I recently attended a professional conference that was planned and hosted by a friend. Halfway through the conference, I saw him in the hallway and he asked me how I thought the conference was going. I said I was enjoying it, but then I added, “I do wish the sessions would start on time; and, it would be helpful to have a center aisle in the main meeting area.”

I recently attended a professional conference that was planned and hosted by a friend. Halfway through the conference, I saw him in the hallway and he asked me how I thought the conference was going. I said I was enjoying it, but then I added, “I do wish the sessions would start on time; and, it would be helpful to have a center aisle in the main meeting area.”

While both comments were true, they were unnecessary and inappropriate. I was 94% pleased with the conference but my friend probably walked away from our conversation remembering my negative comments. It wasn’t my place to micro-critique; his team would do that at the right time. I regret speaking those words.

Most unsolicited advice and critique is unappreciated and unproductive. Even when it is requested we need to be careful as to when and how we speak. To some degree, we’re all thin-skinned and sensitive to criticism and review.

Consider:

- In any given situation, is it your responsibility or right to offer advice and critique? Just having an opinion is no justification for expressing it.

- When you do have the right to offer advice and critique, consider the proper timing. For example, suppose your child just played a violin recital and the family has just gotten in the car. Is this the right time and place to say, “You played out of tune; you should have been better prepared”? (This example comes from personal experience, I’m ashamed to say.)

- Following all events, schedule a debriefing meeting at which time the event will be analyzed. (“Our workshop is this Saturday. Let’s meet next Tuesday morning to analyze and critique the event.”) Both observers of the event and those who actually performed can anticipate having a fair, thorough, and productive examination of what took place.

I am a huge advocate of analyzing everything; all products, services, events…everything. Just be sensitive to when and how you do it.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay.[/reminder]

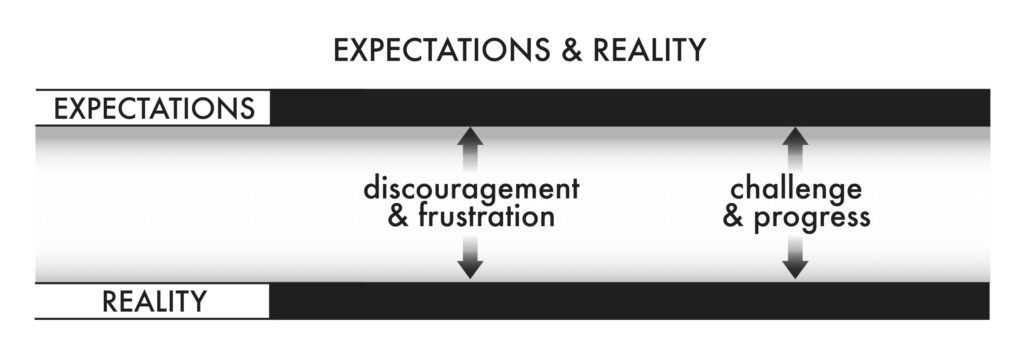

For years, I had unrealistic expectations regarding a close friend. I was continually frustrated and he was constantly discouraged because of the unrealistic gap between expectations and reality. It was my faulty judgment that was causing the strain and friction in our relationship. When, in my mind, I “lowered the bar” closer to reality, my frustration subsided and the relationship improved.

For years, I had unrealistic expectations regarding a close friend. I was continually frustrated and he was constantly discouraged because of the unrealistic gap between expectations and reality. It was my faulty judgment that was causing the strain and friction in our relationship. When, in my mind, I “lowered the bar” closer to reality, my frustration subsided and the relationship improved. Observe and study experiences as an anthropologist would observe and study a ritualistic dance of a tribe in the Amazon.

Observe and study experiences as an anthropologist would observe and study a ritualistic dance of a tribe in the Amazon. In my high school debate class we were taught to develop a sound argument for and against each proposition. Prior to a debate we didn’t know which side of the proposition we would be asked to defend so we had to be prepared to support either side. It taught us good debating technique and a good life skill.

In my high school debate class we were taught to develop a sound argument for and against each proposition. Prior to a debate we didn’t know which side of the proposition we would be asked to defend so we had to be prepared to support either side. It taught us good debating technique and a good life skill.