On June 22, 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered an attack on the French Navy after the German-French armistice was signed. Within five minutes of the initial shots being fired, nearly all of the French warships were destroyed or crippled. More than 1,000 French sailors were killed in the attack, all of whom were allies only days previously. Churchill made this decision, amidst strong cabinet opposition, to prevent a potential shift in naval superiority.

That was a gutsy call. It was also a quick decision; Churchill only had a few hours to decide.

Leaders, 90% of the decisions you make are not urgent. Simply submit them to due process: clarify the decision, seek input from your team, consider alternatives, and take time to get it right. But some decisions must be made quickly. Know and recognize the difference. Don’t be impulsive if you can submit the decision to a considered process, but don’t procrastinate when a decision must be made quickly.

Don’t be rash or impulsive, but do be decisive.

You’ll not always make the right decision. When you make a mistake, admit it, own it, and then press on.

History proved Churchill’s decision to be a good one. If he had not destroyed the French Navy, each ship would have flown a swastika and the Nazis would have ruled the seas and probably won the war.

When was the last time you had to make a major decision, quickly? What was the outcome?

In the deepest poverty you should never do anything perfectly. If you do you are stealing resources from where they can be better used. Ingegerd Roth, missionary nurse in Congo

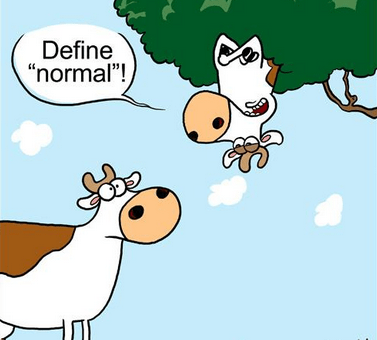

In the deepest poverty you should never do anything perfectly. If you do you are stealing resources from where they can be better used. Ingegerd Roth, missionary nurse in Congo It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society. Jiddu Krishnamurti

It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a sick society. Jiddu Krishnamurti Last year I wrote a post titled

Last year I wrote a post titled