There are many things in life that we cannot control: other people, the weather, random events…but there are many things we can control and we should focus on those.

Here are six things we can easily do—every day— that require little time and effort but are beneficial.

Maintain good posture.

Whether you’re sitting or standing, have good posture. You’ll look and feel better.

Here’s a good article on good posture:

Drink a large glass of water as soon as you get up in the morning.

A survey of 3,003 Americans found that 75% had a net fluid loss, resulting in chronic dehydration. Are you among that 75%?

Dehydration has dire effects but is easily avoided.

Drink a glass of water when you first get up in the morning. It will begin the hydration process and help keep the issue on your mind throughout the day.

Here’s an article on how much water you should drink per day.

Here’s an article on dehydration.

Strengthen and favor your core muscles.

Your core muscles are so named because of their location and importance. Our center of mass is usually located just below the navel and halfway between the abdomen and lower back, which is midway between the mass of the upper and lower body. When walking, working, bending, or leaning over, I think of my center-point and keep my body balanced over it. Most evenings I do a series of exercises that stretch and strengthen my core muscles.

Here’s an article and video on good exercises to strengthen your core muscles.

Develop a pleasant “resting face.”

Your “resting face” is the way your face looks when you are at ease, with facial muscles relaxed.

Your “engaged face” is the way your face looks when you are consciously manipulating your face to appear more engaged, approachable, and friendly. I’ve also heard this called a “yes face.”

Most people have an unfriendly looking resting face. At best it’s hard to read, at worst we look sad, unapproachable, unengaged, and even upset.

To display an engaged face, simply raise the eyebrows and forehead, open up the eyes, and smile.

Here’s a post I wrote on this subject.

Memorize one significant thought a week and meditate on it.

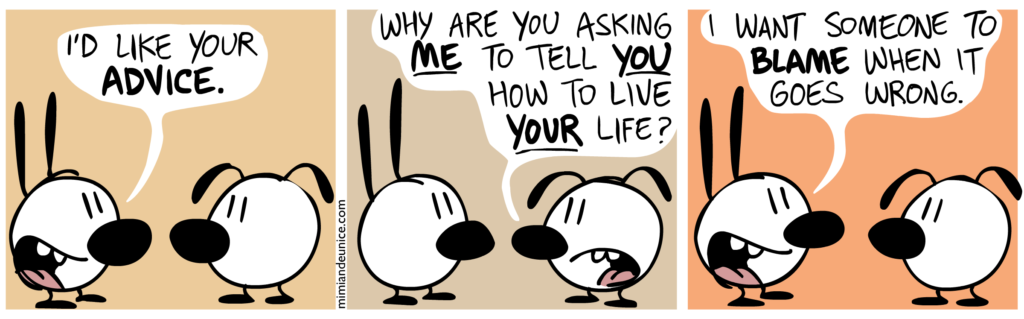

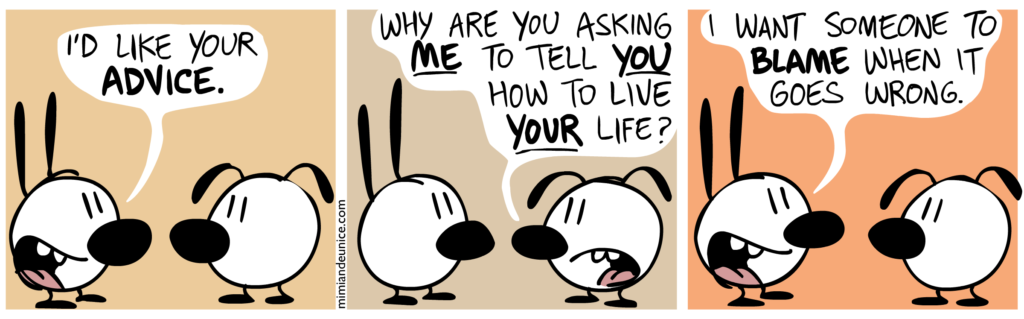

Here’s a mental discipline I enjoy, benefit from, and constantly do: I identify a significant thought, memorize it, meditate on it, apply it to my life, and when possible, discuss it with other people.

This process is a key to personal growth and change.

Here are some thoughts I’ve recently meditated on:

-

- “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” —Einstein

- It’s amazing how much an organization can accomplish if no one cares who gets the credit for progress.

- “Envy is the most stupid of vices, for there is no single advantage to be gained from it.” Balzac

Here’s a post I wrote on this subject.

Express gratitude daily.

There are many advantages to expressing gratitude, not just thinking thoughts of gratitude or feeling grateful, but actually expressing it.

-

-

- It helps develop a positive attitude.

- It’s an antidote for being negative and pessimistic.

- It reinforces our remembrance of positive experiences.

- When we express gratitude to people for specific things they have done, they are encouraged and their behavior is affirmed.

Here’s a post I wrote on this subject.

In the past few years, I’ve developed a new catchphrase: “There are some things you cannot do; but what you can do, do.”

These are six things everyone can do.