In the deepest poverty you should never do anything perfectly. If you do you are stealing resources from where they can be better used. Ingegerd Roth, missionary nurse in Congo

In the deepest poverty you should never do anything perfectly. If you do you are stealing resources from where they can be better used. Ingegerd Roth, missionary nurse in Congo

This principle applies anytime we are prioritizing scarce resources.

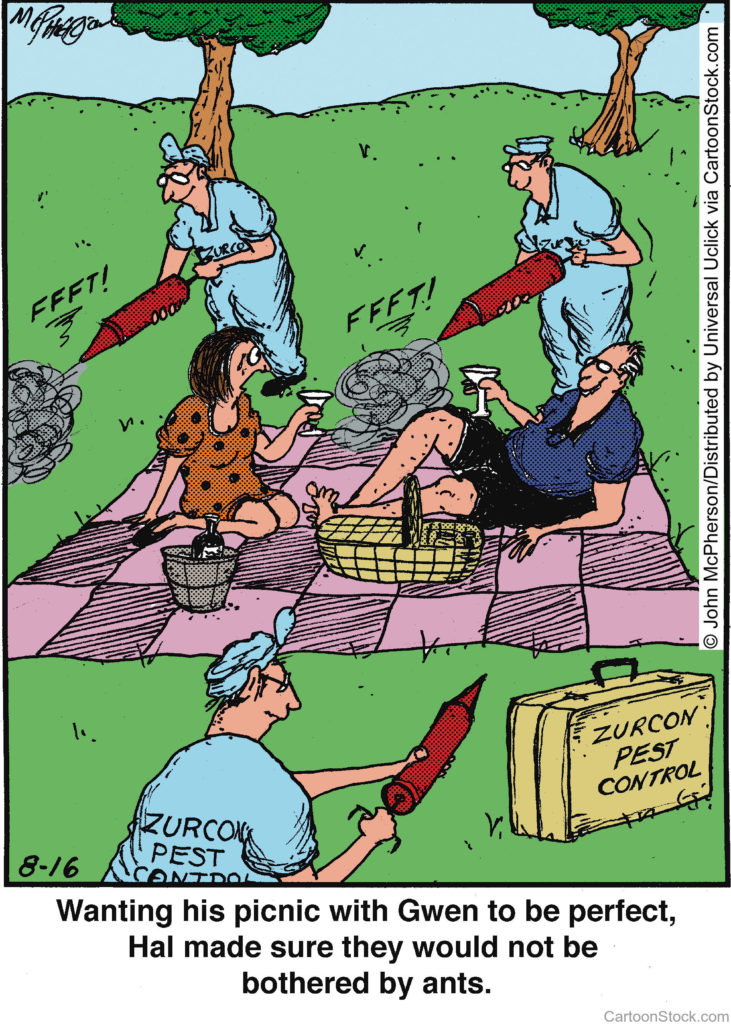

Today I spent an hour washing my car. On a scale from 1 (extremely dirty) to 10 (near perfect), it started out as a 3 and 30 minutes later it was an 8. I could have worked another hour and reached 9.5 but it would not have been worth it. To invest another 60 minutes for a 1.5 increase didn’t seem prudent. After all, it may rain tomorrow.

I had the same thought when pruning the bushes at my house. Must I pursue perfection when the bushes are still vigorously growing? Within a day or two, an energetic stem will poke through the top of the well-manicured hedge and ruin my straight line, so why bother?

Other projects require a higher standard.

- If the stakes are high, strive for perfection—we want our surgeon to be persnickety.

- If the item is a prototype to be mass-produced, be obsessive about getting the first one right. (I’m always disappointed to see typos in first-edition books published by major publishing companies.)

- If you’re a professional, people pay you to be good and fast, so be both.

But sometimes, good enough is good enough. Sometimes done is better than perfect.

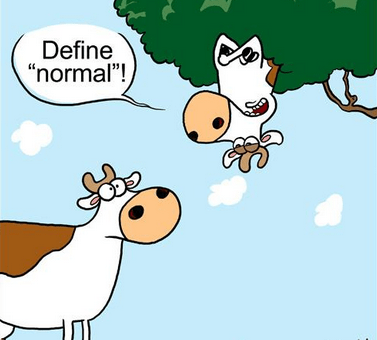

Tom Peterson adds this to the conversation: “By the way, what is perfect? Paul McCartney’s Blackbird—is it done or perfect? I lean toward perfect. But most Beatles recordings (there are around 300) are simply done. Yet their combined effect was a fantastically creative body of work.

“In the early years, the group performed relentlessly and found its sound. And when they were in song writing mode, Lennon and McCartney would set aside a series of days. Paul would drive to John’s house on the scheduled day, ‘We always wrote a song a day, whatever happened we always wrote a song a day,’ he said. ‘We never had a dry day.’

“Voltaire wrote, ‘Perfect is the enemy of the good.’ Had the Beatles performed only their perfect work perfectly, we’d have never heard of them.

“As we create projects and campaigns to improve the world, we shoot not for perfect but done. Yes, we should develop our programs as well as we can. But will any of our work be perfect? Not likely.”

Here’s a good article on the downside of perfectionism.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/better-perfect/201611/9-signs-you-might-be-perfectionist

It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society. Jiddu Krishnamurti

It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society. Jiddu Krishnamurti Last year I wrote a post titled

Last year I wrote a post titled