If someone had given you a horse in 1915 you would have been ecstatic. Horses were the primary means of transportation and were used extensively in agriculture. There were 26 million horses in America; one horse to every four people. The average annual salary was $680; horses sold for around $100. No wonder there were severe penalties for stealing horses.

If someone had given you a horse in 1915 you would have been ecstatic. Horses were the primary means of transportation and were used extensively in agriculture. There were 26 million horses in America; one horse to every four people. The average annual salary was $680; horses sold for around $100. No wonder there were severe penalties for stealing horses.

Before the mechanization of agriculture and transportation, horses were indispensable.

But if someone tried to give you a horse today, you’d graciously decline. Because, what would you do with a horse? Where would you put it? How much would it cost to feed it? Who would take care of it? Why bother?

But let’s not just talk about horses. Let’s talk about furniture, clothes, cars, and other stuff. Most items depreciate in value as soon as they are purchased. When they become unnecessary, outdated, or broken they become a burden.

Do we really need so much stuff?

I once read of a nomadic tribe in Africa whose members refuse to accept gifts because if they accept a gift they’ll have to carry it wherever they go for the rest of their lives. That might be a good standard by which we should judge the wisdom of buying something: Do I really want to be responsible for this thing for the rest of my life?

Before you buy something, ask yourself “Two years from now, will I be glad I bought this item? How about 10 years from now?” Also ask, “Will I have to paint it? Change the oil in it? Find space for it? Worry about it? Will it be used? Is it merely a status symbol? Who initiated this conversation? Have I seriously considered the pros and cons of owning this thing? Am I yielding to consumerism, materialism, or vanity? Will this object distract me from more important life-issues?”

Many years ago I committed to live with 100 or fewer possessions. The decision has simplified my life and allowed me to focus on more important issues.

The artist and philanthropist John Ruskin once said, “Every increased possession loads us with a new weariness.” Let’s get rid of the horses.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

[callout]Bill Gates calls Hans Rosling’s bestseller, Factfulness, “one of the most important books I’ve ever read–an indispensable guide to thinking clearly about the world.” Gates is so impressed with the book that he is giving an online copy to every college graduate in the United States.

I read the book last week and I’m equally impressed. Rosling discusses eight fallacies that lead us to misinterpret the world. Here are three of the eight:

- The gap instinct: we tend to focus on extremes rather than on the large majority in the middle.

- The negativity instinct: information about bad events is far more likely to reach us than good news.

- The straight-line instinct: we tend to assume that current trends will continue as they are.[/callout]

There are four major chemicals in your brain that influence how happy you are. Our bodies produce these chemicals naturally, but in some people, the body doesn’t produce enough. This deficiency can make us sad, anxious, negative, hopeless, and depressed.

There are four major chemicals in your brain that influence how happy you are. Our bodies produce these chemicals naturally, but in some people, the body doesn’t produce enough. This deficiency can make us sad, anxious, negative, hopeless, and depressed. We are reluctant to say them, but when spoken honestly and appropriately, three simple phrases can help maintain our personal integrity and sustain peace in relationships.

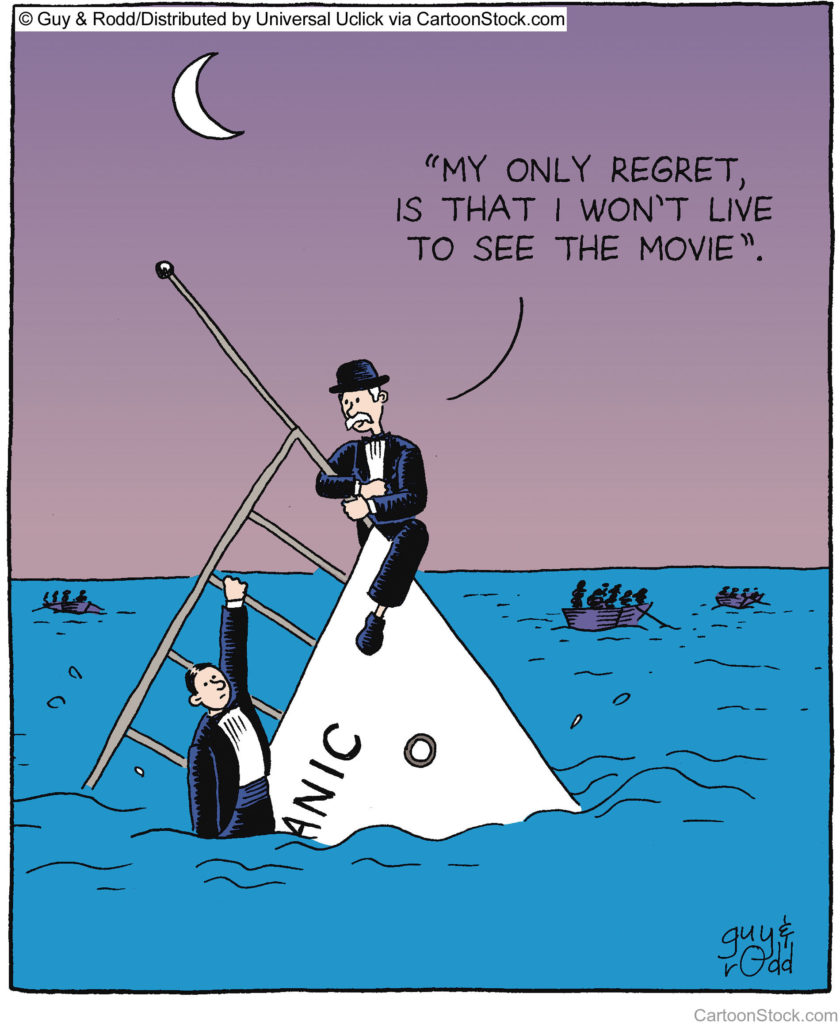

We are reluctant to say them, but when spoken honestly and appropriately, three simple phrases can help maintain our personal integrity and sustain peace in relationships. At the beginning of each new year we’re encouraged to set goals for the coming year. I’m a big fan of that. It might also be beneficial to periodically list regrets: things we regret about the previous year and even regrets from the distant past that have come into focus.

At the beginning of each new year we’re encouraged to set goals for the coming year. I’m a big fan of that. It might also be beneficial to periodically list regrets: things we regret about the previous year and even regrets from the distant past that have come into focus.