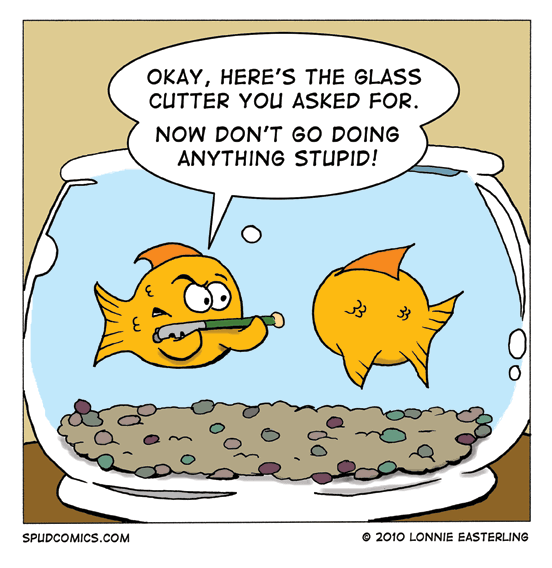

There is a species of fish – the Japanese carp, known as the Koi – that will grow in size only in proportion to the size of the body of water it is in. When placed in a small aquarium the fish will only grow to be two or three inches long. If placed in a larger body of water, it will grow to six to ten inches. When placed in a large lake, it can reach its full size of two or three feet in length.

There is a species of fish – the Japanese carp, known as the Koi – that will grow in size only in proportion to the size of the body of water it is in. When placed in a small aquarium the fish will only grow to be two or three inches long. If placed in a larger body of water, it will grow to six to ten inches. When placed in a large lake, it can reach its full size of two or three feet in length.

In like manner, your environment can inhibit and limit your personal growth and development. It may be the job you’re in—although you feel secure and the work is tolerable, you’re stuck in a mind-numbing environment and your head is hitting the proverbial glass ceiling. It may be the town you live in—the provincial mentality is stifling. The friends you associate with may be stymying—you may need a more intellectually invigorating group.

But the right environment can stimulate your growth and help you reach your potential. Fortunately, you do have control over this dimension of life; you can choose where you work, you can move to a city that inspires you, and you can choose friends that will stretch you.

To illustrate this idea, I’ll use two of my family members.

After graduating from college, my daughter, Lauren, made some bold moves that placed her in a “large pond.” First, she moved from a small college town in Texas to New York City. She got a nice and adequate job, but after working there for a few years she realized she needed a greater challenge so she went to work at American Express. Soon, AMEX moved her to Singapore for a year, then back to NYC. In the meantime, she completed a master’s degree from Columbia. Can you sense the mix of challenges, thrills, fear, insecurities and joys involved in making these moves?

My son-in-law, Jonathan, is a board certified emergency room physician. He has served two tours-of-duty in the Navy. For one of his assignments he was stationed at Camp Bastion in Afghanistan. It was one of the busiest trauma centers in the world. He saw more and learned more in nine months than some physicians would see and learn in a lifetime here in the states. It was a large pond.

Don’t underestimate the courage it takes to change environments and the effort it takes to adjust to and flourish in a new one. It can be intimidating and challenging. You may even fail. But it’s worth the risk and effort. Life is too short to waste; it’s not a dress rehearsal, and it’s the only one you get.

You don’t want this written on your tombstone: Died, 55 years old; buried, 70 years old.

[reminder]Share your thoughts about this essay. [/reminder]

Summary

What? – Our personal growth and development can be enhanced or stymied by our environment.

So what? – Beware of the times in life when you are too comfortable and unchallenged. You may need to “get into a larger tank.”

Now what? – Analyze where you are in life. Does your environment provide the room and stimulus for personal growth? If not, what will you do?

Leaders – Do you create environments and opportunities in your organization in which people can grow and develop? Consider each member of your team and customize a plan that will optimize their personal development.

Several years ago Mary and I toured Morocco. We started in Marrakesh, then went to Fez and ended up in Casablanca, which is a really rough, dirty city. (The movie Casablanca was filmed in Hollywood, so it’s not an accurate depiction of what the city really looks and feels like).

Several years ago Mary and I toured Morocco. We started in Marrakesh, then went to Fez and ended up in Casablanca, which is a really rough, dirty city. (The movie Casablanca was filmed in Hollywood, so it’s not an accurate depiction of what the city really looks and feels like). Join me in testing the view that most individuals and companies are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity, and that the much higher levels of performance reached in emergencies are actually more closer to true, sustainable potentials than are the “normal” levels of performance. Robert Schaffer

Join me in testing the view that most individuals and companies are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity, and that the much higher levels of performance reached in emergencies are actually more closer to true, sustainable potentials than are the “normal” levels of performance. Robert Schaffer Peter Drucker coined the phrase “organized abandonment” to describe the process whereby we can free up resources that are committed to maintaining things that no longer contribute to performance and no longer produce results.

Peter Drucker coined the phrase “organized abandonment” to describe the process whereby we can free up resources that are committed to maintaining things that no longer contribute to performance and no longer produce results.