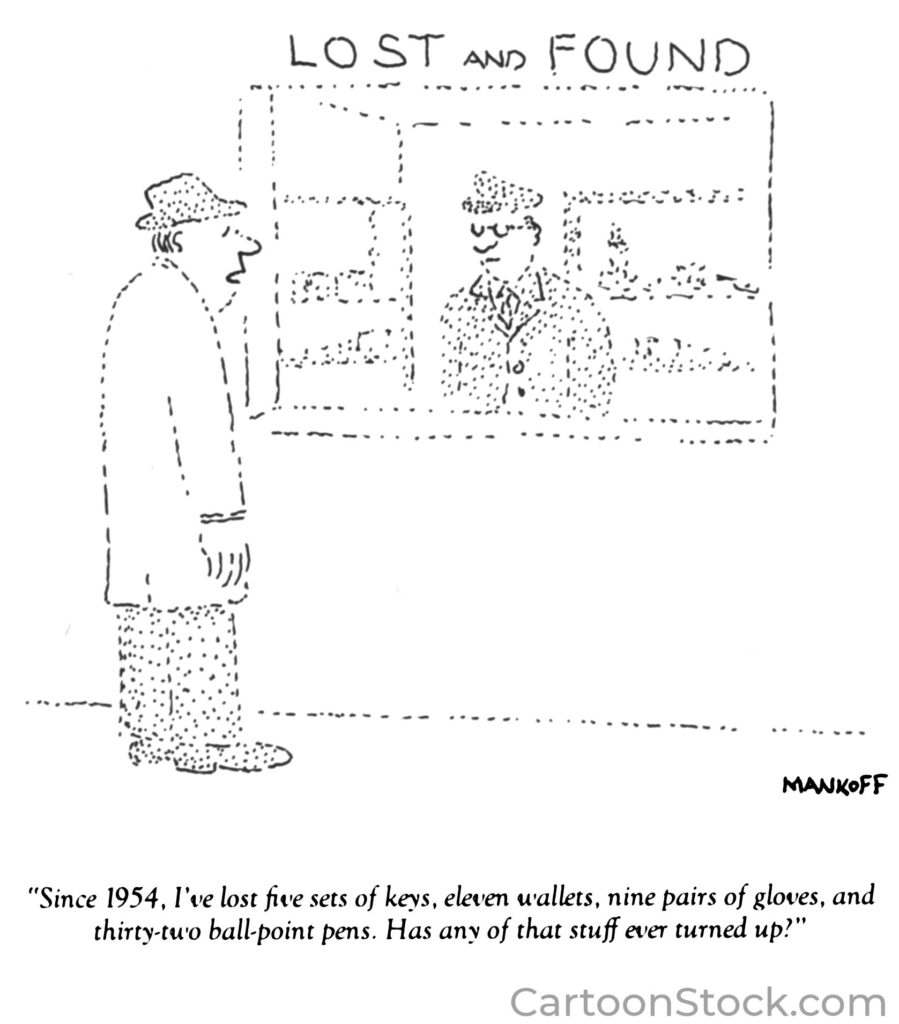

David Whyte, Anglo-Irish poet, tells a story about losing and finding his favorite pen, a Mont Blanc given to him by a friend. It is his favorite pen, not because it’s an expensive instrument, but because for decades it has been his constant companion and he uses it to write poetry and sign books.

He was on a red-eye flight returning to Belfast. Moments before the plane landed, as he started getting his belongings together, he realized he must have dropped his pen. He was sitting in first class, so his seat was not the simple, straightforward kind; it was highly mechanized and hard to access. He tried in vain to find his pen.

When all passengers were off the plane the stewardess helped him look for it, but to no avail. She finally said, “Mr. Whyte, the only thing left to do so is ask an engineer to board the plane and take the seat apart.” He gently said, “Please do.”

Twenty minutes later, with the seat torn apart, there it was…his pen.

Whyte says that from that moment on, he valued the pen even more, for it had been lost but now was found.

He uses that story to teach an important truth: Sometimes losing something and then regaining it enhances our appreciation of it. Whyte even suggests that we should periodically play a mind game with ourselves in which we “experience” the lost/found/increased-value scenario, but without having actually suffered the loss.

Try this:

- Close your eyes for a few minutes and imagine that two years ago you lost your sight. The world is now dark 24/7. Then imagine that through a medical procedure, or miracle, your sight has been restored. Now open your eyes and savor the sight of objects, people, colors, and shapes. The color red. A sunset. A loved one. You can drive a car again. You’ll have a greater appreciation for something you have taken for granted—sight.

- Imagine that you have lost someone you love: a child, friend, or spouse. Think deeply about what life would be like without him or her; feel the sadness. But then remind yourself that you haven’t lost them, it’s just a mind game.

- Imagine that you’re confined to solitary confinement. You’re in an 8×10 cell (slightly bigger than the average bathroom). You’re by yourself in the cell for 22 to 24 hours a day. When let out, it is into a small, solitary, outdoor area. But your confinement is only a daydream. With a new sense of gratitude, enjoy the rest of your day as the free person you really are.

Whenever I play this mind game, I become more grateful, less ill-tempered, more mindful and humbler, and more aware of God’s goodness and the joy of living life.