In his terrific book, Precipice, Australian philosopher Toby Ord talks about existential risks that threaten the future of humanity. Some are natural risks: an asteroid hitting the earth, or super-volcanic eruptions. Another category is anthropogenic risks which are caused by humans, like nuclear weapons, climate change, and unaligned artificial intelligence.

But the risks that are most alarming to me are the risks that may develop that we currently can’t even imagine.

It’s happened before.

-

- The possibility of nuclear holocaust was inconceivable until 1942 (the year physicist Enrico Fermi initiated the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction).

- The field of artificial intelligence wasn’t formally founded until 1956, at a conference at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire, where the term was coined.

So 60 years ago, nuclear catastrophe and unaligned artificial intelligence would not have been mentioned in Ord’s book.

Chances are good that in the next 50 years, an existential threat will be identified that we have never even thought of.

Which leads me to a discussion of the end of history illusion.

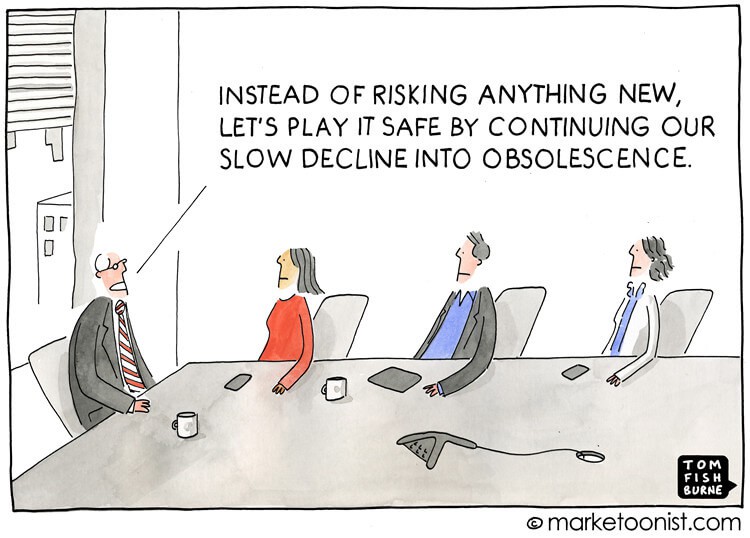

Humans have a tendency to acknowledge that change took place in the past but we discount the possibility of change happening in the future. For example, a 20-year-old’s prediction of how great a change he will undergo in the next ten years will not be as extreme as his recollection, as a 30-year-old, of the changes he underwent between the ages of 20 and 30. The same phenomenon is true for people of any age.

We can clearly see how our lives have changed a lot in the past, but we are reluctant to anticipate how much our lives will change in the future. Psychologist Dan Gilbert says we are “works in progress claiming to be finished.” In his research he discovered that young people, middle-aged people, and older people all believed they had changed a lot in the past but would change relatively little in the future. [Click here for more information about Gilbert’s work.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/End-of-history_illusion

We need to disavow ourselves of this illusion.

Relative to change:

Change is inevitable so we should anticipate and embrace it.

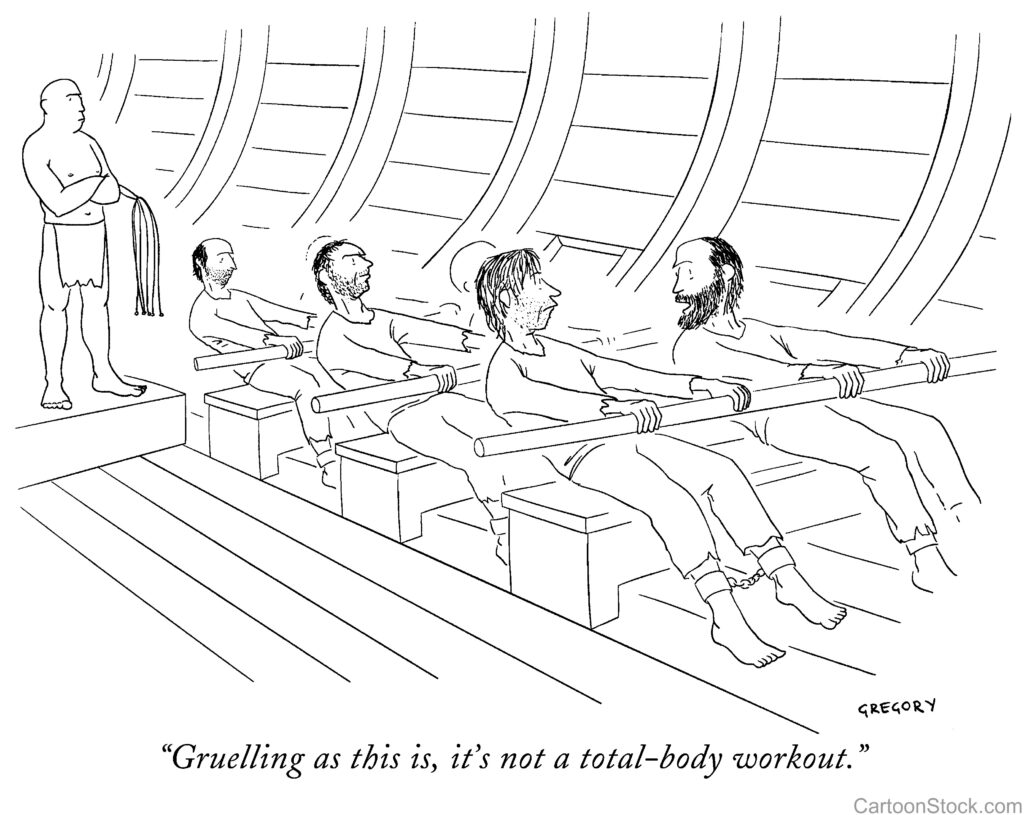

Every individual (and organization) has its own unique attitude toward change. We can be change-averse (resistant to change); we can reluctantly acquiesce to change (change is seen as unavoidable but undesirable) we can be change-friendly (view change as inevitable and probably necessary), or change-eager (view change as desirable and the key to growth and health).

The rate of change is going to accelerate.

In their must-read book, The Leader’s Voice, Clarke and Crossland say, “In ancient times, work was performed on an almost stationary stage. Visionary inventor Ray Kurzweil explains the rate of change in terms of paradigm shifts. During the agricultural age, paradigm shifts occurred over thousands of years. The industrial age produced paradigm shifts, first in a century and then in a generation. At the start of the information age, paradigms appeared to shift at the rate of three per lifetime. Kurzweil suggests that beginning in the year 2000, paradigm shifts have begun to occur at the rate of seven to ten per lifetime.”

Two thousand five hundred years ago the Greek philosopher Heraclitus said, “The only thing that doesn’t change is change.” Let’s anticipate and embrace changes that will occur in the future.