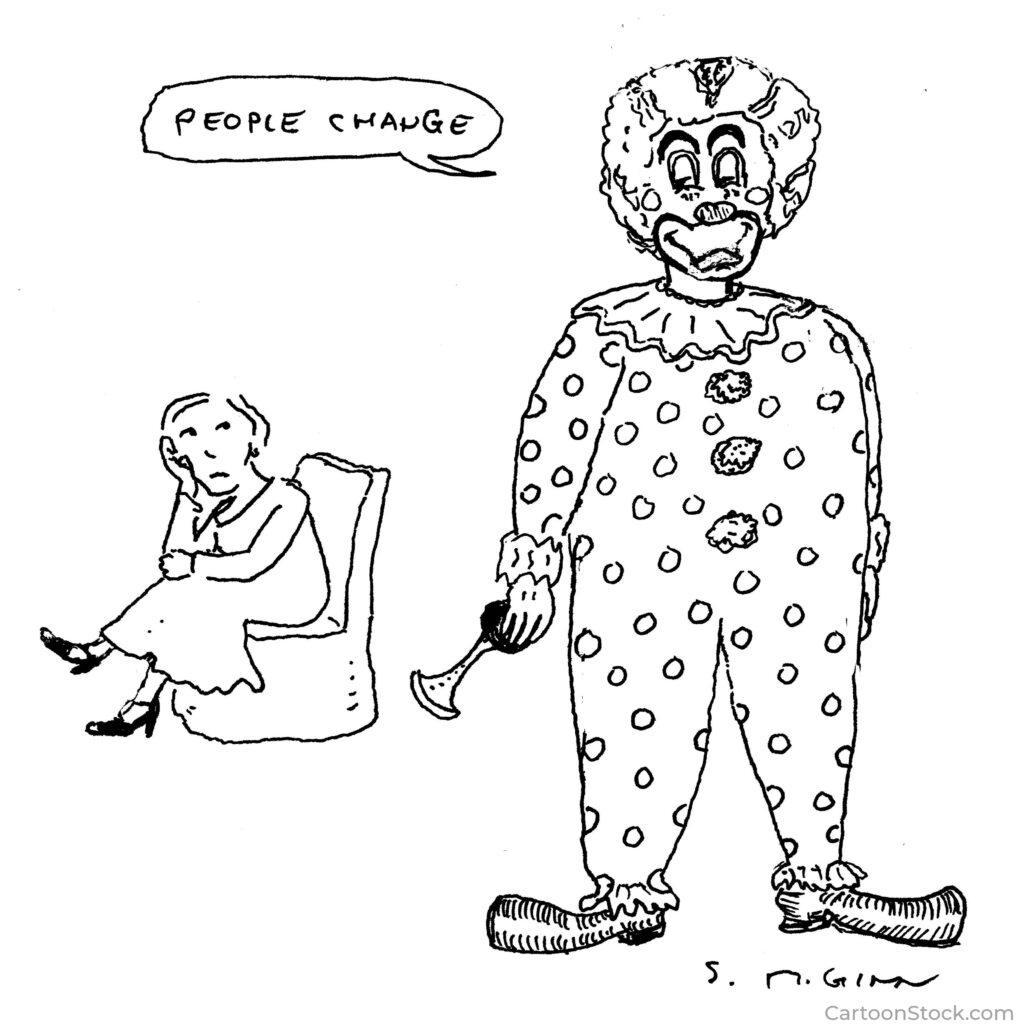

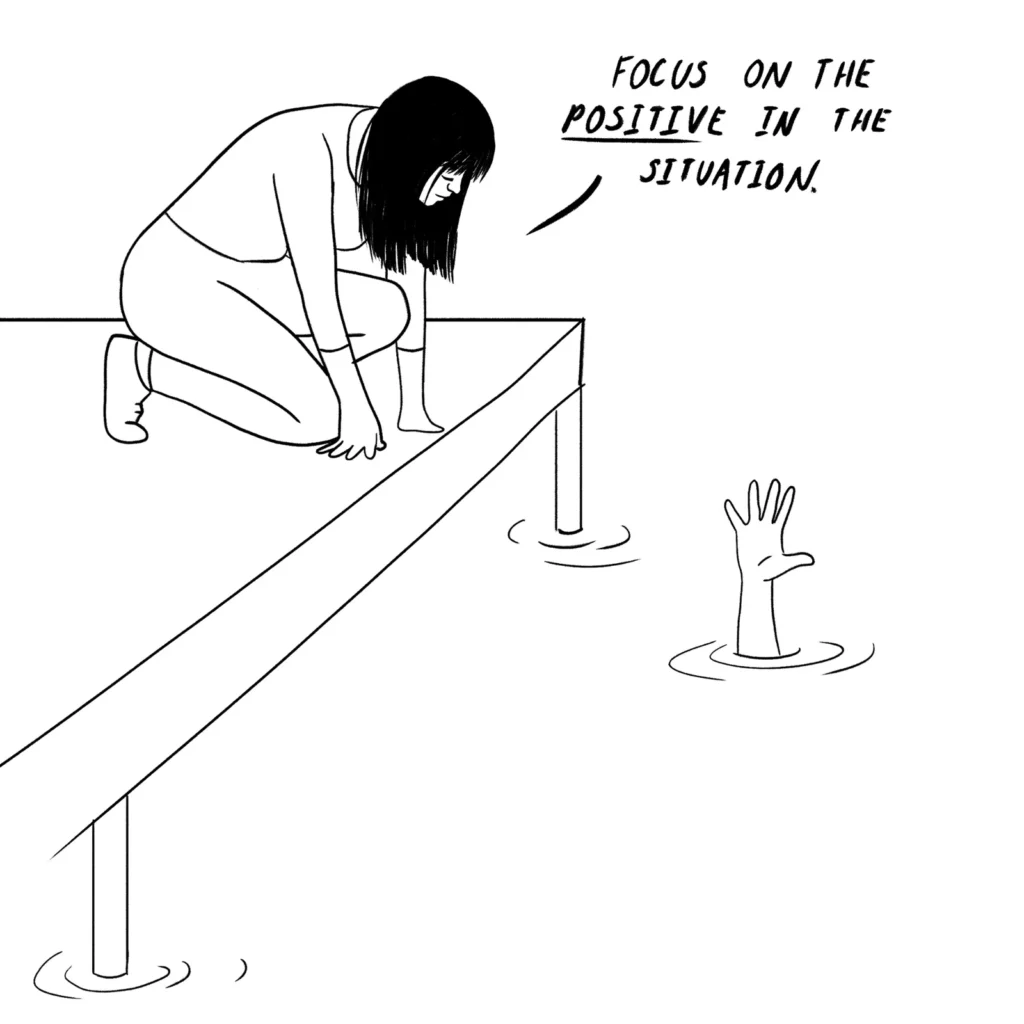

Have you ever met someone who is quick to give his opinion about how things should be done but doesn’t accomplish much himself? The bystander. The critic. Present but uninvolved. Passive but opinionated. Occasionally, his input may be beneficial, but I prefer the thoughts of people who are fully engaged in the process they’re commenting on, or at least fully engaged in something.

I do enjoy and see the benefit of, getting multiple inputs and opinions. One of my favorite leadership thoughts is “All of us are smarter than one of us.” Getting input from a lot of people on any idea or plan will improve it. But good input usually comes from engaged, active people — those who have earned a place in the conversation through involvement.

In a speech titled Man in the Arena, Theodore Roosevelt spoke of the importance of individual responsibility and involvement:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

[For a unique and interesting commentary on Roosevelt’s full speech, read Michael Cullinane’s article What celebrities get wrong about a famous Teddy Roosevelt Speech. ]