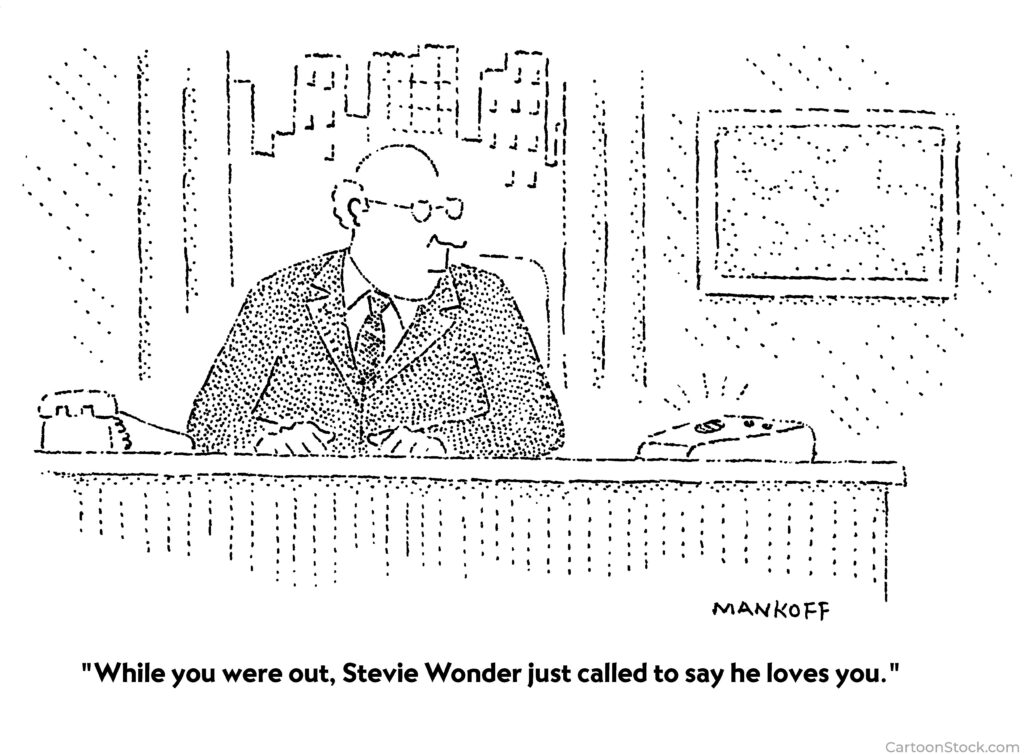

My church is having a four-week emphasis on Love like Jesus. On the first Sunday, Pastor Chuck began his exposition of 1 Corinthians 13 and in his message he encouraged everyone to speak often to those you care about, these three magical words: “I love you.”

Our nine-year-old grandson, Ben, was sitting with us in the service playing Hangman and Tic-tac-toe. I assumed he didn’t pay much attention to the sermon, but several times that evening he approached Mary and me and said, “I love you.” From the day he was born I have often affirmed my love for him by saying that phrase.

Our 7-month old granddaughter, Claire, and her mother live with us. Many times a day I tell her I love her. She doesn’t understand what I’m saying, though I suspect that she picks up on the tender emotions of the moment.

I’m wondering: why do I often say “I love you” to my grandchildren but don’t say it to adults. Other than to my wife, it’s been a long time since I’ve spoken these live-giving words to someone over the age of 10. Why is that?

I could blame it on my family of origin—I can’t remember my father ever speaking those words to me—but that’s a flimsy excuse. I could blame it on our culture—“real men” don’t do that, or on acceptable norms—it seems odd for adults to say that to one another—but the guiding principle should be: the Bible tells us to love one another and that should include verbally expressing our love to one another.

I’m going to change.