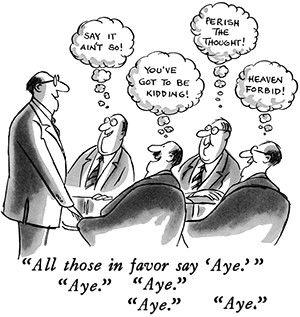

One of my favorite leadership mantras is: All of us are smarter than one of us. Get the right people in the room and let them discuss an issue or a decision that needs to be made, and their collective wisdom will exceed the wisdom of any one individual. Imagine the difference between one person taking an IQ test and the same test being answered by a group of intelligent people. The group will usually prevail.

When intelligent, informed, and engaged people meet to discuss important issues (in board meetings, weekly staff meetings, casual conversations), how can we best tap into the collective intelligence of the group?

Two ground rules will help: Encourage people to speak candidly, and insist that everyone vocalize their thoughts.

The first rule—the freedom to be truthful and straightforward—should be part of the culture of your group. It should be the default setting. Robust dialogue [link] will eliminate groupthink [link]. People shouldn’t have to wonder, if I speak my mind will I be excommunicated from this conversation? As a leader, how can you know if robust dialogue is an acceptable practice in your organization (or in casual conversations)? That’s easy to assess: If it’s not happening, it’s not deemed acceptable.

The second rule—everyone contributes to the conversation—simply means that every person should speak.

Sometimes, in a group discussion:

-

- The first person to speak sets the tone and direction of the conversation.

- The person who speaks the longest may overly influence the discussion.

- Someone who has a winsome personality or is overly passionate about her opinion may inordinately sway others.

- The person who has tenure or is the eldest member of the group may have a disproportionate impact.

- Some people may be hesitant to express thoughts that are different from the perceived consensus.

- Some people may not be mentally engaged in the conversation. They’re being mentally lazy, letting others wrestle with the issue.

The antidote to these hurdles is for everyone to vocalize his or her thoughts. For instance, if there are eight people in the meeting, eight different voices should be heard. And I’m suggesting more than just giving everyone permission to speak; insist that everyone speaks. If someone prefers not to, it’s okay for him to pass, but he needs to verbalize that preference.

These two provisos will increase the likelihood that the wisdom of the group will prevail.

Book – The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis. Forty years ago, Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky wrote a series of breathtakingly original papers that invented the field of behavioral economics. They had one of the greatest partnerships in the history of science. In The Undoing Project, Lewis shows how their Nobel Prize–winning theory of the mind altered our perception of reality. The last page made me weep.

Book – The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis. Forty years ago, Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky wrote a series of breathtakingly original papers that invented the field of behavioral economics. They had one of the greatest partnerships in the history of science. In The Undoing Project, Lewis shows how their Nobel Prize–winning theory of the mind altered our perception of reality. The last page made me weep. – In December I took my family on our 6th consecutive transatlantic

– In December I took my family on our 6th consecutive transatlantic nce of the Messiah at my church in Austin, Texas. Here are

nce of the Messiah at my church in Austin, Texas. Here are

ears. They are realtors in the Dallas metroplex. Last year they went the second mile in helping us negotiate a difficult real estate deal. Thanks, Scott and Barbara. If you need a realtor in the DFW area, they are among the best (

ears. They are realtors in the Dallas metroplex. Last year they went the second mile in helping us negotiate a difficult real estate deal. Thanks, Scott and Barbara. If you need a realtor in the DFW area, they are among the best (

Hobby update – In spring 2017 I planted a small vineyard in East Texas. I’m growing Tempranillo, Blanc-du-Bois and Black Spanish grapes. The first two years, the fruit is cut off to channel all energy to the root-system. In July 2020 I’ll be crushing grapes.

Hobby update – In spring 2017 I planted a small vineyard in East Texas. I’m growing Tempranillo, Blanc-du-Bois and Black Spanish grapes. The first two years, the fruit is cut off to channel all energy to the root-system. In July 2020 I’ll be crushing grapes. In memoriam – The day after Thanksgiving, Grams passed from this life to the next. Mary’s mother was 95-years old.

In memoriam – The day after Thanksgiving, Grams passed from this life to the next. Mary’s mother was 95-years old.