A draft horse is a large, muscular animal that, prior to the industrial age, was used for pulling big loads. One draft horse can pull an 8,000-pound load. Two draft horses randomly linked together can pull a 24,000-pound load. If the two horses have been trained to work together they can pull 32,000 pounds

A draft horse is a large, muscular animal that, prior to the industrial age, was used for pulling big loads. One draft horse can pull an 8,000-pound load. Two draft horses randomly linked together can pull a 24,000-pound load. If the two horses have been trained to work together they can pull 32,000 pounds

This marvelous phenomenon is called synergy.

Synergy is the energy or force that is generated through the working together of various parts or processes such that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Antagonism is the extreme opposite of synergism. It is the reduction of energy due to the misalignment, friction, and opposition of individual elements that are connected. The whole becomes less than the sum of the parts. An example of antagonism is the effect between the opposing actions of insulin and glucagon to blood sugar level. While insulin lowers blood sugar, glucagon raises it.

Now, apply these thoughts to your organization.

How team members relate to one another: antagonism………………..……….synergy

The result: dysfunctional functional miraculous

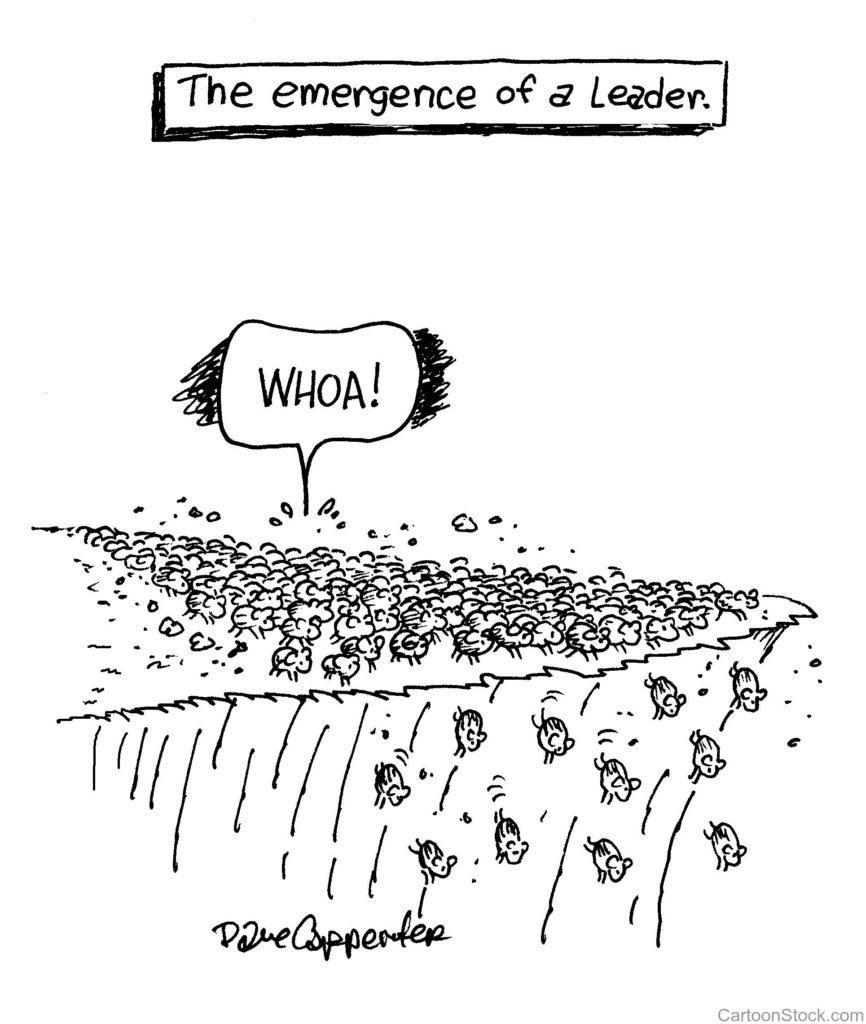

All organizational teams can be placed somewhere on the spectrum between antagonism and synergy. If your team leans far-left, you’re working against each other. If you’re in the middle, team members are probably siloed: they’re not adversely affecting each other but neither are they complementary. Teams on the far-right of the spectrum are doing amazing things together.

Use this spectrum to analyze your organization at all levels. For instance, your team may be working well together—benefiting from synergy—but your team may not be aligned with other teams in the organization.

A prerequisite for synergy (and an antidote for antagonism) is a clear vision that is shared widely and embraced deeply. A north star. A picture of the future that produces passion. A challenging but credible goal.

Wholesome communication also helps. Robust dialogue encourages transparency and respect. Lots of face-time with other team members both in meetings around the lunch table will also help.

Basic people skills are necessary. It’s hard to work with someone who is abrasive and insensitive. Team members need to “play well in the sandbox with others” for synergy to happen.

Your team’s synergy-quotient may be the most critical factor in your organization. Business writer Patrick Lencioni underscores this significance when he says, “Not finance. Not strategy. Not technology. It is teamwork that remains the ultimate competitive advantage, both because it is so powerful and so rare. If you could get all the people in an organization rowing in the same direction, you could dominate any industry, in any market, against any competition, at any time.”

Leaders, I double-dog-dare you to show this post to your team members and ask them to honestly evaluate where the team is on the scale.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

Both my daughters studied violin in high school. They excelled, taking lessons at SMU and playing in the Dallas Youth Symphony. For one concert, they played in the Meyerson Concert Hall (one of the best musical venues in the world). Mary and I were seated in the middle of the hall, our attention focused on Lauren and Sarah.

Both my daughters studied violin in high school. They excelled, taking lessons at SMU and playing in the Dallas Youth Symphony. For one concert, they played in the Meyerson Concert Hall (one of the best musical venues in the world). Mary and I were seated in the middle of the hall, our attention focused on Lauren and Sarah. Most organizations are vastly over-managed and desperately under-led. Stephen Covey

Most organizations are vastly over-managed and desperately under-led. Stephen Covey In medio stat virtus (Latin)

In medio stat virtus (Latin)