The American Psychological Association defines fundamental attribution error (FAE) as the tendency to overestimate the relationship between people’s behavior and their character and underestimate the relationship between their behavior and their circumstances. It also suggests that when we judge ourselves we tend to do the opposite: we underestimate the role that character plays and overestimate the influence of circumstances.

When someone else messes up we are quick to judge him and attribute his problem to something wrong with his character; we tend to think that people do bad things because they are bad people. But when we look at ourselves in the same situation, rather than blame our character, we consider our circumstances.

For instance, imagine you’re driving down the road when a reckless driver cuts you off and speeds forward, barely missing several other cars. You immediately think he’s a jerk, has anger problems, or may be inebriated; you assume his bad behavior is due to poor character. But if you knew that the driver has an injured person in the backseat and is rushing to the hospital, your judgment is informed by his circumstances, and you judge him differently.

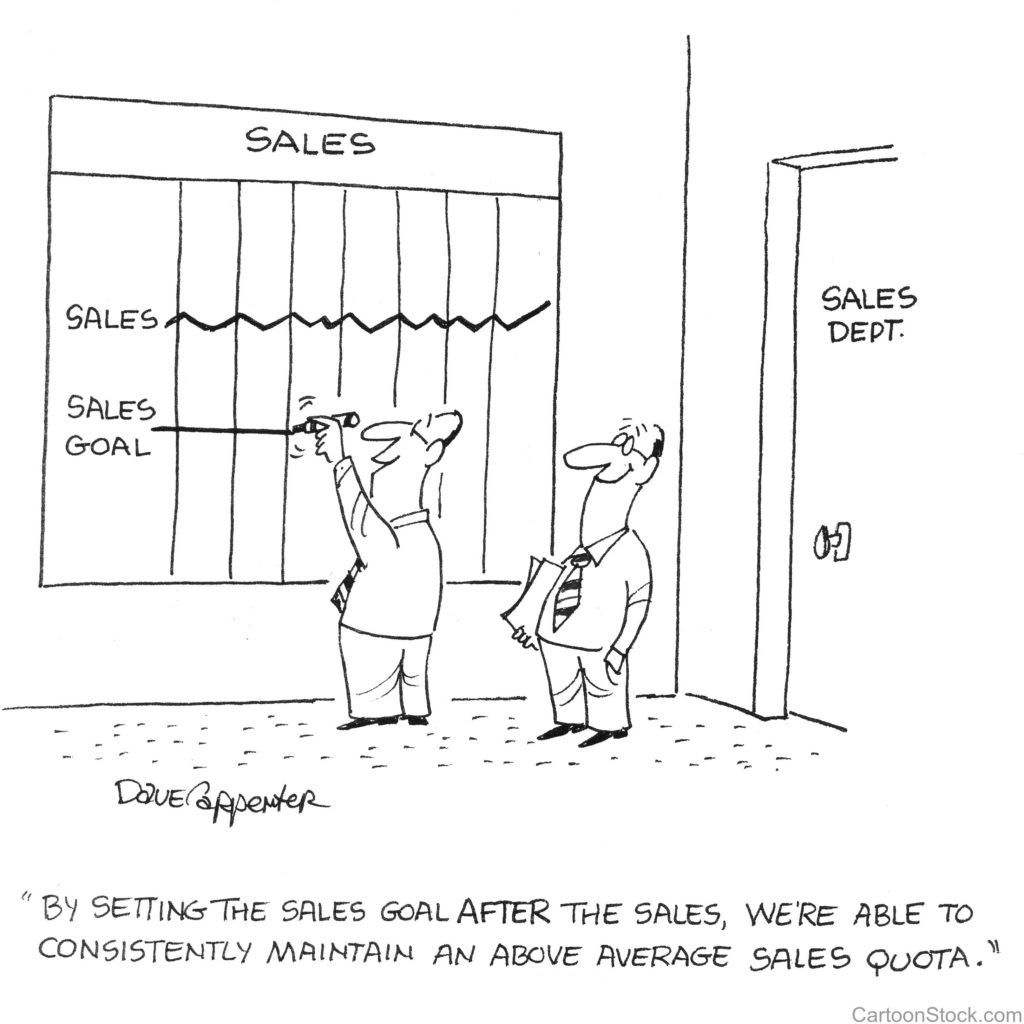

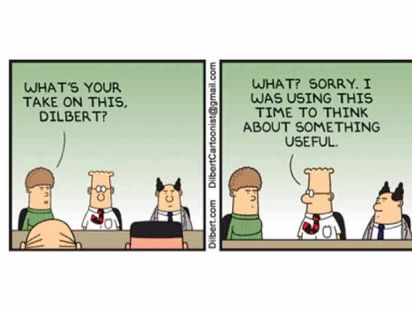

When a colleague is late to a meeting we tend to label it as a character flaw (he’s inconsiderate, disorganized, self-absorbed); but when we’re late to a meeting, we justify it based on circumstances (our previous meeting ran late, traffic is bad, we had to finish a conversation with a customer). We tend to cut ourselves slack while holding others 100% accountable for their actions.

Sometimes behavior is linked to character and sometimes behavior is linked to circumstances. FAE simply suggests that when judging other people, we have a cognitive bias—we default to the behavior/character link and when we judge ourselves we favor the behavior/circumstances link.

To correct for this error it’s helpful to invent a story that creates a positive explanation for people’s behavior. For instance, the next time someone cuts you off in traffic, think: “I hope he makes it to the hospital in time.” When someone doesn’t return your call, instead of thinking “He’s an inconsiderate jerk” think of some good reasons why he hasn’t called you back: perhaps he’s struggling with a major life-issue, or traveling for work, or he honestly just forgot to return your call.

We should presume benevolence toward others; we should choose to imagine a noble intent.

We need to give each other a break.

Here’s a short video on the subject created by the UT Austin McCombs School of Business.

I have big plans for my five-year-old grandson, Benjamin. Last summer I taught him to swim. We’re working on the alphabet, math, spatial recognition, emotional intelligence, memory, and other subjects.

I have big plans for my five-year-old grandson, Benjamin. Last summer I taught him to swim. We’re working on the alphabet, math, spatial recognition, emotional intelligence, memory, and other subjects.