Small wins have an influence disproportionate to the accomplishments of the victories themselves. Charles Duhigg

Small wins have an influence disproportionate to the accomplishments of the victories themselves. Charles Duhigg

It seems our brains aren’t very good at distinguishing big successes from small successes. Often, we’ll enjoy as much emotional and mental reward when we succeed at something simple as we do with large wins. So, in your life and organization, orchestrate a series of small wins to generate “success momentum”—the feeling you get when you succeed over and over.

For instance, if you know you’re going to have a challenging day, perform a series of small wins to build momentum and to increase confidence and resiliency. This strategy will combat procrastination and complacency, and will provide a growing sense of satisfaction and control.

If your organization is stalled or when you’re launching a new product or service, you can generate momentum by designing, accomplishing, and celebrating a series of small wins.

Here’s a great example of the benefit of small wins.

William H. McRaven, a retired U.S. Navy four-star admiral and former commander of the U.S. Special Operations Command, is now chancellor of the University of Texas System and leads one of the nation’s largest and most respected systems of higher education.

On May 17, 2014, McRaven delivered the commencement address at his alma mater, University of Texas at Austin. In his speech, he gave 10 suggestions on how to change the world. His first point was: make your bed.

“Every morning in basic SEAL training, my instructors, who at the time were all Vietnam veterans, would show up in my barracks room and the first thing they would inspect was your bed. If you did it right, the corners would be square, the covers pulled tight, the pillow centered just under the headboard and the extra blanket folded neatly at the foot of the rack—that’s Navy talk for bed.

It was a simple task, mundane at best. But every morning we were required to make our bed to perfection. It seemed a little ridiculous at the time, particularly in light of the fact that we were aspiring to be real warriors, tough battle-hardened SEALs, but the wisdom of this simple act has been proven to me many times over.

If you make your bed every morning, you will have accomplished the first task of the day. It will give you a small sense of pride and it will encourage you to do another task and another and another. By the end of the day, that one task completed will have turned into many tasks completed. Making your bed will also reinforce the fact that little things in life matter. If you can’t do the little things right, you will never do the big things right.

And if by chance you have a miserable day, you will come home to a bed that is made—that you made—and a made bed gives you encouragement that tomorrow will be better.”

Making your bed every morning is a simple example of how small wins can be used to generate momentum and can lead to larger accomplishments. Take advantage of the power of small wins.

Here’s a video of McRaven’s speech at U.T. Austin.

[youtube id=”yaQZFhrW0fU”]

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

Getting angry is okay as long as you get angry for the right reason with the right person to the right degree using the right words with the right tone of voice and appropriate language. Aristotle

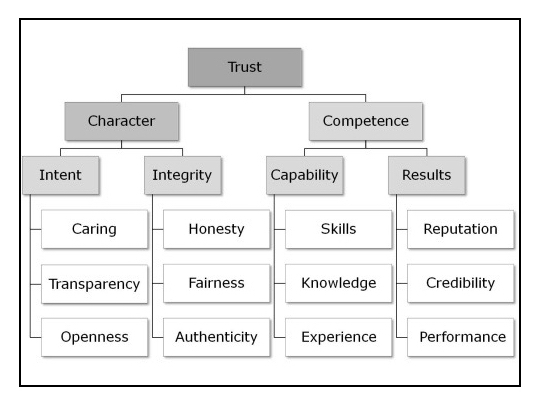

Getting angry is okay as long as you get angry for the right reason with the right person to the right degree using the right words with the right tone of voice and appropriate language. Aristotle Among all the attributes of the greatest leaders of our time, one stands above the rest: They are all highly trusted. You can have a compelling vision, rock-solid strategy, excellent communication skills, innovative insight, and a skilled team, but if people don’t trust you, you will never get the results you want. David Horsager

Among all the attributes of the greatest leaders of our time, one stands above the rest: They are all highly trusted. You can have a compelling vision, rock-solid strategy, excellent communication skills, innovative insight, and a skilled team, but if people don’t trust you, you will never get the results you want. David Horsager Imagine that you’re in a dark auditorium and suddenly a spotlight is turned on. It is bright and clearly illumines the area it shines on. But it is a limited area and someone is controlling where you are looking.

Imagine that you’re in a dark auditorium and suddenly a spotlight is turned on. It is bright and clearly illumines the area it shines on. But it is a limited area and someone is controlling where you are looking.