Several years ago Mary and I toured Morocco. We started in Marrakesh, then went to Fez and ended up in Casablanca, which is a really rough, dirty city. (The movie Casablanca was filmed in Hollywood, so it’s not an accurate depiction of what the city really looks and feels like).

Several years ago Mary and I toured Morocco. We started in Marrakesh, then went to Fez and ended up in Casablanca, which is a really rough, dirty city. (The movie Casablanca was filmed in Hollywood, so it’s not an accurate depiction of what the city really looks and feels like).

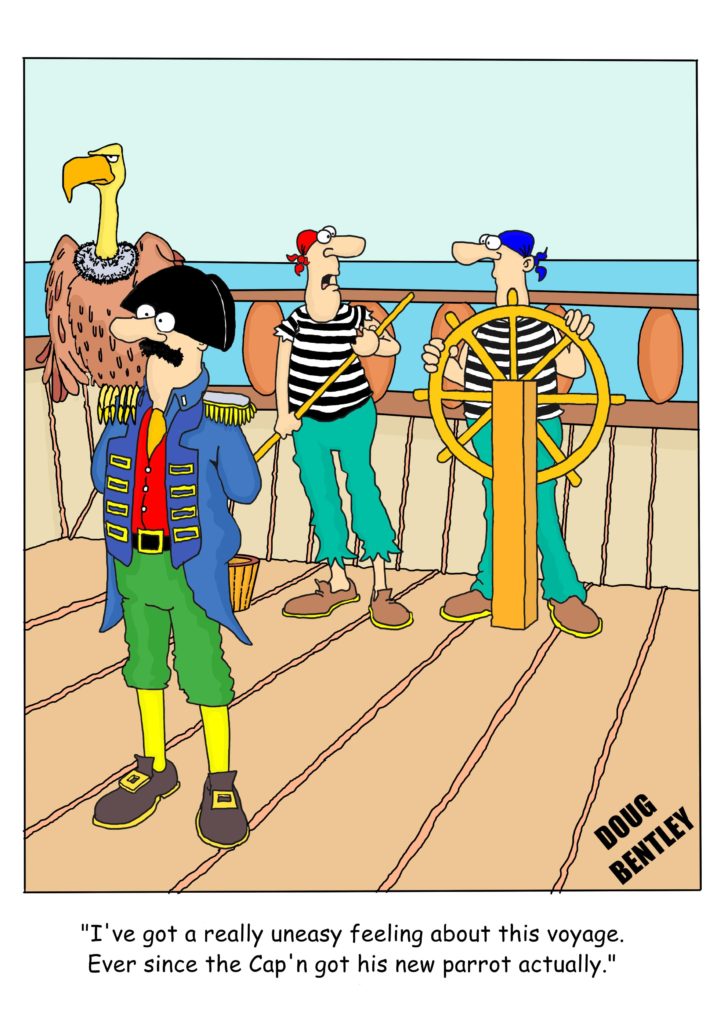

One of the must-see sites is the Hassan II Mosque; it is the largest mosque in Morocco and the 13th largest in the world. I took a taxi from my hotel to the mosque, but when the tour ended, I decided to walk back to the hotel. About a quarter mile into the two-mile route I found myself in a rough neighborhood, the slums. I’m not easily frightened but I suddenly had the overwhelming feeling that I was in the wrong place and in danger. I reversed my course, got back to a main street, and took a taxi back to the hotel.

I yielded to my unsubstantiated uneasiness and possibly avoided a bad situation.

Pilots are taught to pay careful attention to what they call “leemurs”—the vague feeling that something isn’t right, even if it’s not clear why.

At times, we should do the same.

Don’t be extreme with this suggestion. Ninety percent of the time, there is a logical explanation for feelings of uneasiness – your understanding + experience is sounding the alarm – but sometimes there’s not. That’s when we need to heed that quiet, subtle voice that’s saying, “Be careful.”

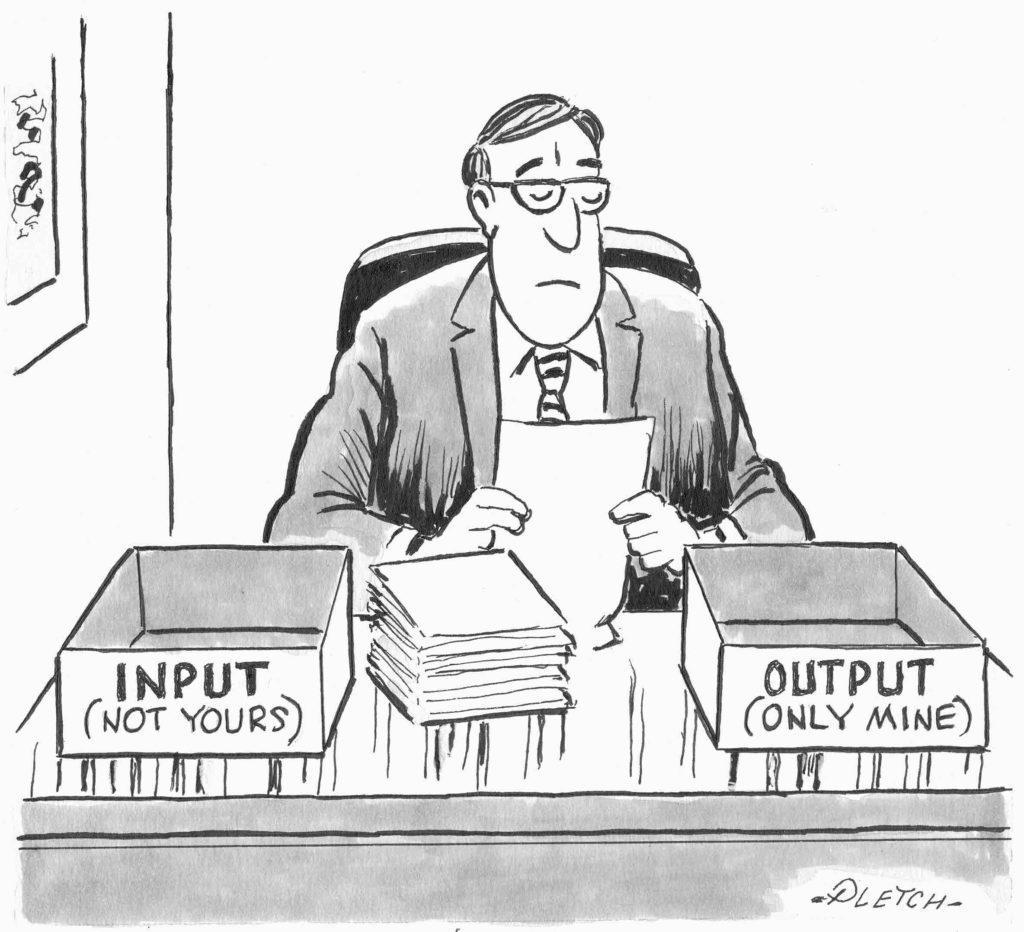

My son-in-law, who is a flight surgeon for an F16 squad and a pilot himself, tells me that in the cockpit of a military plane a lower-ranking officer can “pull rank” at any time he or she feels that the mission is going in the wrong direction. They have the authority to act on leemurs.

Leaders: Wouldn’t it be beneficial if you gave your team members permission to vocalize the leemurs they may experience in the context of the organization?

[reminder]When have you experienced leemurs? How did you respond?[/reminder]

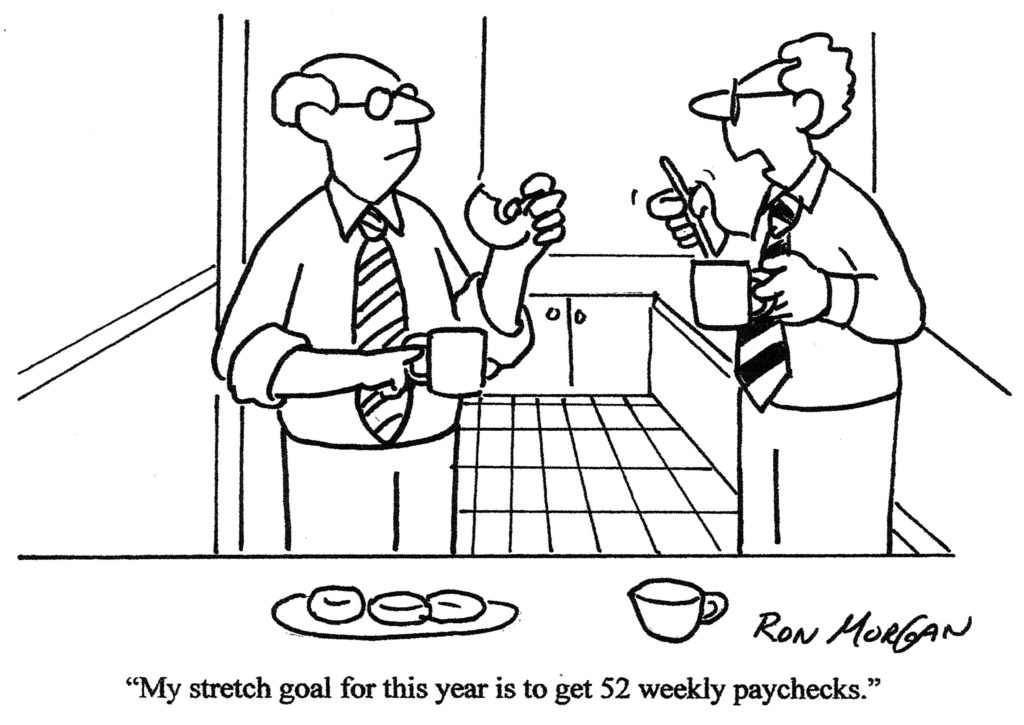

Join me in testing the view that most individuals and companies are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity, and that the much higher levels of performance reached in emergencies are actually more closer to true, sustainable potentials than are the “normal” levels of performance. Robert Schaffer

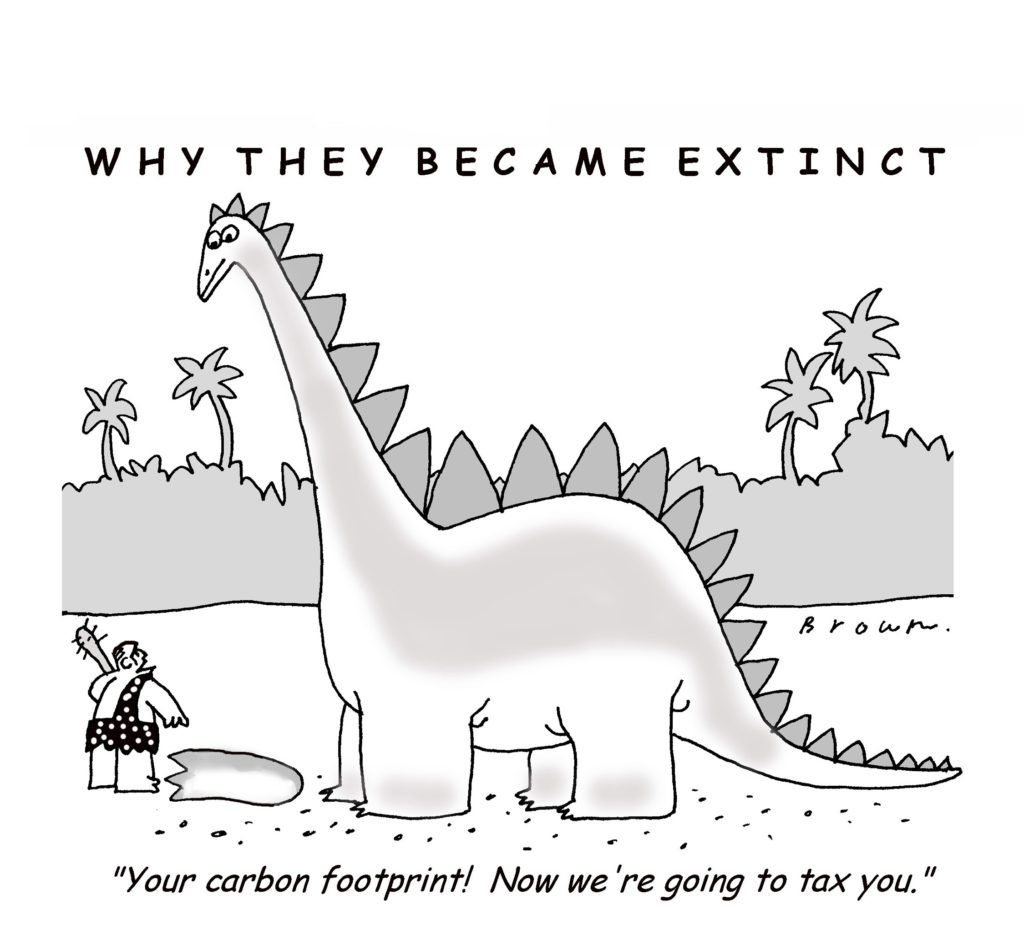

Join me in testing the view that most individuals and companies are functioning at only 40, 50, or 60 percent of their capacity, and that the much higher levels of performance reached in emergencies are actually more closer to true, sustainable potentials than are the “normal” levels of performance. Robert Schaffer Peter Drucker coined the phrase “organized abandonment” to describe the process whereby we can free up resources that are committed to maintaining things that no longer contribute to performance and no longer produce results.

Peter Drucker coined the phrase “organized abandonment” to describe the process whereby we can free up resources that are committed to maintaining things that no longer contribute to performance and no longer produce results. In the 1840s, a young obstetrician in Vienna named Semmelweis noticed that doctors who performed autopsies and then delivered babies had a high rate of disease among the children they delivered (known as childbed fever). So he made the audacious and until then, unheard of, suggestion that doctors wash their hands between doing an autopsy and delivering a baby. He recommended that they wash in a solution of chlorinated lime, which apparently solved the problem; there were fewer cases of childbed fever.

In the 1840s, a young obstetrician in Vienna named Semmelweis noticed that doctors who performed autopsies and then delivered babies had a high rate of disease among the children they delivered (known as childbed fever). So he made the audacious and until then, unheard of, suggestion that doctors wash their hands between doing an autopsy and delivering a baby. He recommended that they wash in a solution of chlorinated lime, which apparently solved the problem; there were fewer cases of childbed fever.