simply not respond. Sensing the larger purpose of the conversation, I might realize that the comments being made are not central to the overall thrust and direction of the conversation. Or, I may value the relationships of those involved so much that I should not push back because doing so might sully the relationships.

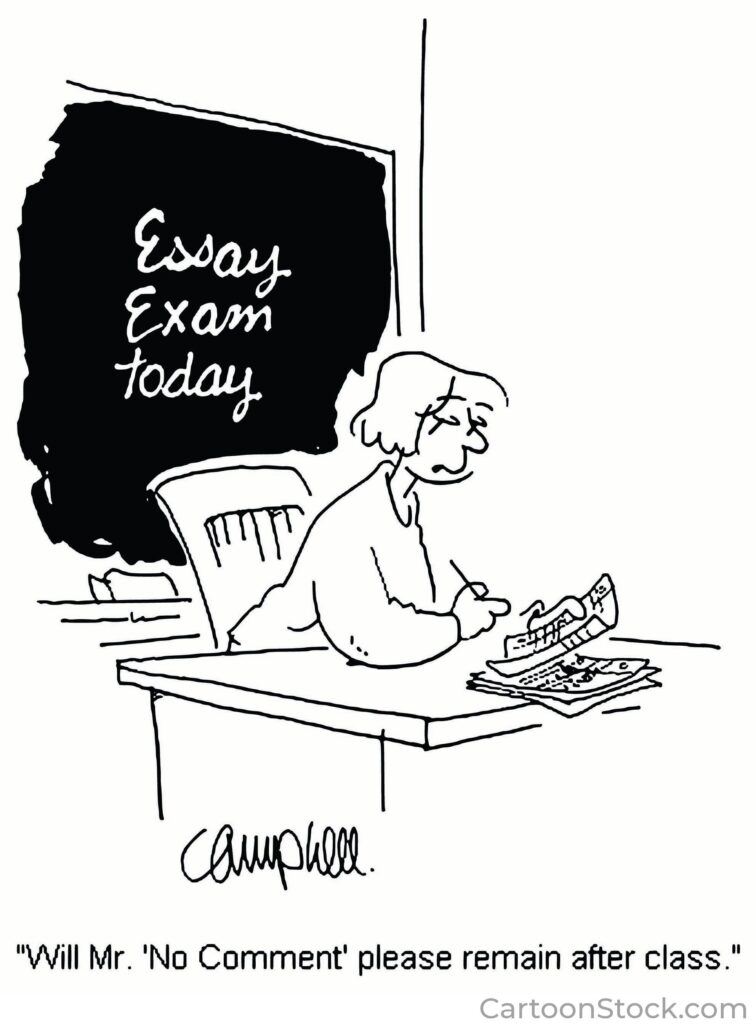

- Or, (and here’s the trust of this post) I can say “No comment.”

-

“No comment” can mean several different things:

-

-

- I don’t agree with what’s being said but I don’t want to get embroiled in a lengthy, potentially combative conversation.

- I don’t have an opinion about the particular subject or scenario.

- I don’t have time to pursue this topic right now.

- For whatever reason, I want to stop this part of the conversation.

- I do have a lot to say, but I don’t want to offend you.

-

So by saying “no comment” I’m actually commenting.

What are your comments? (respond below)