“You must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool.” Physicist Richard Feynman

In Leo Tolstoy’s novel The Death of Ivan Ilych, the protagonist, Ivan Ilych, is a smart, competent attorney dying from an unknown cause. Tolstoy describes a scene in which Ivan has a sobering realization while gazing at his sleeping daughter, Gerasim.

“Ivan Ilych’s physical sufferings were terrible, but worse than the physical sufferings were his mental sufferings which were his chief torture.

“His mental sufferings were due to the fact that at night, as he looked at Gerasim’s sleepy, good-natured face with its prominent cheek-bones, the question suddenly occurred to him: ‘What if my whole life has been wrong?’

“It occurred to him that what had appeared perfectly impossible before, namely that he had not spent his life as he should have done, might after all be true.”

What a probing and hopefully troubling question.

We are all wrong. Both as individuals and collectively, we are wrong about many things.

As a species (homo sapiens), we are undoubtedly and currently doing things that are terribly wrong. Just look at some of the failings of the recent past.

Slavery in the United States was the legal institution of human chattel, primarily of Africans and African-Americans, that existed from our country’s founding in 1776 until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 (only 250 years ago).

After 3,000 years of being considered a wise medical procedure, bloodletting has only recently—in the late 19th century—been discredited as a treatment for most ailments. America’s first president, George Washington, allegedly had 80 ounces of blood drained from his body in a last-ditch effort to save his life.

In the near and distant future, and for the rest of human history, humans will look with aghast at things we now consider normal and acceptable. What we accept as best-practices in the 21st century will be considered uninformed, unnecessary, even harmful, and wrong. (I’ll make a prediction: in the near future we will wonder why, in this modern era, health care was not readily available to every person on the planet.)

On a personal level, you and I are wrong about many things. There are specific areas of our lives that are wrong and need to change.

- What if you have lived a self-centered life?

- What if you have neglected your family?

- What if you have not lived authentically?

- What if you have pursued the wrong career?

- What if you are racist?

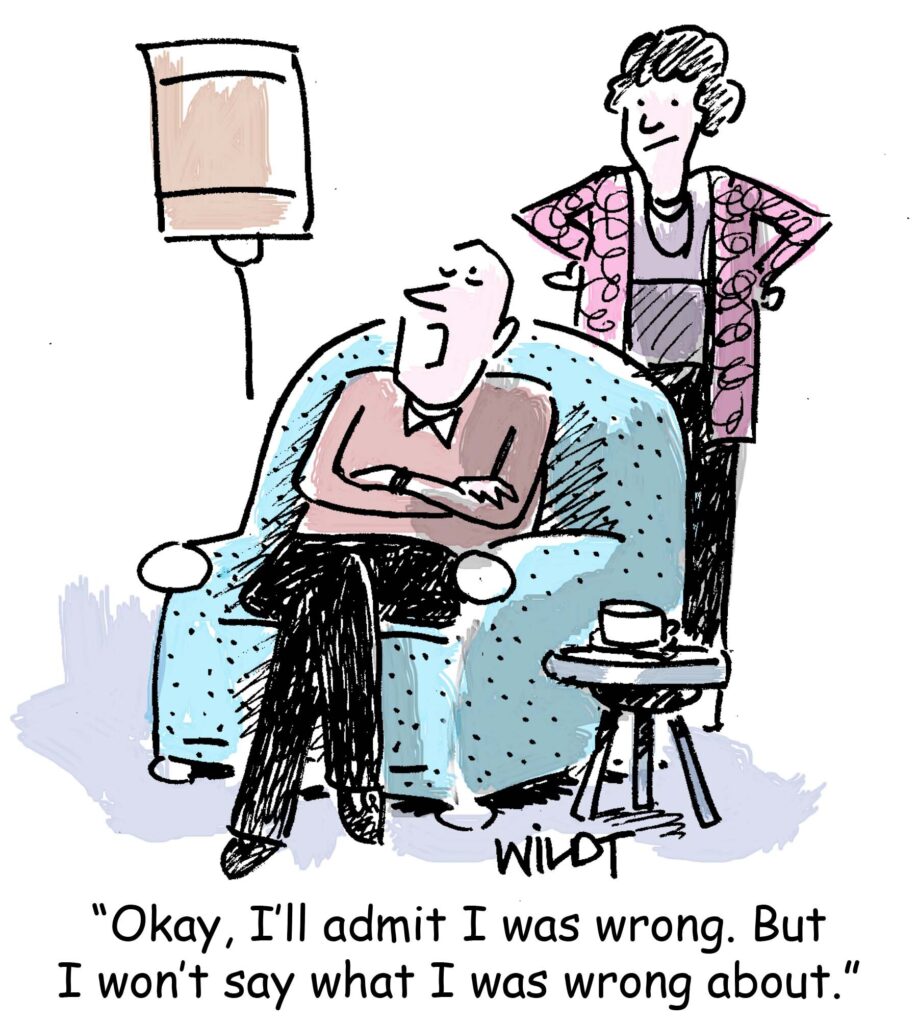

When was the last time you admitted being wrong and revised your opinion accordingly? Know this: there are areas of your life in which you are wrong. If you think you’re an exception to this statement, your pushback betrays your naiveté, lack of self-awareness, and error.

The good news is, we can change. Thoreau said, “I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life through conscious endeavor.”

Take an audit of your life; particularly consider areas in which you have a fixed mindset – areas that have been unassailable, uneditable, and beyond reproach. Also investigate areas that are part of your cultural heritage – ideologies that you inherited from your family and society. (Remember, you were not born with any opinions or beliefs; they’re not part of your DNA, you choose to endorse them.) Consider your blind spots; everyone has at least one. (You’ll need help you on this issue because you are…blinded…to your your blind spot.)

If taken seriously, this exploration could be one of the most significant and revealing events of your life.

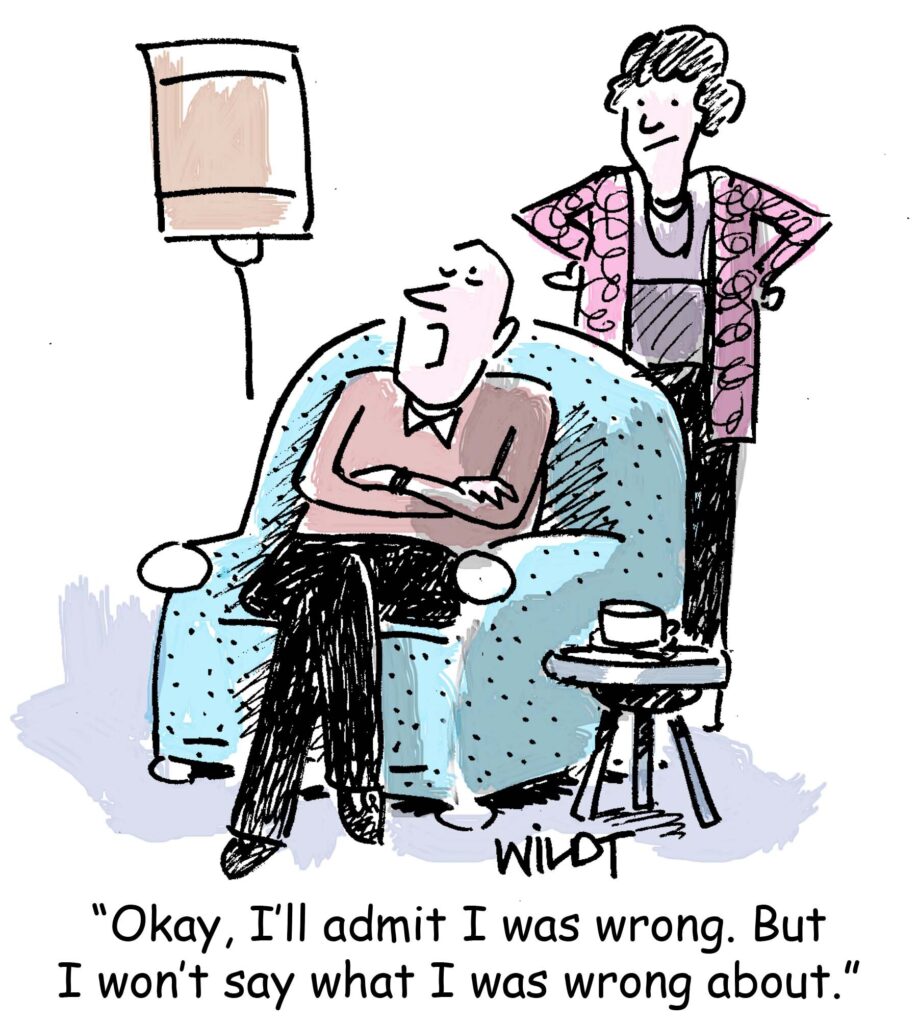

We often think that if we admit we are wrong, people will think less of us. I think just the opposite; people will admire us. I’ll close with this story from Adam Grant’s book, Think Again (page 73).

“In the early 1990s, the British physicist Andrew Lyne published a major discovery in the world’s most prestigious science journal. He presented the first evidence that a planet could orbit a neutron star – a star that had exploded into a supernova. Several months later, while preparing to give a presentation at an astronomy conference, he noticed that he hadn’t adjusted for the fact that the Earth moves in an elliptical orbit, not a circular one. He was embarrassingly, horribly wrong. The planet he had discovered didn’t exist.

“In front of hundreds of colleagues, Andrew walked onto the ballroom stage and admitted his mistake. When he finished his confession, the room exploded in a standing ovation. One astrophysicist called it “the most honorable thing I’ve ever seen.”