I define individual capacity as the maximum amount of productivity that a person can do and/or negotiate in a given period of time. Though we all have 24 hours in a day to produce, we each differ in how much work we’re able to complete. Some people can only keep “two plates spinning simultaneously,” others can negotiate four spinning plates, and others even more.

I define individual capacity as the maximum amount of productivity that a person can do and/or negotiate in a given period of time. Though we all have 24 hours in a day to produce, we each differ in how much work we’re able to complete. Some people can only keep “two plates spinning simultaneously,” others can negotiate four spinning plates, and others even more.

Every person has his or her personal capacity level and that level can can be increased.

Business consultant Robert Schaffer challenges us by saying: “Join me in testing the view that most companies are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity, and that the much higher levels of performance reached in emergencies are actually closer to true, sustainable potentials than are the ‘normal’ levels of performance.”

In Schaffer’s sentence, let’s substitute the word “individual” for “companies”: “Join me in testing the view that most individuals are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity.”

Twenty-five years ago I worked with a man who could spin ten plates simultaneously, but at that point in my life, I could only keep three or four plates spinning. When I compared my productivity to his, I often felt inadequate and intimidated (which stemmed from my own insecurity, not anything he said or did). But through the years I worked on increasing my capacity and now I can keep ten plates spinning.

Capacity is a function that can be increased. It is a natural part of maturation (a child’s capacity increases with age). A good goal in life is to continually increase your capacity. While there is a theoretical maximum, I doubt if any of us will reach it.

Every organization also has a capacity level. Its baseline may be determined by resources (time, money, ideas, physical resources, etc.) but ultimately it is governed by human resources, primarily leadership.

Having said all that, the main point I want to make in this essay is: leaders, don’t let your personal capacity limit the capacity of your organization.

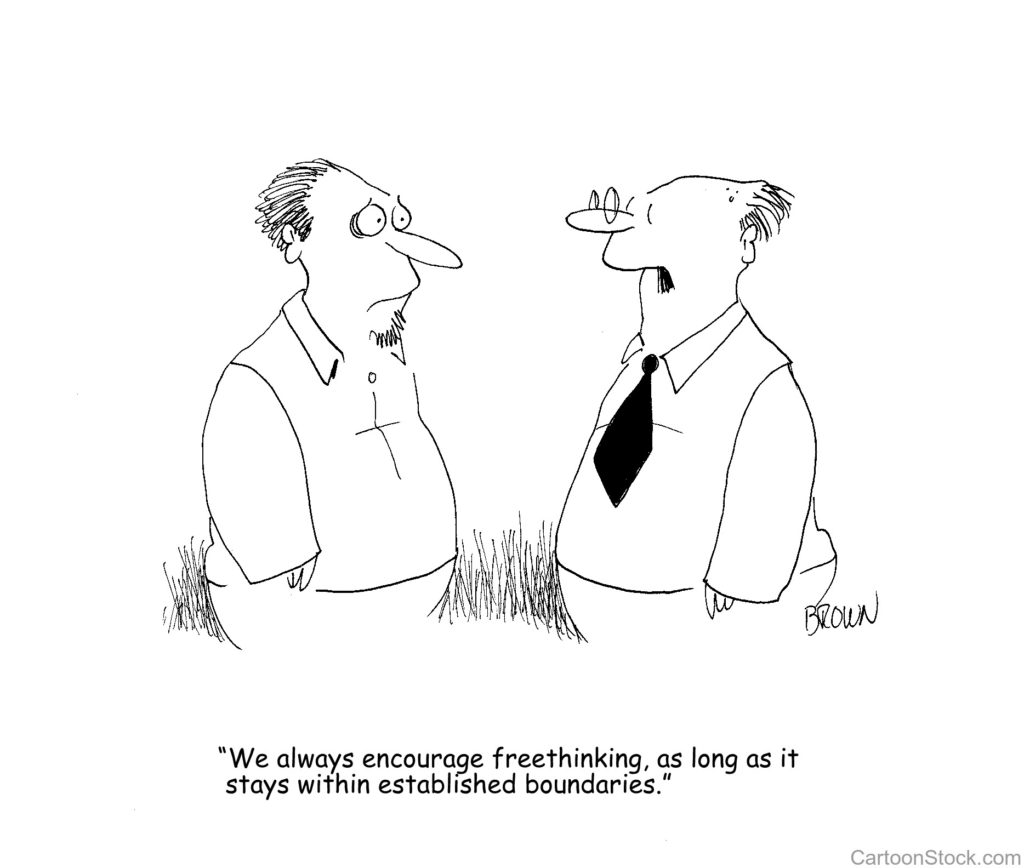

(I know I’m extending this metaphor to the breaking point, but…) if you’re only able to negotiate four spinning plates, don’t project that limit onto your organization; it’s probably capable of much more. Don’t crimp your organization’s potential by funneling everything through your personal capacity level. In fact, good leaders do the opposite-they encourage their team members and organization to achieve increasing levels of production. Instead of functioning as a governor they serve as an enabler.

The very essence of good leadership is leveraging human resources. Strategic delegation can unleash fettered resources and capacity. Challenge and empower others and your organization will grow.

Sometimes, the roles are reversed: a leader’s capacity exceeds that of the organization and its individuals. In which case the leader can carefully and gradually increase the organization’s capacity.

The growth of an organization should never be constrained by any one person.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

[callout]I’m hosting a trip to Peru, May 6-15, 2020. It will be limited to 50 travelers. Here’s the brochure. On Saturday, May 18, 2019 from 4:00-5:00, I’m hosting a free information meeting for anyone who wants more details about the trip. It will be held in the DFW metroplex and broadcast live on Facebook for those who live elsewhere. If you want to attend, email me at [email protected] or respond to this blot post.[/callout]

Every December, Mary and I spend seven days on the Queen Mary 2, traversing the North Atlantic from London to New York. It is an incredible experience; I want to be on that exact trip every year until I die.

Every December, Mary and I spend seven days on the Queen Mary 2, traversing the North Atlantic from London to New York. It is an incredible experience; I want to be on that exact trip every year until I die.

On May 6, 1954, middle-distance athlete Roger Bannister ran the first sub-four-minute mile in recorded history. The 25-year-old native of Harrow on the Hill, England, completed the distance in 3:59.4 at Oxford. At the end of the year, Bannister retired from running to pursue his medical studies. He later became a neurologist.

On May 6, 1954, middle-distance athlete Roger Bannister ran the first sub-four-minute mile in recorded history. The 25-year-old native of Harrow on the Hill, England, completed the distance in 3:59.4 at Oxford. At the end of the year, Bannister retired from running to pursue his medical studies. He later became a neurologist.