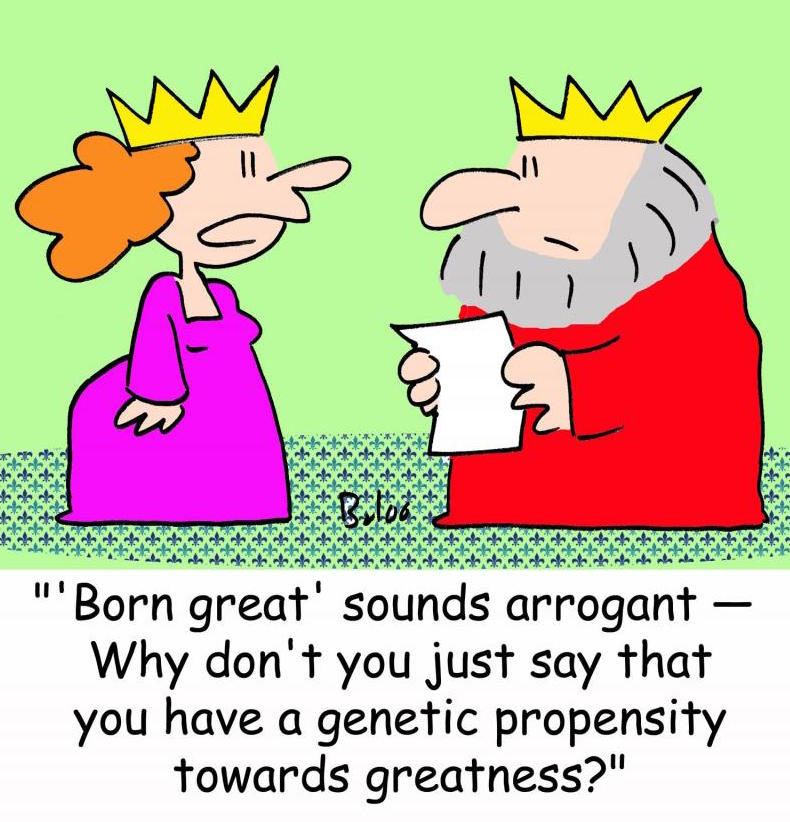

Expressions of arrogance and pride are distasteful, almost comical.

Expressions of arrogance and pride are distasteful, almost comical.

Expressions of humility and modesty are attractive and honorable.

I am deeply moved by expressions of humility.

- I have a friend who is President of a private bank. When he introduces himself in public he says, “My name is _______ and I work at _____ bank.”

- I have a friend who was President of a major university. When he speaks of that time in his life he says, “For several years I served on the leadership team at ___________.”

- I have a friend that I knew for four years before I discovered he has a Ph.D. in geology from a major research university.

These men and women are exceptional in their character, credentials, and experiences. They have accomplished a lot in life. But it takes a long time to discover their depth, because they are so humble. They have a lot more behind the counter than they put out on the shelf.

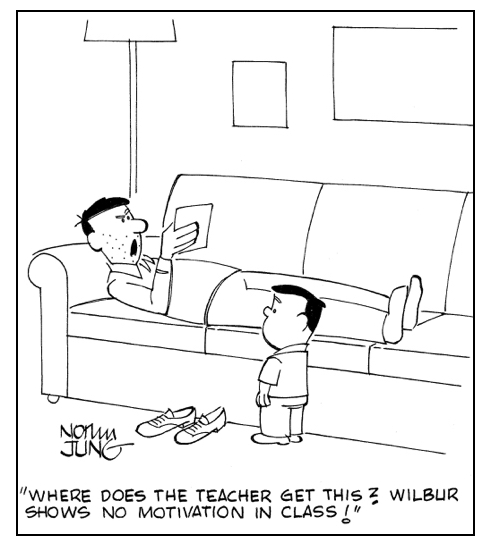

How about you? Are you eager to tell people what and who you know? When meeting people for the first time, do you quickly try to impress them with your credentials and experiences, or is your discloser slower and more subtle? Do you overstate or understate your strengths and assets? Do you hide your weaknesses and failures, or do you acknowledge them as a natural part of your life’s narrative?

I love the following story because it is utterly fascinating and, the protagonist exemplifies what I’m advocating in this essay.

The 17th century French mathematician Pierre de Fermat proffered a theorem that became the Holy Grail of math problems for 350 years: prove there are no whole-number solutions for this equation: xn + yn = zn for n greater than 2. Some mathematicians spent their entire lives trying to solve the problem; many thought it was impossible.

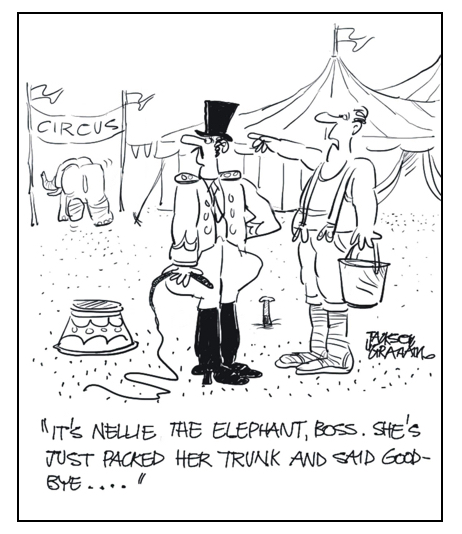

On June 23, 1993, Andrew Wiles—a quiet, unassuming professor of mathematics at Princeton University—stood before his peers at a conference in Cambridge and for several hours scribbled math equations on the chalkboard. Finally, he said, “I think I’ll stop here,” and put down the chalk. He had solved Fermat’s Enigma. With little fanfare, he had deciphered one of the most complicated problems in mathematics and then simply said, “I think I’ll stop here.”

Understated. Humble. Let’s follow suit.

[The book, Fermat’s Enigma by Singh, tells the whole story; it is a must-read. There are many videos on YouTube about Fermat’s Theorem. For a four-minutes summary click here.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

Summary

What? — Humility is a noble virtue; bragging is not. We should be slow to reveal the depths of our personal assets and strengths.

So what? — Always have more behind the counter than you put on the shelf.

Now what? — If necessary, adjust your thinking about this issue.

[callout]Occasionally, I’ll include in a post, the link to an interesting article which addresses a different topic than the post.

Here’s a great article – The Benefits of Despair – written by Lisa Feldman (June 5, 2016; New York Times) She shares some good thoughts about why “emotional granularity” is beneficial. Sam Harris says, “We read for the pleasure and benefit of knowing another person’s thoughts.” Read and benefit from Feldman’s insights. Click here for the article. [/callout]

Role models provide an effective shortcut to learning. Find someone who is succeeding at what you want to do or who you want to be, study her, and copy her actions.

Role models provide an effective shortcut to learning. Find someone who is succeeding at what you want to do or who you want to be, study her, and copy her actions. Beginnings are important. First impressions, initial greetings, the commencement of a trip—how something starts is important. The “front door” is critical.

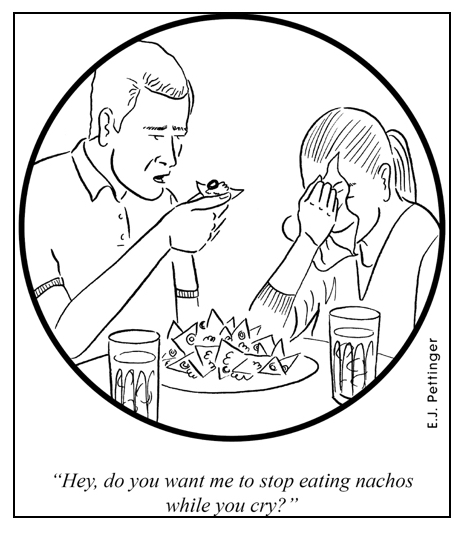

Beginnings are important. First impressions, initial greetings, the commencement of a trip—how something starts is important. The “front door” is critical. Where have you been? the mother demanded. The little girl replied, “On my way home, I met a friend who was crying because she had broken her doll.” “Oh,” said her mother, “then you stopped to help her fix the doll?” “Oh, no,” replied the little girl, “I stopped to help her cry.”

Where have you been? the mother demanded. The little girl replied, “On my way home, I met a friend who was crying because she had broken her doll.” “Oh,” said her mother, “then you stopped to help her fix the doll?” “Oh, no,” replied the little girl, “I stopped to help her cry.”