All of us are smarter than one of us—unless you’re dealing with an issue that “all of us” know little or nothing about and “one of us” knows a lot. Sloman and Fernbach

All of us are smarter than one of us—unless you’re dealing with an issue that “all of us” know little or nothing about and “one of us” knows a lot. Sloman and Fernbach

One of my favorite leadership mantras is: All of us are smarter than one of us. Particularly in the complex world in which we live, no one person is smart enough to lead unilaterally. That’s why a collaborative leadership style works better than a Lone Ranger mentality. Leaders should build a diverse team of informed, committed members and then engage them when making major decisions.

But sometimes, all of us are not smarter than one of us.

Here’s an extreme, hypothetical situation that illustrates the point. Imagine five professionals (lawyer, accountant, business executive, professor, and engineer) sitting around a table, discussing a particular issue, trying to discern the best thing to do. But the decision involves a medical issue. In walks a physician, and suddenly, “one of us is smarter than all of us.” Granted, there’s a lot of brain-power in the group of five, but they’re all uninformed relative to the topic at hand.

Here’s an actual example. Years ago I was part of a group at work that interviewed candidates for a position we needed to fill. Everyone in the group was intelligent, but none of us knew anything about interviewing techniques, HR practices, tests that are available to evaluate candidates’ abilities, or the intricacies of developing a balanced and diverse team. Some of us were not even particularly insightful individuals. Together, we made a unanimous but wrong decision.

Now think back to the hypothetical case in which the five professionals are tasked with making a medical decision, but this time, the five people include an oncologist, cardiologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and a psychiatrist. That group will probably make a better decision than a single doctor would.

Granted, sometimes a diverse group is advantageous. For instance, when you’re exploring a radical idea or an entrepreneurial pursuit, it might be helpful to have an anthropologist, mathematician, artist, salesman, and a librarian brainstorm the idea. Each member of this disparate group will see the issue differently and can contribute in unique ways.

I see several factors at work here.

- The issue. What is the topic of discussion; what decision needs to be made? Are team members qualified to address this topic? If not, the team should hand off the decision to another group, or an expert “voice” should be invited into the conversation.

- The team. Are we aware of our strengths and weaknesses? Are we confident enough and have enough self-awareness to admit that we may not have the knowledge necessary to properly address an issue? Do we suffer from group-think? (Irving Janis defines groupthink as “The mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive in-group that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.”)

Having said all this, I reiterate my conviction that most leaders don’t take advantage of the wisdom of others. We act as soloists. But every idea or plan will be improved upon when submitted to the unfiltered wisdom of others. Just be sure you have the right people in the group.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

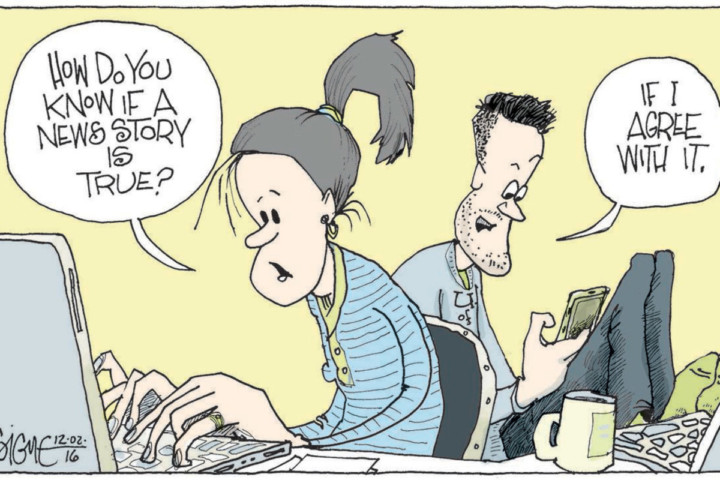

In December 2016, a screenwriter named Edgar Welch read online that Comet Ping Pong, a pizzeria in Washington D.C., was harboring young children as part of a child abuse ring led by Hillary Clinton. Welch believed the false conspiracy theory and took it upon himself to visit Comet Ping Pong, unleashing an AR-15 rifle on the workers there. By some miracle, no one was hurt and the police arrested him. He was snookered by fake news.

In December 2016, a screenwriter named Edgar Welch read online that Comet Ping Pong, a pizzeria in Washington D.C., was harboring young children as part of a child abuse ring led by Hillary Clinton. Welch believed the false conspiracy theory and took it upon himself to visit Comet Ping Pong, unleashing an AR-15 rifle on the workers there. By some miracle, no one was hurt and the police arrested him. He was snookered by fake news.

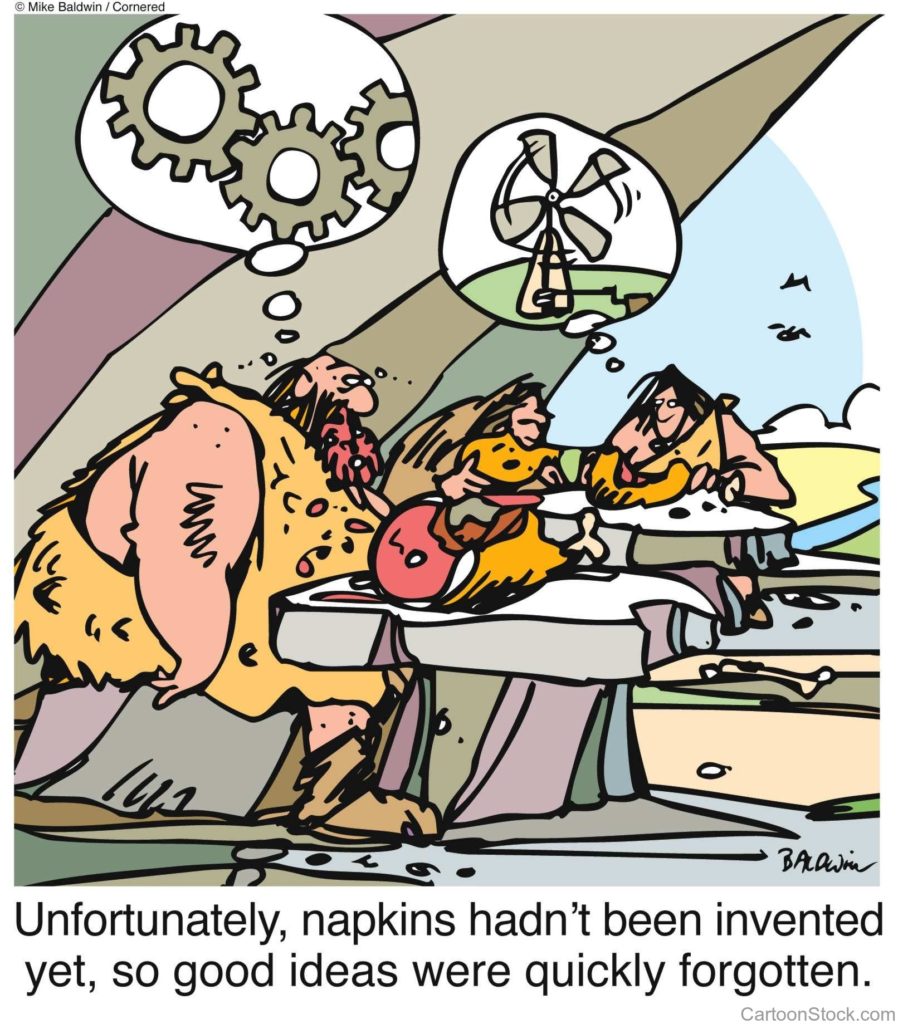

Capture good thoughts, even if you’re not sure how they might help in the future. —Andrew Hargadon

Capture good thoughts, even if you’re not sure how they might help in the future. —Andrew Hargadon