We can’t control most things in life. We can’t control the weather, other people, our DNA, our family of origin, etc. But in most situations, there are things we can control that lead to health and happiness. We need to embrace and do those things.

I am impatient with people who are unhappy and think there are no solutions to their problems so they become passive; they do nothing. They refuse to do even simple things that could improve their life.

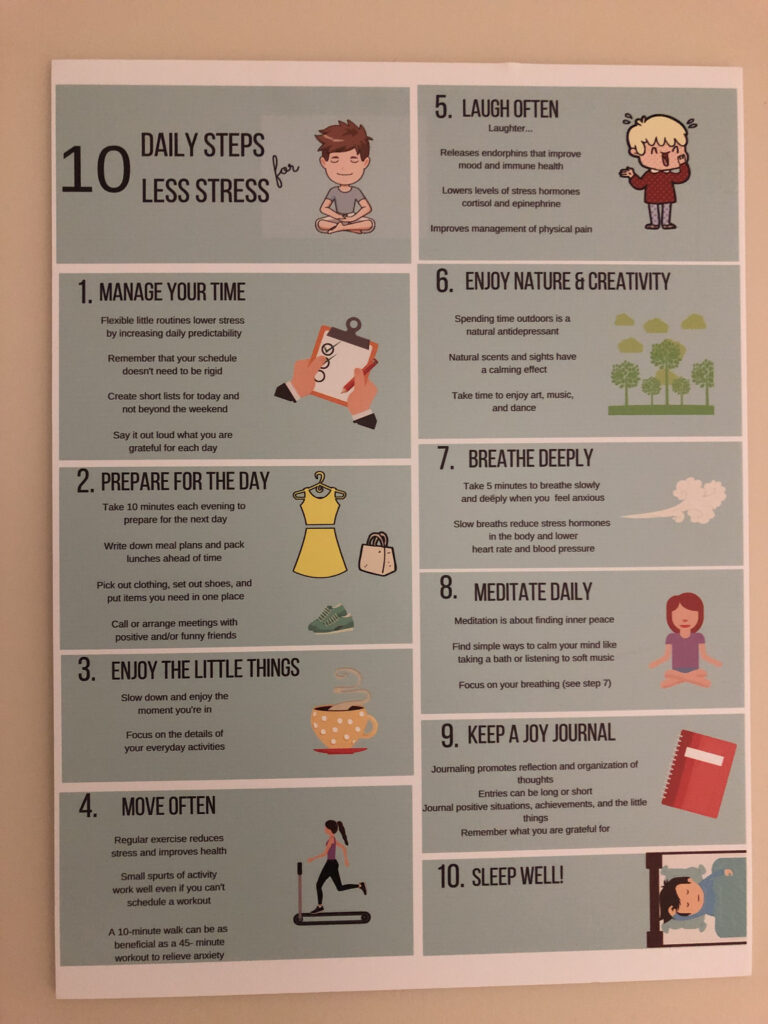

I saw this poster (above) in the psychiatric ward of a hospital. It was for the benefit of patients who are suffering from depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other psychological disorders. My heart goes out to those who suffer from these debilitating ailments. I have struggled with depression so I emphasize with these types of challenges.

I like this poster because it implies an encouraging message: “You may feel trapped in a mire of mental dissonance. Our physicians will do all they can do to help you. But here are 10 things you can start doing immediately that will help. You can do these, so do them.”

My main point is: Don’t use circumstances that are ostensibly out of your control as an excuse for inactivity. Take responsibility for discovering and doing things you can do—regardless of how small or insignificant they may seem—that will contribute to a desired outcome. I’m advocating initiative, engagement, and action; not acquiescence, passivity, or capitulation.

In life, don’t focus on things you cannot control; concentrate on things you can do and do them.

The image of the poster is small so the words may be hard to read. Here’s what it says.

Manage your time — Flexible little routines lower stress by increasing daily predictability. Remember that your schedule doesn’t need to be rigid. Create short lists for today and not beyond the weekend. Say out loud what you are grateful for each day.

Prepare for the day — Take 10 minutes each evening to prepare for the next day. Write down meal plans and pack lunches ahead of time. Pick out clothing, set out shoes and put items you need in one place. Call or arrange meetings of your everyday activities.

Enjoy little things — Slow down and enjoy the moment you’re in. Focus on the details of your everyday activities.

Move often — Regular exercise reduces stress and improves health. Small spurts of activity work well even if you can’t schedule a workout. A 10-minute walk can be just as effective as a 45-minute workout to relieve anxiety.

Laugh often — Laughter releases endorphins that improve mood and immune health; lowers levels of stress hormones, cortisol, and epinephrin; and improves management of physical pain.

Enjoy nature and creativity — Spending time outdoors is a natural antidepressant. Natural scents and sights have a calming effect. Take time to enjoy art, music, and dance.

Breathe deeply — Take 5 minutes to breathe slowly and deeply when you feel anxious. Slow breaths reduce stress hormones in the body and lower heart rate and blood pressure.

Meditate daily — Meditation is about finding inner peace. Find simple ways to calm your mind, like taking a bath or listening to soft music.

Keep a joy journal — Journaling promotes reflection and organization of thoughts. Entries can be long or short. Journal positive situations, achievements, and the little things of life. Record what you are grateful for.

Sleep well.