Genba (現場, also romanized as gemba) is a Japanese term meaning “the real place.”

Japanese detectives call the crime scene genba. Japanese TV reporters may say they are reporting from genba. In business, genba refers to the place where value is created; in manufacturing the genba is the factory floor. [Wikipedia]

Genba is where action happens. Being there is advantageous. At the genba we see and sense things that might be missed from a distance.

For instance, when my daughter, Lauren, and her family were moving from Florida to Dallas, Lauren made a preliminary trip to find a good middle school for her daughter, Marin.

The long-range goal was to get Marin into Dallas’ TAG School (talented and gifted), which U.S. News and World Reports consistently ranks as the #1 public high school in America. There are several DISD middle schools that feed into TAG, so the chances of getting into the elite school is enhanced by being a student at one of the feeder schools. But the acceptance rate is low. When Lauren visited, school was about to start.

During her trip, Lauren insisted on visiting Dealy school (one of the feeder schools). I suggested that we simply call the school and talk to someone, but Lauren wanted boots on ground, so we went to the genba. Although we didn’t have any appointments, Lauren – in her typical kind and determined manner – negotiated a meeting with the principal and several key teachers.

During the conversations we discovered that the entrance application was due the next day, and the only way to apply at that late date was to do so in person at the DISD headquarters in downtown Dallas. We made the trip downtown (another genba), and completed the application. In the following weeks Lauren continued to communicate with the teachers and administrators she had personally met at Dealy.

To make a long story short, Marin was accepted into Dealy and, two years later, into TAG.

I really don’t think these good things would have happened unless Lauren had insisted on visiting the physical campus – the real place.

Here’s a hard-to-believe example of someone not visiting a genba. In my undergraduate studies at U.T. Austin, my German teacher was a young man who was finishing his Ph.D. in German studies. I was shocked to learn that he had never visited Germany; he had never even traveled outside the United States. What was he thinking?

Visiting a genba takes extra effort and resources, but it is usually revealing and therefore rewarding. It provides a multi-sensory encounter with the place in space where something happens and we are able to see, hear, touch, taste, and smell reality.

[reminder]What are your thoughts about this essay?[/reminder]

Summary

What? – The term genba refers to the physical place where something happens.

So what? – Often, it is advantageous to visit the genba.

Now what? – As an individual, develop a curiosity about places of origin; get out of your dog-runs and explore unfamiliar places where things happen. Learn to sense when an on-site visit would be beneficial.

Leaders – As a leader, define the genbas of your organization (you have many) and visit them. Remember, genba refers to a physical place. Where are your products and services made? Where are they delivered? Who are your stakeholders, and where are they?

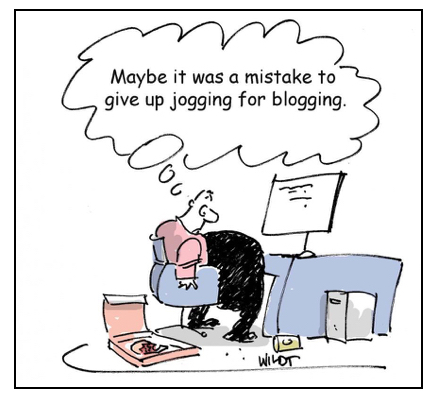

Thank you for subscribing to my blog site. I hope my posts have been beneficial. I posted my first essay on December 10, 2014 and have posted once a week for the past 52 weeks. I started with 10 subscribers, I now have 3,500+

Thank you for subscribing to my blog site. I hope my posts have been beneficial. I posted my first essay on December 10, 2014 and have posted once a week for the past 52 weeks. I started with 10 subscribers, I now have 3,500+

The hot-stove effect was first proffered by humorist Mark Twain: “We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it and stop there lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again and that is well but also she will never sit down on a cold one anymore.”

The hot-stove effect was first proffered by humorist Mark Twain: “We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it and stop there lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again and that is well but also she will never sit down on a cold one anymore.”