I’ve written before on the curse of knowledge

-

- Part 1 – The “curse of knowledge” may occur when someone has such mature and advanced knowledge in a specific area that he cannot remember what it’s like to not have this knowledge.

- Part 2 – It can happen when you share too much information about an area of expertise.

- Part 3 – We tend to share what we’ve recently learned, though it may not be appropriate to the current conversation.

In this post I’ll talk about yet another way that our personal knowledge can often be a hinderance in our personal relationships.

What do these scenarios have in common?

-

- Mary and I served a good California chardonnay at a dinner party we hosted for friends. Someone made a nice comment about the wine and I responded, “It is nice, but I should have served it about five degrees cooler.”

- At Sunday brunch, someone commented on how much they enjoyed the instrumental group that had played in the morning worship service. My response was, “Yes, they are a talented group. They struggled with intonation in the first service but were spot on in the second service.”

- In a staff meeting, I corrected someone’s pronunciation of a foreign term. It interrupted the flow of conversation, may have embarrassed the speaker, and made me look like a pompous backside.

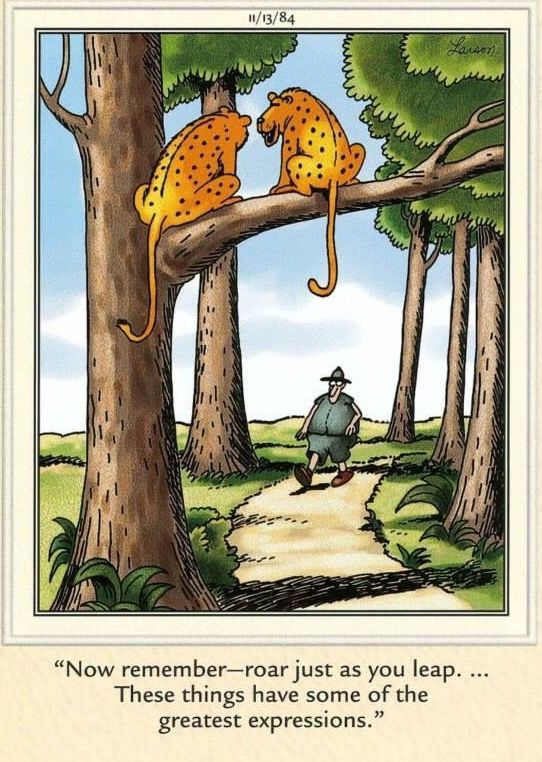

Here’s the challenge I’m talking about: When we’re knowledgeable in a certain area, we’re more likely to notice errors that are made in that domain, both by us and by others. Which is a good thing; that’s what we’ve been trained to do. But there are potential downsides.

-

-

- Our expertise can cause us to be needlessly critical in our thinking.

- We may unnecessarily share our critical thoughts with others.

- We may become inappropriately critical of others.

- Our heightened sensitivity to mistakes may impede our own and other people’s enjoyment of experiences.

-

For instance, in the first example given above, I’m a wine expert so I couldn’t help but notice that the wine was served a bit too warm, but I didn’t need to share that with our guests. By emphasizing the issue, I probably sullied my guests’ opinion of the wine and even my own.

In the second example, I’m a professional musician so I can’t help but notice when mistakes are made in a public performance, but there was no benefit in voicing my observations to others. And, noticing and focusing on the error might have even prevented me from enjoying the groups’ playing in the moment.

Relative to the third bullet point, I’m not an expert in linguistics, I just happened to be familiar with the word that was spoken. It was inappropriate for me to correct the pronunciation.

By definition, a subject matter expert knows many aspects of her domain, which includes both positive and negative insights. But we must be careful about when and what we share with others.

-

- A nutritionist notices that though a dessert served at a dinner party may be tasty, it’s not healthy. But is it appropriate for her to voice her expertise?

- A car aficionado knows that the car you just bought has a history of being problematic, but should he tell you?

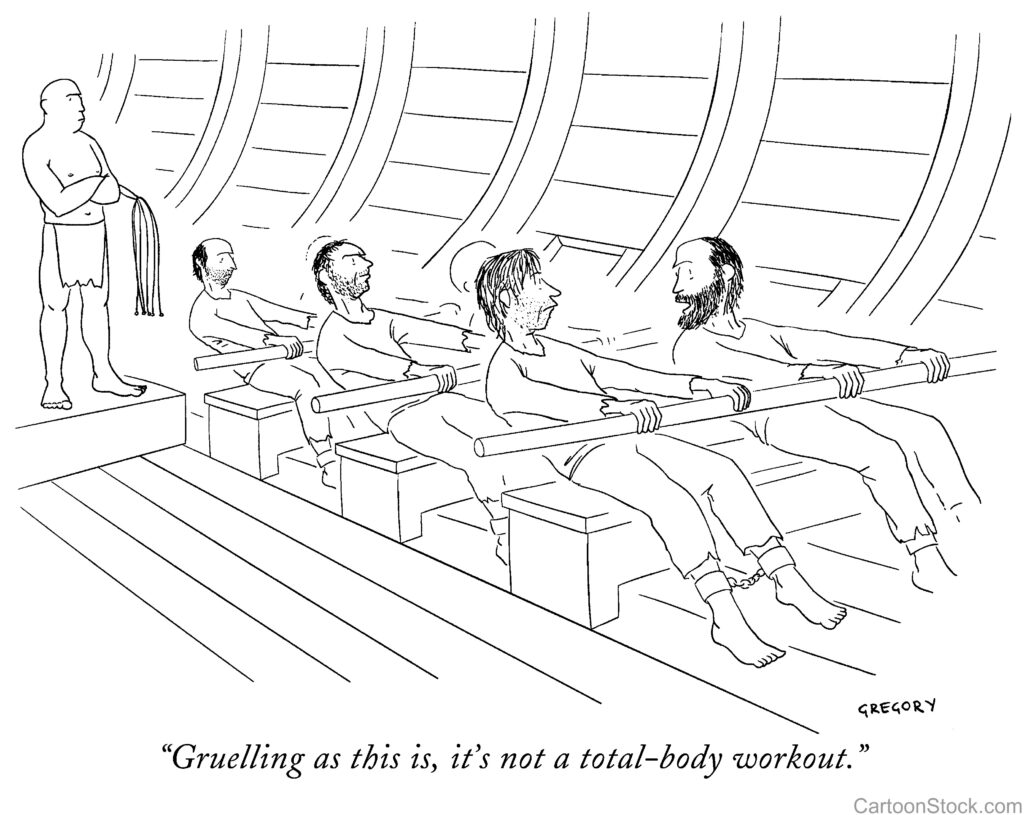

The story is told of an English professor who was running late to teach a class. He was speeding down the highway, heading toward the college, when a policeman pulled him over.

Policeman: “Sir, you were driving fifteen miles per hour over the speed limit.”

Professor: “I’m so sorry. I’m late for a class I’m teaching at the college.”

Policeman: “Well, okay. This time I’ll just give you a warning. You can go. Drive safe.”

Professor: “Thanks…you mean drive safely…”

Policeman: “On second thought, stay right where you are.”

And he wrote him a speeding ticket.