Have you ever wondered why negative events seem to impact us more than positive events?

Have you ever wondered why negative events seem to impact us more than positive events?

- The comment “You’ve gained a lot of weight” will hurt us more than the comment “You look nice” will encourage us.

- We remember the course we failed in college more than we do the ones we excelled at.

- The feelings of anger we have toward a driver that cuts in front of us will stick with us longer than the joy we have when viewing beautiful wildflowers on the side of the road.

In their must-read book, The Net and the Butterfly, authors Cabane and Pollack explain why negative things “stick” quicker and last longer than positive events, and what we can do about it.

“Negative things produce more neural activity than equally intense positive things. We are quicker to recognize the negative in our world. The amygdala, the fire alarm of your brain, uses two-thirds of its neurons to look for the negative. These negative things get stored into memory almost immediately. Positive things need to be held in awareness for twelve seconds to transfer to longer-term memory. This is why gratitude, meditation, and loving-kindness are necessary: we need to focus on the good for our brain to be able to truly remember it. As Rick Hanson puts it, your ‘brain is like Velcro for negative experiences but Teflon for positive ones.’”

One good remedy for this biological predisposition toward the negative is to systematically and regularly meditate on positive thoughts (and, according to the authors, do so for at least 12 seconds). I’m going to do that right now by meditating on the following thoughts:

- Several months ago, I visited my favorite edifice in the world—St. Peter’s Basilica.

- Last week I spent an entire morning with my favorite little person—my grandson, Benjamin.

- I have so many good and faithful friends. I’ll think of a few right now: Dean, Chuck, Mike, Wayne, Jonathan.

- My fig tree is blossoming in the backyard.

The apostle Paul said it this way: “Fix your thoughts on what is true, and honorable, and right, and pure, and lovely, and admirable. Think about things that are excellent and worthy of praise.” A simple but highly effective exercise. It was good advice when it was written two thousand years ago, and it will benefit us today.

Meditation on positive thoughts.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

I enjoy cruising because it’s a win-win situation; it works for me and it works for the cruise line. I recently paid only $1,350 for a luxurious, 16-day transatlantic/European cruise (Miami to Rome) which included all meals, lodging, transportation, and entertainment. One evening, as I was munching on a filet mignon, I wondered, “How do they make this work, financially?” I don’t know, but obviously they do, or they wouldn’t be in business.

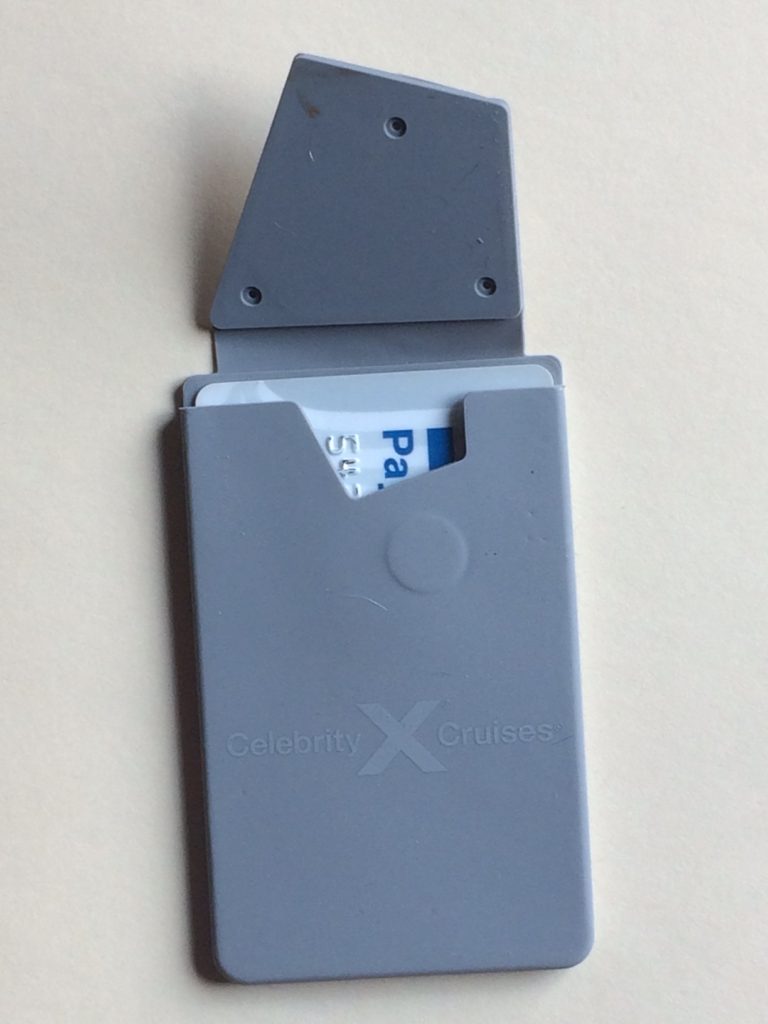

I enjoy cruising because it’s a win-win situation; it works for me and it works for the cruise line. I recently paid only $1,350 for a luxurious, 16-day transatlantic/European cruise (Miami to Rome) which included all meals, lodging, transportation, and entertainment. One evening, as I was munching on a filet mignon, I wondered, “How do they make this work, financially?” I don’t know, but obviously they do, or they wouldn’t be in business. Recently, I was on a European cruise on which every passenger was given a nice faux-leather case in which to keep your stateroom keycard. (See picture above.) Though a nice, generous gesture, it quickly became a fiasco.

Recently, I was on a European cruise on which every passenger was given a nice faux-leather case in which to keep your stateroom keycard. (See picture above.) Though a nice, generous gesture, it quickly became a fiasco. Time is a precious commodity. If traded on the commodities market, its value would be incalculable. But alas, time cannot be bought or sold. And while the length of our lives varies and is unpredictable, the number of hours we have in each day is fixed.

Time is a precious commodity. If traded on the commodities market, its value would be incalculable. But alas, time cannot be bought or sold. And while the length of our lives varies and is unpredictable, the number of hours we have in each day is fixed.