When I first started my career as a minister, a friend gave me some good advice about maintaining a healthy balance of three types of relationships: takers, balanced, and givers.

When I first started my career as a minister, a friend gave me some good advice about maintaining a healthy balance of three types of relationships: takers, balanced, and givers.

“Don, there are some relationships that will constantly drain you; you’re always giving to them but they seldom give to you. These are takers. You can’t totally avoid them (particularly in the ministry) but if they represent the majority of your relationships, you’ll burn out and lose all hope for humankind.

“In other relationships there will be a nice reciprocity; you give to them and they give to you. These associations are normal, healthy, and balanced.

“You’ll also have a few relationships in which people generously give to you with no thought of return; they will give more to you than you will give to them. Accept their magnanimity.”

In life, it’s important to have a healthy balance of these three relationship-types. If you only have “takers” they will drain you dry. Balanced relationships, in which there is a mutual giving and receiving, should be the dominate type. And be extremely grateful if you have those rare friends who delight in freely and unconditionally giving to you with no thought of return.

I think I can live a reasonably sane life if I maintain a ratio of 30/60/10 (30% of my relationships are takers, 60% are balanced, 10% are givers).

For a moment, consider what type of person you are to other people.

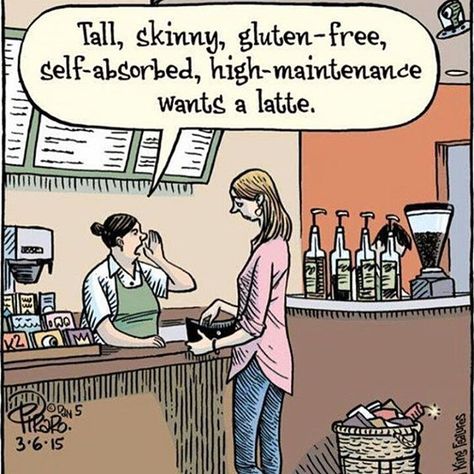

- Are you primarily a taker; high-maintenance and selfish?

- Or do you strive to maintain balance in your relationships—you’re sensitive about the give and take ratio of relationships and work toward equilibrium.

- Name several adult relationships in which you are, by choice, the primary giver.

I now express deep appreciation to these people in my life who have given more to me than I have given to them: Dean F., Mike F., David H., John M., Chuck S., Jay W., Ruth M., and others.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

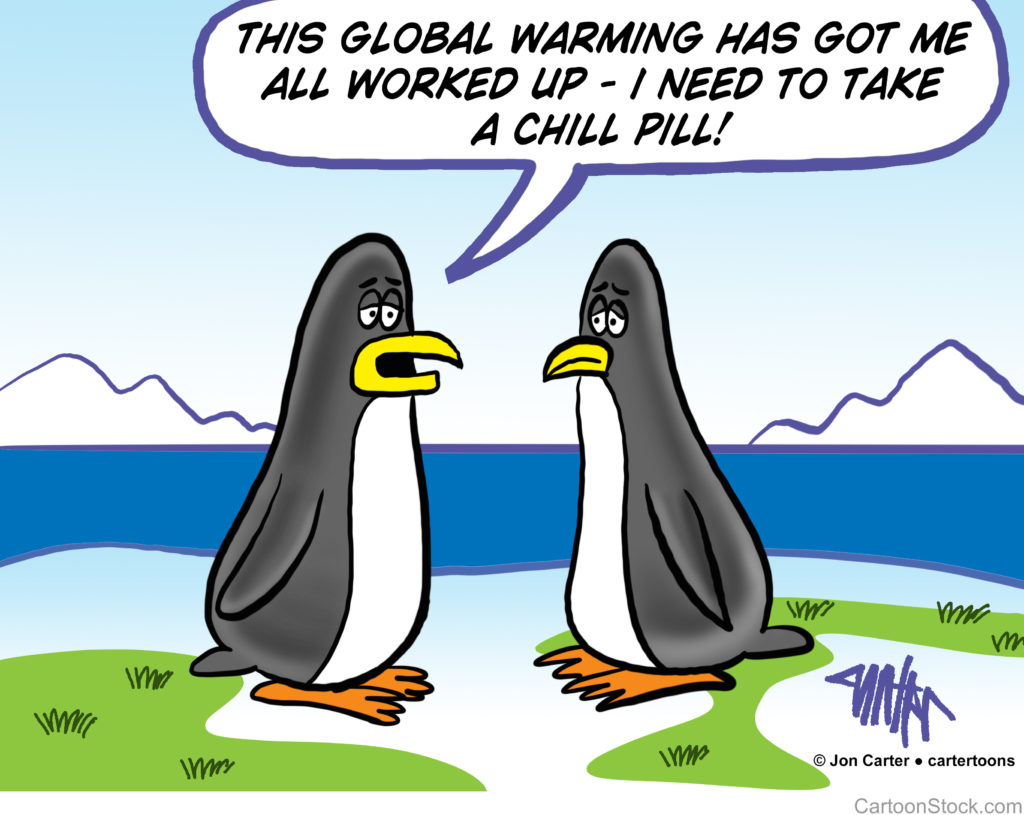

Sometimes, I trip over inconsequential issues. I obsess about issues that won’t matter six months from now, or even six hours from now. When this happens, I need to take a “chill-pill” and drop it.

Sometimes, I trip over inconsequential issues. I obsess about issues that won’t matter six months from now, or even six hours from now. When this happens, I need to take a “chill-pill” and drop it. Sometimes, when I consider what tremendous consequences come from small things, I am tempted to think…there are no small things. — Barton

Sometimes, when I consider what tremendous consequences come from small things, I am tempted to think…there are no small things. — Barton