There are many opinions on what these three terms mean and how they relate to each other. Here are my thoughts.

There are many opinions on what these three terms mean and how they relate to each other. Here are my thoughts.

All three terms describe a process whereby a person can relate to the emotional state of another person. In this order—sympathy, empathy, compassion—they describe an ever-deepening level of concern and involvement.

Sympathy

Sympathy is a mental understanding of the plight of another person. I sympathize with the plight of starving children in Africa and with the person who has a flat tire alongside the road. I understand that it is a plight. I can sympathize without getting emotionally engaged or taking any action. I’m simply embracing facts.

Empathy

Empathy takes me deeper. Not only do I understand another person’s pain, I also feel what she is feeling. My emotions are stirred, not by what is happening in my life, but by what is happening in someone else’s life. I feel what a person is feeling.

I remember the first time I deeply empathized with someone. One day, when I was a young pastor, I visited a woman who had recently attempted suicide. As she described the painful circumstances of her life and the despair she was feeling, she began to weep. Suddenly, I began to weep. I asked myself, “Why am I weeping? My life is going quite well.” I then realized that I was weeping because I was feeling someone else’s pain, not my own.

Compassion

Compassion takes me deeper still. Building on sympathy and empathy, it compels me to become physically involved in relieving another person’s pain; it calls me to action.

The story of the Good Samaritan illustrates the difference between sympathy, empathy, and compassion.

Jesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road, and when he saw him he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was, and when he saw him, he had compassion. He went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he set him on his own animal and brought him to an inn and took care of him. And the next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, ‘Take care of him, and whatever more you spend, I will repay you when I come back.’ Which of these three, do you think, proved to be a neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” He said, “The one who showed him mercy.” And Jesus said to him, “You go, and do likewise” (Luke 10:30-37, ESV).

The priest and Levite noticed the distressed man and may have even empathized with him, but they did nothing to relieve his distress. The Samaritan had compassion on the man and it moved him to act.

In reflecting on the parable of the Good Samaritan, Martin Luther King Jr. said, “I imagine that the first question the priest and Levite asked was: ‘If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?’ But by the very nature of his concern, the good Samaritan reversed the question: ‘If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?’”

I’m not suggesting that empathy and sympathy are unimportant or lacking; they are thoughtful and kind impressions. Nor am I suggesting that we must always demonstrate compassion; logistically it’s impossible to respond to every need.

The great value of these three functions is that they divert our focus from ourselves to others. Instead of being ego-centric we focus on others and become altruistic and magnanimous. And that’s a good thing.

Sympathy says “I’m sorry your hurting.” Empathy says “I hurt with you.” Compassion says “I’ll stick around until the hurt is gone.”

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

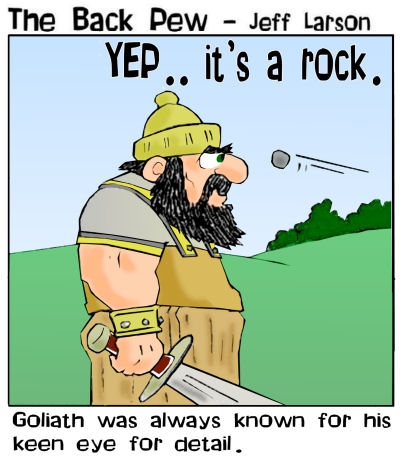

In the epic biblical story of David and Goliath, David was confident that he could kill the giant because, “Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be like one of them” (1 Samuel 17:36).

In the epic biblical story of David and Goliath, David was confident that he could kill the giant because, “Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be like one of them” (1 Samuel 17:36).

What information consumes is attention. A wealth of information means a poverty of attention. Herbert A. Simon, cognitive scientist

What information consumes is attention. A wealth of information means a poverty of attention. Herbert A. Simon, cognitive scientist Give me enough ribbons to place on the tunics of all my soldiers and I can conquer the world. Napoleon

Give me enough ribbons to place on the tunics of all my soldiers and I can conquer the world. Napoleon There are many opinions on what these three terms mean and how they relate to each other. Here are my thoughts.

There are many opinions on what these three terms mean and how they relate to each other. Here are my thoughts.