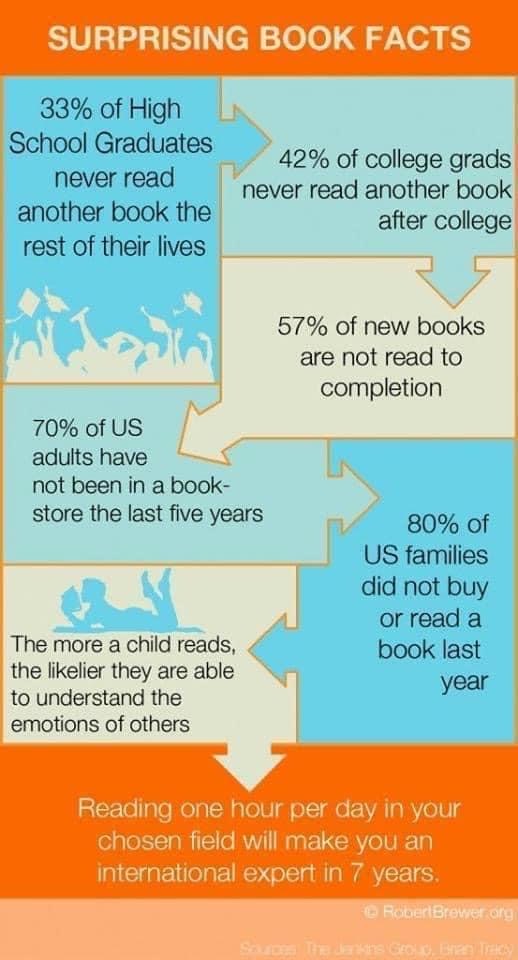

My grandson, Benjamin (seven years old), learned how to read this year. I am so happy for him because he now has access to the world’s knowledge. He can learn anything he wants to. I hope he will be a lifelong lover of books. (I’ve bequeathed my library to him.)

If you’re not a reader, make that your number one goal for 2022. Reading just one good book a month will change your life.

Here are the books I read in 2021. The numbers in brackets represent how I rate each book on a scale from 1 (not good) to 10 (exceptional).

January

- The Billionaire’s Vinegar – The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine – Benjamin Wallace, 2008, 323 pages [8] – On December 5, 1985, a bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite Bordeux—allegedly owned by Thomas Jefferson—sold for $156,000 at Christy’s auction house. But was it a fraud? This is a fascination read, even if you don’t enjoy wine.

- Fault lines – The social justice movement and evangelicalism’s looming catastrophe – Voddie Baucham, 2021, 249 pages [5] – Baucham makes an unusual argument regarding the social tensions felt in our society.

- Thomas Jefferson – Author of America – Christopher Hitchens, 2005, 188 pages [8] – A good, relatively short biography of the great man.

February

- Intelligent Thinking – Som Bathla – date unknown, 163 pages [6] – I’ve never seen a book with this many typos. It’s self-published and it shows. However, there are a few good nuggets scattered throughout.

- Call Sign Chaos – Learning to Lead – Jim Mattis – 2019, 249 pages [8] – General Mattis is an American hero. He speaks well on leadership because he’s done it well. Just the final chapter – Reflections – is worth the price of the book.

- Muhammad – A Profit for Our Time – Karen Armstrong – 2006, 202 pages [7] – Armstrong, a well-respected authority on world religions, writes about Muhammad, the founder of the world’s second largest religion. An interesting read, though I am skeptical when an historian writes with confidence something like, “For three years, Muhammad kept a low profile, preaching only to a selected people, but somewhat to his dismay, in 615 Allah instructed him to deliver this message to the whole clan of Hashim.” This happened 1,500 years ago; how does Armstrong (or anyone) know such specifics?

March

- The God Equation – Michio Kaku – 2021, 210 pages [8] – Einstein solidified the General and Specific theories of relativity; many physicists have contributed to the theory of quantum mechanics. Now physicists are working on the unified theory – a theory that will unify and explain all physical properties of the universe. Kaku gives a brief history of what physicists have worked on and accomplished from the time of Isaac Newton to modern day. This is a great and accessible read.

April

- The Best of P.G.Wodehouse – An Anthology – [6] – Wodehouse (1881-1975) was perhaps the most widely acclaimed British humorist of the twentieth century. His writing is brilliant, but I lost patience and cherry-picked what I read.

- Fundamentals – Ten Keys to Reality – Frank Wilczek – 2021, 241 pages [7] – As a graduate student, Wilczek won the Nobel Prize in physics in 2004. He’s now a professor at MIT. In an accessible way, he discusses the fundamentals of the universe: time, space, matter, energy, complexity and complementarity.

May

- Think Again – The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know – Adam Grant – 2021, 257 pages [9] – Terrific book in which Grant examines the critical art of rethinking: learning to question your opinions and open other people’s minds.

- Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain – Lisa Barrett – 2020, 166 pages [9] – Scientists have learned a lot about the brain in the past 20 years. Barrett brings us up to date. Her style is accessible and engaging. I appreciate when brilliant people communicate in a way that lay-persons can understand.

June

- The Bomber Mafia – Malcolm Gladwell – 2021, 206 pages [8] – In WW2 there were two approaches to bombing the enemy: precision bombing of facilities critical to a country’s war effort (factories, utilities, transportation) or indiscriminate bombing of entire cities. This book tells the story of both approaches.

- A Gentleman in Moscow – Amor Towles – 2016, 462 pages [9] – A Russian aristocrat is put on house arrest in the Metropol hotel in Moscow, never to leave the hotel. The story starts in 1922 and ends in 1954. A wonderful novel.

- Who Not How – Dan Sullivan – 2020, 172 pages [concept – 8; book – 5] – I wish I had internalized this thought when I was beginning my career: When something needs to get done, don’t ask how can this be done, ask who can to it. Learn to delegate work to people who already know how to do it. The thought is great, the book is not. I’ll write a post on the principle and save you having to buy the book.

July

- On Bullshit – Harry Frankfurt – 2005, 67 pages [6] – An essay written by Frankfurt – a professor of philosophy at Princeton University. He takes a deep dive into the etymology of this word. Fascinating approach, but little practical application.

- The Secret Life of Books – 2019, 212 pages [8.5] – A fascinating tome on the world of books. The history of books, how they’re made, libraries, etc. If you love books, you will enjoy this one.

August

- Rules of Civility – Amor Towles – 2011, 324 pages [8] – Towles first novel, the story is attractive and his prose is engaging.

- A Sense of Urgency – John Kotter – 2008, 194 pages [5] – I enjoyed Kotter’s book, Leading Change, but this book is not worth the read. It’s basically an expansion of chapter 1 of Leading Change. This book should have been an article.

- Cleopatra – Stacy Schiff – 2010, 326 pages [8] – An incredible biography on one of the most intriguing women in history. Schiff is a good historian that writes terrific books.

- Winnie the Pooh on Management – Roger Allen – 1994, 161 pages [5] – Because of the extended illustration, it took too much effort to get to the management principles.

September

- The Golden Moments of Paris – John Baxter – 2014, 269 pages [7] – Before my five-day trip to Paris in November, I read two books (this one and number 22) about the decade of the 1920’s in Paris. It was a memorable decade.

- When Paris Sizzled – Mary McAuliffe – 2016, 270 pages [8] – See above.

October

- The Culture Code – Daniel Coyle – 2018, 259 pages [9] – Helping and engaging thoughts on building good culture in an organization. My staff and I processed the book together.

- The Sentinel – Lee Child – 2020, 349 pages [6] – My least favorite Lee Childs book novel about Jack Reacher.

November

- What Would Keynes Do? How the greatest economists would solve your everyday problems – Tejvan Pettinger – 2018, 183 pages [7] – Interesting read on applying economic theory to daily life. It draws thoughts from many economists, not just Keynes.

- Galileo and the Science of Deniers – Mario Live – 2020, 269 pages [7] – Starting with Galileo, the author discusses the problem of science denial. denying science.

Five best books I read in 2021

The Culture Code – Daniel Coyle – 2018, 259 pages [9] – Helping and engaging thoughts on building good culture in an organization. My staff and I processed the book together. Coyle focuses on three main points: Build safety, share vulnerability, and establish purpose.

A Gentleman in Moscow – Amor Towles – 2016, 462 pages [9] – A Russian aristocrat is put on house arrest in the Metropol hotel in Moscow, never to leave the hotel. The story starts in 1922 and ends in 1954. A wonderful novel. It recently made the list of the 125 most important novels of the last 100 years.

Think Again – The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know – Adam Grant – 2021, 257 pages [9] – Terrific book in which Grant examines the critical art of rethinking: learning to question your opinions and open other people’s minds. His books are always engaging and approachable.

Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain – Lisa Barrett – 2020, 166 pages [9] – Scientists have learned a lot about the brain in the past 20 years. Barrett brings us up to date. Her style is accessible and engaging. I appreciate when brilliant people communicate in a way that lay-persons can understand.

Call Sign Chaos – Learning to Lead – Jim Mattis – 2019, 249 pages [8] – General Mattis is an American hero. He speaks well on leadership because he’s done it well. Just the final chapter – Reflections – is worth the price of the book.