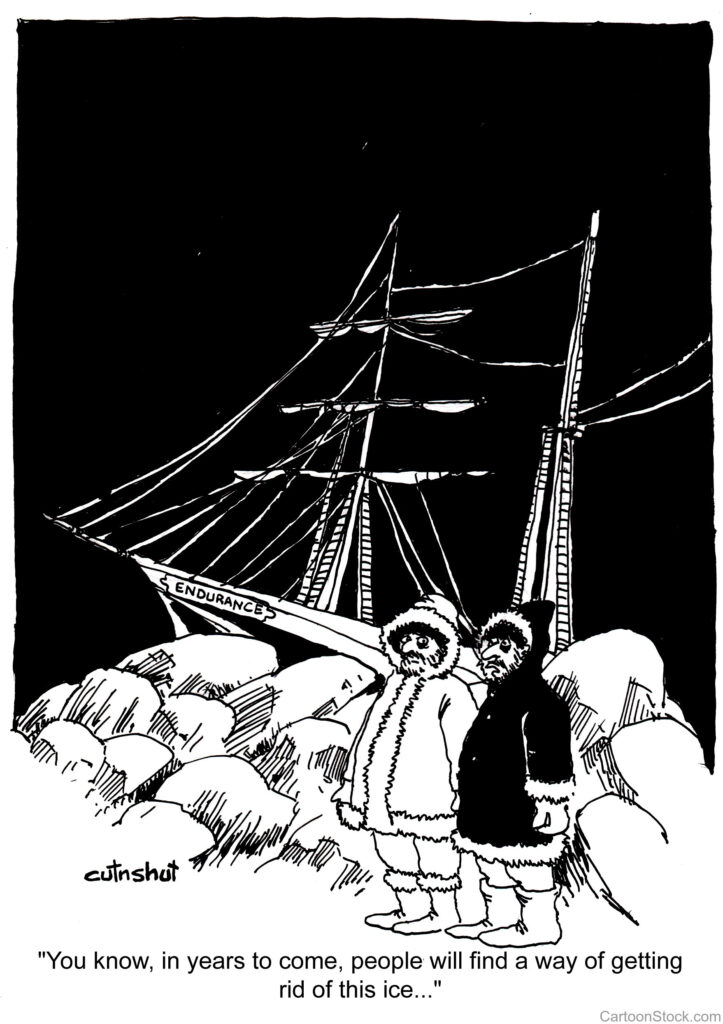

You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on. —Samuel Beckett

Psychologist Martin Seligman identifies three attitudes—all starting with the letter P—that make it difficult for us to recover from a personal setback.

- Personalization—the belief that we are at fault

- Pervasiveness—the belief that an event will affect all areas of our life

- Permanence—the belief that the aftershocks of the event will last forever

In other words, when responding to a personal problem we often think:

- It’s all my fault this happened.

- It will adversely affect my entire life.

- My life will never be the same again.

Be aware of these three tendencies and when needed, talk yourself out of them.

For instance, following a difficult divorce, healthy thinking might include:

- Acknowledge and accept responsibility for your part in the broken relationship, but only your part. Your spouse, other people, and circumstances no doubt influenced the situation, so spread out the culpability. You should bear part of the blame but not all of it.

- Don’t let the divorce permeate every area of your life. Continue to find meaning in your work. Spend time with friends. Compartmentalize the event and don’t let it soil other areas of life.

- Realize that the divorce need not permanently affect your life. Eventually, the pain and awkwardness will fade. You will survive the divorce and it need not define your life.

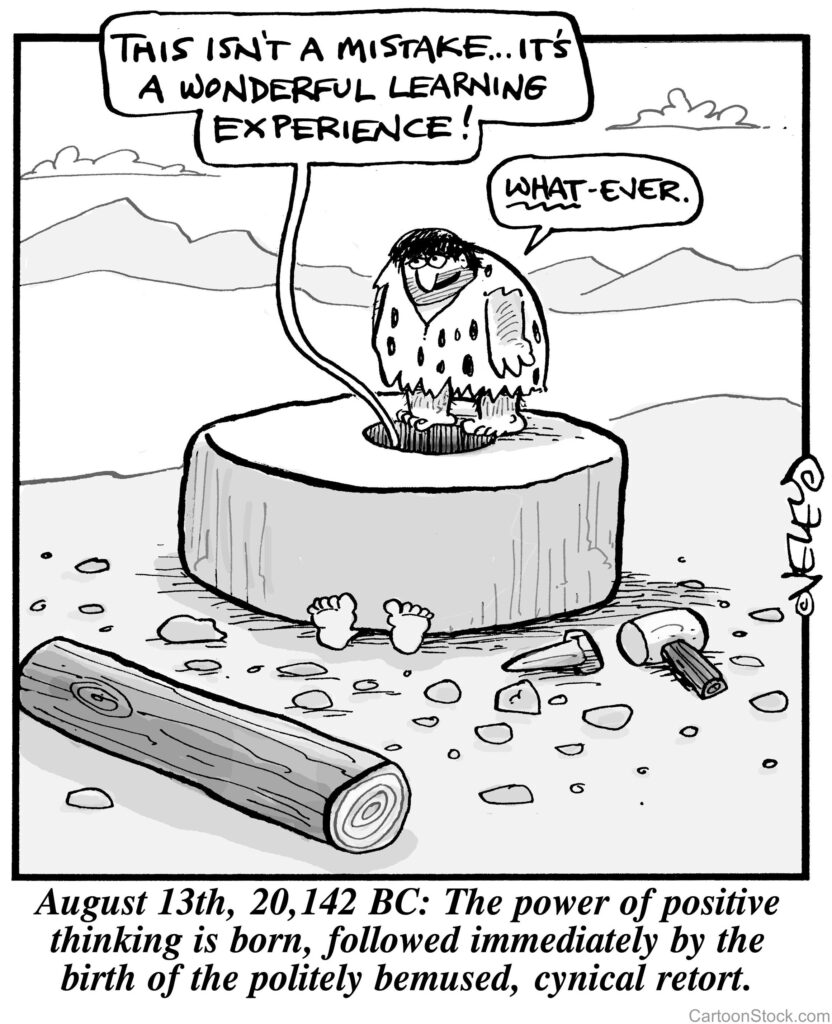

If your small business fails, healthy self-talk might sound like this:

- “If I could do it again, I would avoid the following mistakes…(name them). But, I’ve learned a lot through this setback and I’ll be a better person for it. Statistically, only 30% of new businesses make it past the first three years; if I ever try this again, because of what I’ve learned, I’ll be in that 30%.”

- “My professional life is important, but it’s not the only, or most important part of my life. I’ll continue to spend meaningful time with family and friends, enjoy my hobbies, and start looking for another job.”

- “This failure is not going to define me or determine my future. As the years go by it will become a remote memory with little or no long-term effects.”

When we mentally and emotionally dismantle these three tendencies and begin to embrace a more positive perspective, we’ll experience relief.