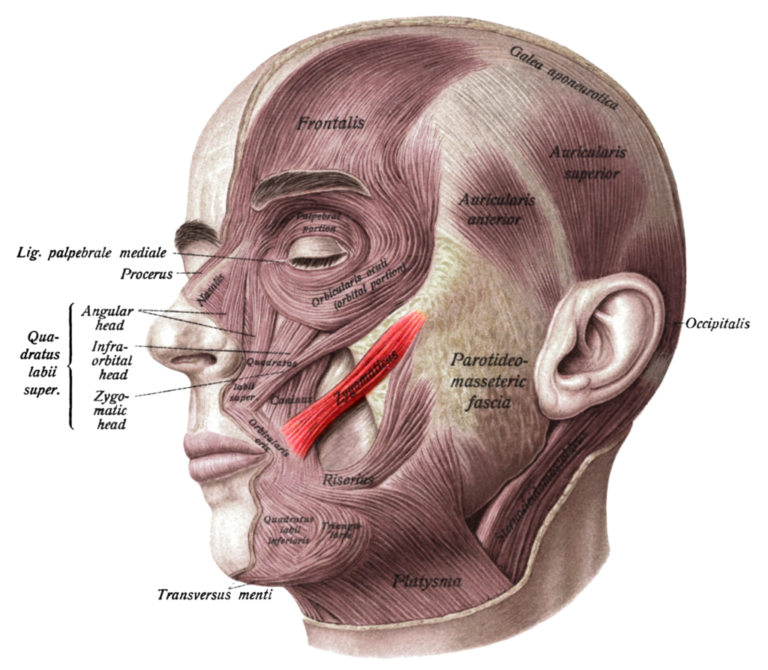

The human face has around 30 muscles on each side, depending on how they are counted. It takes 47 muscles to frown and only 13 to smile. The main muscle used in smiling is the zygomaticus major, also known as the smiling muscle.

The simplest, quickest, and easiest way to enhance your well-being in life is to exercise that muscle often. Train yourself to wear a perpetual smile.

Dale Carnegie’s terrific book, How to Win Friends and Influence People is a must-read. Though written almost 100 years ago (1926), it is so rooted in basic human psychology, it still speaks to our modern age.

He taught seminars based on his book to large audiences in New York City.

Carnegie devoted an entire chapter— A Simple Way to Make a Good First Impression— to the topic of smiling. When he taught this chapter at his seminars, he gave his students a simple assignment: Smile at someone every hour of the day for the next week and then come back to class and talk about the results. The positive results of this simple exercise were profound. His students learned that a smile is one of the most potent people skills and that it can dramatically improve human relationships.

Carnegie concluded his chapter on the power of a smile with these words:

The Value of a Smile

-

-

- It costs nothing, but creates much.

- It enriches those who receive, without impoverishing those who give.

- It happens in a flash and the memory of it sometimes lasts forever.

- None are so rich they can get along without it, and none so poor but are richer for its benefits.

- It creates happiness in the home, fosters good will in a business, and is the countersign of friends.

- It is rest to the weary, daylight to the discouraged, sunshine to the sad, and Nature’s best antidote for trouble.

- Yet it cannot be bought, begged, borrowed, or stolen, for it is something that is no earthly good to anybody till it is given away.

-

It’s helpful to consider the difference between our resting face and our engaged face.

Resting face – the way your face looks when you are at ease, with facial muscles relaxed.

Engaged face – the way your face looks when you are consciously manipulating your face to appear more engaged, approachable, and friendly. I’ve also heard this called a “yes face.”

To display an engaged face, raise the eyebrows, open up the eyes, smile, and raise the forehead. To exhibit a resting face, do nothing.

Let’s accept the same assignment Dale Carnegie challenged his students with: Put on you engaged face and smile at someone every hour of the day for the next week and then come back to class and talk about the results. Or, in our case, respond to this blog post.