I have big plans for my five-year-old grandson, Benjamin. Last summer I taught him to swim. We’re working on the alphabet, math, spatial recognition, emotional intelligence, memory, and other subjects.

I have big plans for my five-year-old grandson, Benjamin. Last summer I taught him to swim. We’re working on the alphabet, math, spatial recognition, emotional intelligence, memory, and other subjects.

I’ve added a new item to the curriculum: I want to teach Benjamin how to listen. It’s a critical life-skill that some people never learn. I want him to excel at it.

Here are some basic thoughts relative to listening. I haven’t figured out how to teach these to a preschooler, but I’m going to try.

There’s a difference between hearing and listening.

Hearing is an involuntary, physiological function. Unless you’re hearing-impaired, it just happens. Just like your kidneys function without your permission, your auditory system is constantly on, so you’re hearing every moment of your life.

Listening occurs when your mind chooses to focus on a particular part of what your auditory system is receiving. Listening is active; you decide when to listen and what to listen to. It’s like a toggle switch that you can flip on or off. Of all the various sounds you’re hearing at any moment, you choose to focus on some of them and try to make sense of and find meaning in what you hear. If you choose to focus on what a person is saying, you try to garner meaning from her words and sentences.

Listening is difficult because it requires intense focus and concentration. At any moment your mind can choose to focus on stimuli from any of your five senses—what you see, feel, taste, touch, or hear—or any random thought your mind conceives of. Your thoughts can also be affected by your emotions. Even after choosing to focus on something you are hearing (as opposed to something you’re seeing, etc.) your mind can get distracted and drift.

Listening is a skill that must be developed.

Just like we’re not born with the skill to play tennis, or fly a plane—these skills must be developed—listening is a skill that must be cultivated. It’s not a natural endowment. On a scale from 1-10 (1 being we are inept at listening, 10 being we have advanced listening skills) we all start out in life at level one. Sadly, some people stay in the low digits their entire life.

It takes conscientious effort to develop a skill. A curriculum helps, as does a coach. But most of us have never taken a considered approach to developing listening skills. Our current skill level was most likely developed through trial and error and fragmented bits of instruction.

There must be a better way.

Why is listening so important?

We learn by listening.

All five of our senses are entry-ports for information and stimuli that we use to learn about our world. Indeed, they are the only source of information. Second only to seeing, listening is the primary faculty for learning. But as mentioned in the previous section, just hearing is insufficient; we must listen—focus and engage the mind—to learn.

Listening is essential for healthy relationships.

The health of all relationships (individual and corporate) rises and falls on communication, which is best expressed through dialogue, which involves both talking and listening. Productive talking is also a skill that must be developed, but listening is the more difficult of the two.

Author David Augsburger suggests that, “Being heard is so close to being loved that for the average person, they are almost indistinguishable.”

Professor Ralph Nichols wrote, “The most basic of all human needs is the need to understand and be understood. The best way to understand people is to listen to them.”

Relative to healthy dialogue, I highly value Stephen Covey’s statement, “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” First listen, then talk.

Good communication is the oil that lubricates the working parts of relationships and active listening is the foremost component.

Suggestions for improved listening

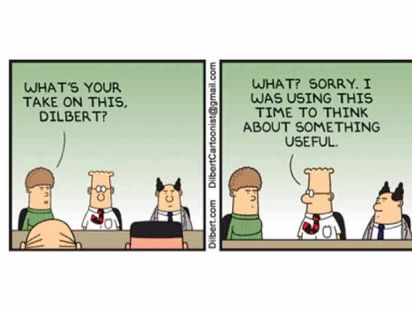

When someone is talking, focus on listening to what he is saying. Don’t spend those moments developing your response to his comments or crafting the next thing you want to add to the conversation.

Don’t interrupt. Doing so devalues the speaker and infers that what you want to say is more important.

After listening, sometimes it’s helpful to repeat to the speaker what you think was said: confirm that you understand correctly. But don’t do this mechanically or automatically or it will appear contrived and patronizing.

The best example of good listening I’ve ever seen was hearing a conversation among members of the Juilliard string quartet. Click here to read the post.

Some people listen to hear, others listen to respond.

Jackie, that is a great phrase. I’ll find a way to use it in a future post. Thanks.

Great article!. . . I especially liked the quotes from David Augsburger, Ralph Nichols, and Stephen Covey. They emphasize that listening is not just being polite. Being heard and understood is a basic human need.

The suggestion to allow for a time of silence after someone speaks, is an important one. Growing up, I was always the one to interrupt. . . of course, my thoughts were always so important!. . . . As I got older, I realized how selfish and unkind it was to not let people finish speaking. The article related to the Julliard String Quartet was especially meaningful for me. It’s a habit we should all try to practice often.

Thanks, Linda, for affirming comments and for sharing how you’ve grown in this area. We’re all on a journey toward maturity.

Excellent article as always!

My mother in law used to tell Marsha, if you won’t listen, you’ll have to feel. I think that is generally true in life as well.

Mark, I love that statement.

Thank you for this. I appreciate the information & insights.

Thanks, June, for taking the time to write.

The quartet were discussing a subject on which they all had expert knowledge. It seems that there was no competition amongst the speakers. Listening patiently becomes much more difficult when the speakers are passionate people with a range of views about the subject. Even more difficult when the same subject is coming up for the upteenth time and no action has been taken since the last occasion.

Angela, you always have keen insight to share. You’re right: amongst a homogeneous group there are less contradictions so it’s easier to listen attentively (though the conversation at times can get boring).