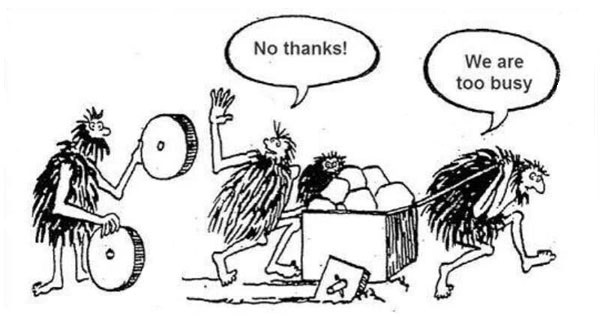

Fifty years ago, when I first started traveling internationally, all luggage was heavy and carried by hand. Thirty years ago, a Delta pilot had the good idea of putting two wheels on luggage so it could we pulled. Travel Pro was the first company to produce the wheeled luggage. Twenty years ago, manufacturer’s started putting four wheels on luggage, making it easier to manipulate. Ten years ago manufacturer’s started using light weight materials. When empty, I can pick up my large suitcase with one finger.

What will be the next improvement in luggage? We don’t know, but it will happen because the luggage industry will continue to improve its prosaic, simple product. This continuous improvement is a good example of the Kaizen strategy.

Here’s the backstory.

In 1950, 21 of Japan’s most important business leaders attended a dinner party in Tokyo. American statistician W. Edwards Deming was the keynote speaker. Deming said that the key to restoring Japan’s post-war economy was to pursue a simple strategy of continuous improvement of all products and services. Collectively, and without regulatory or legislative involvement, these leaders adopted Deming’s recommendations, which eventually led to a manufacturing and economic renaissance.

In two decades, Japanese products, which had been referred to as “Jap scrap,” became synonymous with “quality” and “super-engineering.” These quality improvement methods took Japan, within one generation, from a country that had been completely destroyed in 1945 to the number two economic power in the world. The Japanese called the process “kaizen,” which means “continuous betterment” or “continuous improvement.”

How can we benefit from this simple concept?

Never be content with the way things are; continually strive to make things better. Adopt the mindset that everything is a work in progress and that incremental improvements can always be made. Continually ask, “How can this be improved?”

Apply the Kaizen strategy to your personal life. Make it part of your modus operandi.

-

-

- Embrace the thought that everything – all products and systems – can be improved. How you make your coffee in the morning, your vacations, your library – everything can be improved. Even things that are mundane and simple – brushing your teeth – can be improved.

- Look for small, incremental changes, not just large major changes.

- Kaizen is continuous; don’t ever stop searching for ways to make something better.

- Leaders, this is an important part of your job. Apply the Kaizen method to all processes, systems, services, events, and products. If your organization is large enough, create a position dedicated to Kaizen, someone who will constantly consider ways for every part of the organization to improve.

-