The mother asked, “Where have you been?” Her little girl replied, “On my way home I met a friend who was crying because she had broken her doll.”

“Oh,” said her mother, “then you stopped to help her fix the doll?”

“No,” replied the little girl, “I stopped to help her cry.”

This story illumines the best way to respond to someone who is hurting: offer comfort.

Hurt and pain are inevitable. It’s not a matter of if we’re going to be hurt, but rather when and how we will deal with the pain.

Pain takes many forms. It can be physical (a sprained ankle), social (exclusion from a group), or emotional (embarrassment, disappointment). Some hurts may be perceived as relatively minor—“I was embarrassed at lunch today when I spilled ketchup on my shirt.” Others are major—“My father abandoned me.”

There’s only one antidote for hurt—comfort.

Here are some practical suggestions on how to comfort other people.

Learn to sense when someone is hurting and be willing and available to help her.

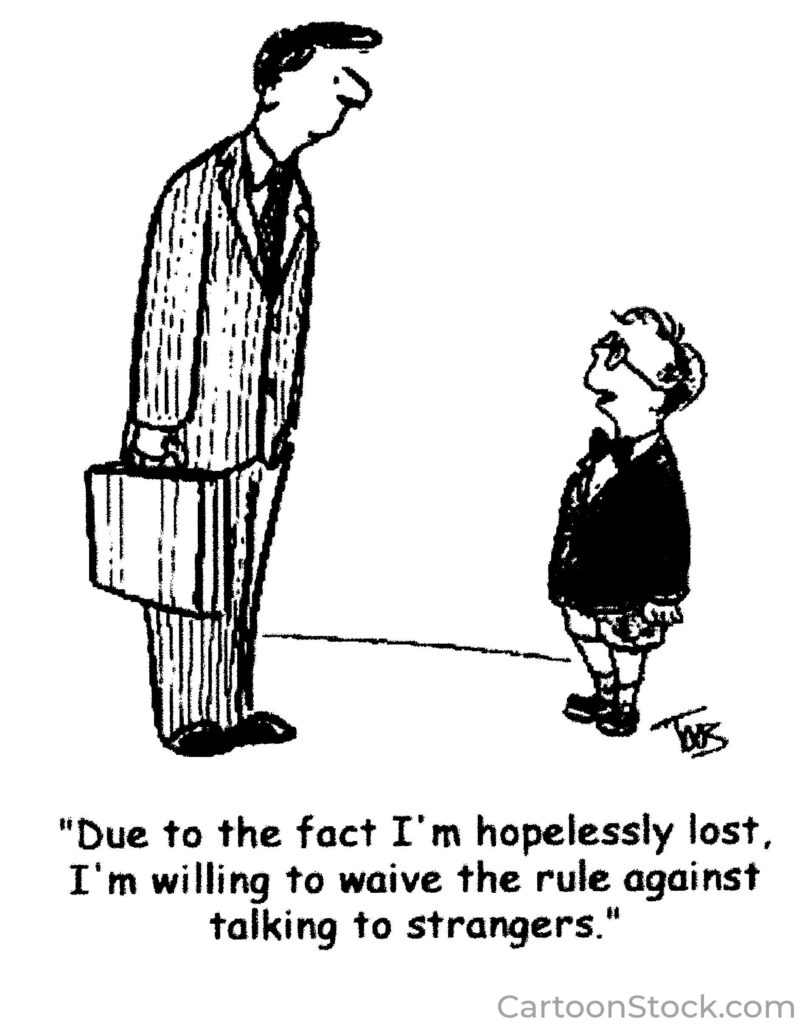

We’re often unaware when people are hurting. Sometimes circumstances will give us a clue (physical illness, death of a loved one, divorce or separation, loss of a job), but often it’s not so apparent. So be discerning and learn to recognize when people need comforting

When you do sense that someone is hurting, are you willing to slow down and take the time to minister comfort or do you choose not to “go there”? You must be discerning, willing, and available.

When someone is hurting, if possible, enter her physical world.

While it is possible to comfort someone over the phone or in an email, it’s best done in person and preferably in the hurting person’s space. If your friend is hurting, instead of suggesting, “Susan, it sounds like we need to talk. Can you drop by my office this afternoon?” it’s better to offer, “Susan, it sounds like we need to talk. Can I come by your office this afternoon?”

Enter her mental and emotional world.

Humans live in at least three “worlds” simultaneously: physical, mental, and emotional. While it’s easy to determine where someone is physically, it’s more difficult to determine where she is mentally and emotionally. But to comfort effectively it helps to understand what a person is thinking and feeling. Often, just asking directly – “How are you feeling? What are you thinking?” – is sufficient. At other times it takes more effort, particularly if the person is guarded and reluctant to share.

Listen.

A good comforter must be a good listener. Let the one who is hurting do most of the talking; if you talk too much you’ll inevitably engage in unproductive responses.

When someone needs comfort, avoid these unproductive responses.

-

-

- Advice/instruction – “Let me give you some steps of action to solve the problem.” Or, “Maybe next time that happens you should…”

- Logic/reasoning – “Let me analyze the situation and tell you why it happened.” Or, “I think the reason this happened was because…”

- Pep talk – “You’re a winner! You’ll make it through these tough times!” Or, “I’m sure tomorrow will be a better day.”

- Minimize – “Sure it hurts, but get it in perspective, there’s a lot going on that’s good.” Or, “Aren’t you being overly sensitive?”

- Anger – “That makes me so mad! They shouldn’t get away with that!” Or, “I’m so upset that you keep getting yourself hurt.”

- Martyr’s complex – “I had something similar happen to me.” Or, “After the kind of day I had, let me tell you what hurt really feels like.”

- Personal fear/anxiety – “I’m afraid that what has happened to you is going to affect my life too.”

- Silence/neglect – Not saying anything.

- Fix it – “I can’t believe that salesman talked to you like that. I’m calling the store right now and talking to his boss.” Or, “Sorry you had a flat tire on that lonely road. Tomorrow I’ll get a set of new tires.”

- Spiritualize – “Well, you know that God will work all of this out for your good.”

While some of these responses may be appropriate to share after the hurting person has been comforted, they don’t work as the initial response.

Learn the “vocabulary of comfort.”

Often, we don’t know what to say to someone who is hurting because we’ve never developed an appropriate vocabulary. We don’t need to say a lot, a few choice sentences are sufficient. Here are some suggestions.

-

-

- I’m so sorry that you are hurting.

- It saddens me that you’re hurting. I love you and care for you.

- I’m committed to help you through this difficult time.

- It saddens me that you felt _________ (embarrassed, rejected, belittled). I know that must have hurt.

- I know that you’re hurting. I just wanted to come be with you.

When speaking words of comfort, it’s also important that our tone of voice complement what is being said. Our speech should be warm, sincere and gentle.

Use appropriate non-verbal gestures.

A warm embrace or gentle touch can express comfort. Tears shed for someone else can convey love beyond words.

Pastor Jess Moody said this about comfort: “Have you ever taken a real trip down inside the broken heart of a friend? To feel the sob of the soul – the raw, red crucible of emotional agony? To have this become almost as much yours as that of your soul-crushed neighbor? Then, to sit down with him – and silently weep? This is the beginning of compassion.”

We continually come in contact with people who are hurting. Let’s minister grace and healing to them through the simple but effective gift of comfort.