Problem: Nothing was more sacred aboard a ship than respecting the chain of command. On a ship, the captain reigns supreme. — Slade

Solution: In industries in which human error can lead to devastating consequences, it’s important to foster good communication that respects the hierarchy while allowing room for debate. No one makes a decision in a vacuum. — Slade

In her book, Into the Raging Sea, Rachel Slade describes the events leading up to the sinking of the container ship El Faro in 2015. It was the largest U.S. maritime accident since World War II. The incompetent and egotistical captain, Michael Davidson, steered the ship directly into the eye of Hurricane Joaquin. Thirty foot waves and 120-mph winds sank the ship and all 33 crew members died. The recovered black box had recorded 26 hours of conversation on the navigation bridge leading up to the sinking. The audio recording revealed that every officer and many of the crew on board knew the captain was making a fatal mistake, but no one spoke up because in maritime culture it is unacceptable to challenge a captain’s decisions. It is inappropriate to speak truth to power.

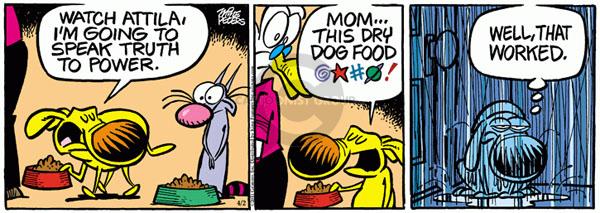

It takes extreme courage to speak truth to power. Even for those who possess solid emotional fortitude, it can be challenging and uncomfortable. It can also be hazardous to your reputation and livelihood. Rarely does someone in authority seek out voices of opposition and when those voices speak without invitation or permission, they are often sanctioned. If the issues are major and the stakes high, it’s wise to have a back-up plan in case “power” overreacts.

To be balanced and fair, sometimes the “truth-speaker” is misguided or uninformed, has an agenda to advance, or has impure motives for challenging authority. But more times than not, authority’s intimidation silences sound input.

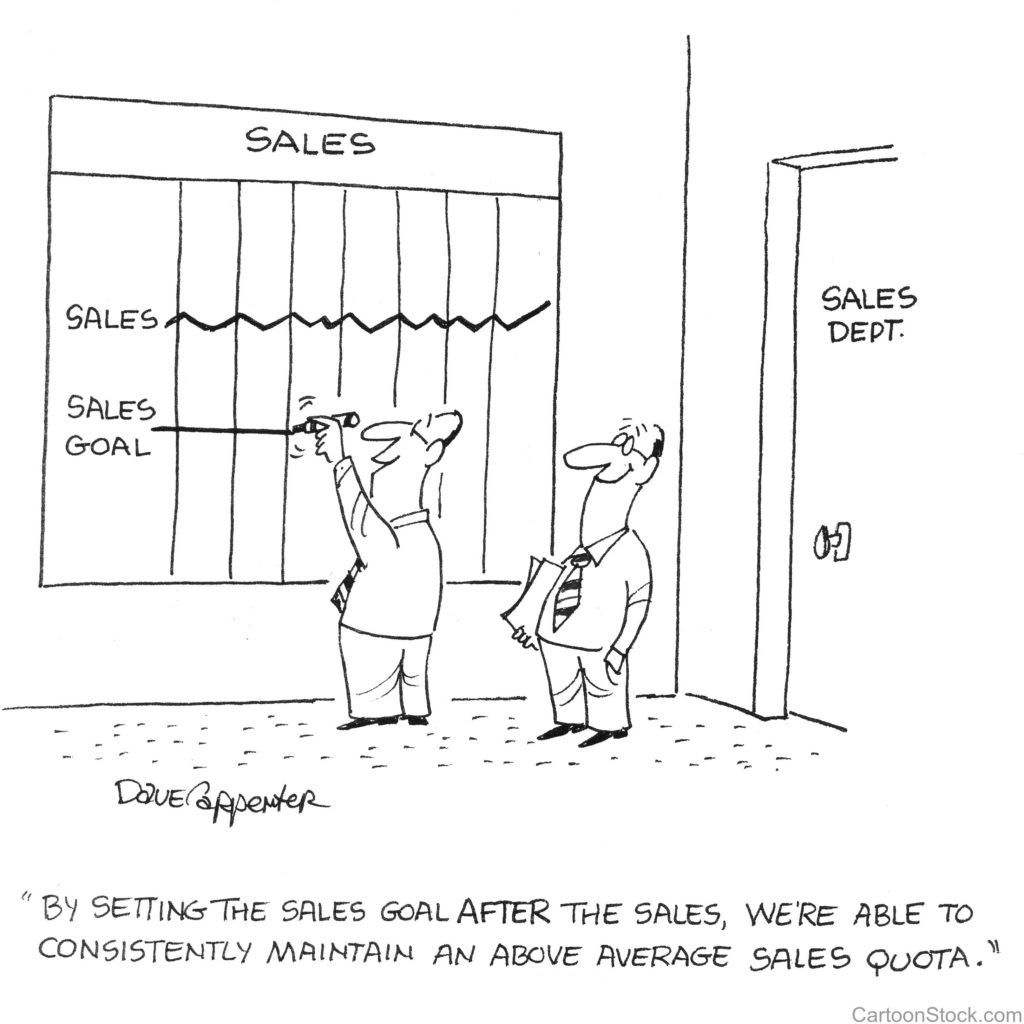

Twenty five years ago I served on staff at a church where the former pastor had led the church to build a 7,000-seat auditorium (the old sanctuary seated 1,100), and the church went from being debt-free to paying $50,000 per week in interest on the new loan. Interestingly, God “called the pastor into evangelism” several months before the building project was finished.

How did this happen? Why didn’t businesspersons in the church speak up when they saw the impending train wreck? Two issues were responsible: he was a very charismatic person who could easily beguile people, and there were no checks and balances built into the governance of the church. Surely someone had doubts, but no one spoke truth to power. We (newly appointed staff members) were tasked with cleaning up the mess, which was virtually impossible.

The antidote to this toxic social disorder is continuous robust discussion. When robust discussion is part of the culture, unilateral mistakes are seldom made. But in its absence, someone needs to speak up.

I’ll end with a story that illustrates the power of open and unfiltered conversation.

In the 1980s Delta Air Lines suffered a series of embarrassing incidents involving pilot error. “We didn’t kill anyone,” said Jack Maher, then-head of pilot training, “but we’d had pilots get lost, landing at the wrong airports.” The incidents almost always could be traced back to a bad decision made by a Delta captain.

They hired psychologist Amos Tversky to help solve the problem. Amos told them, “You’re not going to change people’s decision making under duress. You aren’t going to stop pilots from making these mental errors.” He suggested that Delta change its decision-making environments. At that time, the cockpit culture of a commercial airliner did not encourage crew members to point out the mental errors of the man in charge. The way to stop the captain from landing the plane in the wrong airport, Tversky insisted, was to train others in the cockpit to question his judgment.

Mayer said, “We changed the culture in the cockpit and the autocratic jerk became no longer acceptable. Those mistakes haven’t happened since” [from The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis, page 317].

When done appropriately and respectfully, I see little downside to speaking truth to power.