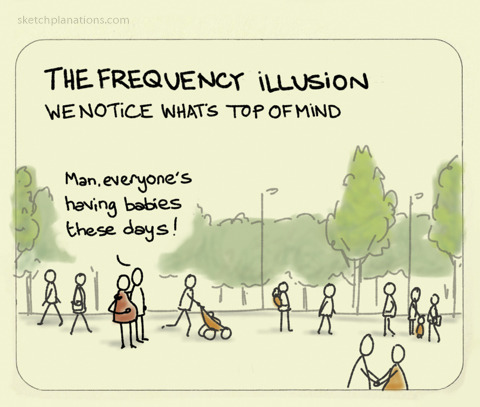

Years ago I was in the market to buy a new car. After researching different makes and models I narrowed my choice to a Subaru, a car I had previously never considered. Suddenly, I noticed Subarus everywhere.

For the first 69 years of my life, I never ate at Whataburger. But one day I overheard someone say that it was their favorite hamburger so I tried it out. It is a great meal. I’m sold. Suddenly, I saw Whataburger restaurants everywhere. I’ve been driving down to the family Lakehouse for the last five years and never noticed that there are four Whataburgers along the way. Of course, they were there all along; I’m just now seeing them.

There are several terms that describe this phenomenon; one is colloquial, coined by a journalist, and the other is a more academic phrase coined by a psychology professor.

The term Baader-Meinhof phenomenon was first used in 1994 by a commenter on the St. Paul Pioneer Press’ online discussion board, who came up with it after hearing, for the first time, the name of the ultra-left-wing German terrorist group twice in 24 hours. Once he was exposed to the name, he saw it often in various venues.

In 2006 Stanford professor Arnold Zwicky coined the phrase “frequency illusion” to describe this phenomenon. It’s caused, he wrote, by two psychological processes. The first, selective attention, kicks in when you’re struck by a new word, thing, or idea; after that, you subconsciously keep an eye out for it, and as a result find it surprisingly often. The second process, confirmation bias, reassures you that each sighting is further proof of your impression that the thing has gained sudden omnipresence.

We can use this phenomenon to our advantage. Since we tend to notice those things that are “top of mind” and overlook those that are not, let’s choose what we want to notice and pay attention to. For instance:

-

-

- We are surrounded by innumerable reasons to be grateful—life, freedom, friends—but we’ll remain unaware, and perhaps ungrateful, unless we look for them.

- We are encompassed by beauty—nature, children, music, books—but often don’t recognize it.

- God is at work in our lives but we may not recognize His activity because we’re looking elsewhere.

-

This concept has huge implications for goal setting. I’ve often wondered why, when we set a goal and go public with it, our chances of accomplishing the goal dramatically increase. The Baader-Meinhof phenomenon would suggest that once goals are placed in the forefront of our minds we’re more aware of them and we’ll devote more time and effort to achieving them.

For instance, several years ago I set a goal of making 50 new friends in a year. Having set and announced the goal, making friends become an important part of my conscious thinking. I constantly looked for potential friends and found them everywhere.

We can train our minds using this principle and prosper from it.

Plus – an article worth reading

If you have children or grandchildren, you need to read this article titled The No. 1 soft skill that predicts kids’ success more than IQ—and how to teach it .