The “curse of knowledge” occurs when a person has such mature and advanced knowledge in a specific area that he cannot remember what it’s like to not have this knowledge. This makes it harder to identify with people who don’t have this knowledge base. It also inhibits our ability to explain things in a manner that is easily understandable to someone who is a novice.

Some examples will help.

-

-

- I learned to read music when I was 18 years old. Fifty-two years ago. Currently, when I direct an amateur choir I sometimes get frustrated at mistakes the singers make because I have forgotten what it’s like to not be able to read music.

- When I turned 60 my personal physician told me to start taking a baby aspirin every day. I asked, “What is a baby aspirin?” He looked at me like I had just fallen off the back of a turnip truck. He knew what a baby aspirin is, but I didn’t.

- In graduate school I took a course in statistics. The professor was a well-known expert, but he was a bad teacher. He knew the material so well, he just couldn’t fathom what it was like to not know principles of statistics. I soon dropped the course.

-

When you suffer from the curse of knowledge you assume that other people know what you know, which causes you to think that people understand you a lot better than they really do.

In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, December 2006, Chip and Dan Heath wrote:

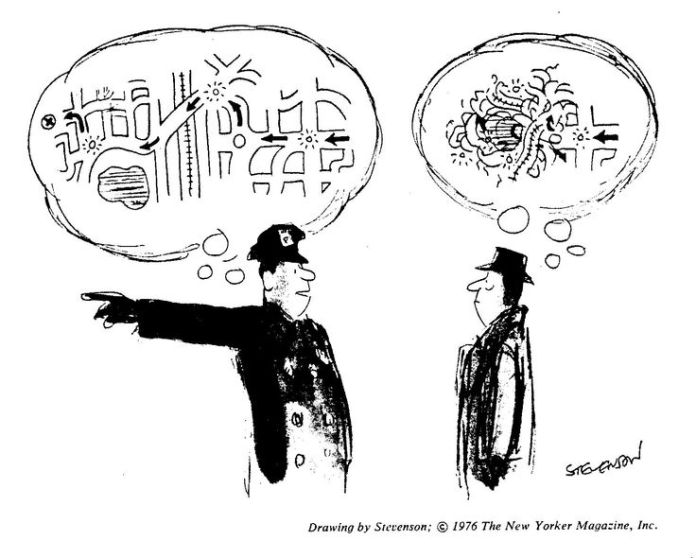

“In 1990, a Stanford University graduate student in psychology named Elizabeth Newton illustrated the curse of knowledge by studying a simple game in which she assigned people to one of two roles: ‘tapper’ or ‘listener.’ Each tapper was asked to pick a well-known song, such as ‘Happy Birthday,’ and tap out the rhythm on a table. The listener’s job was to guess the song.

“Over the course of Newton’s experiment, 120 songs were tapped out. Listeners guessed only three of the songs correctly: a success ratio of 2.5%. But before they guessed, Newton asked the tappers to predict the probability that listeners would guess correctly. They predicted 50%. The tappers got their message across one time in 40, but they thought they would get it across one time in two. Why?

“When a tapper taps, it is impossible for her to avoid hearing the tune playing along to her taps. Meanwhile, all the listener can hear is a kind of bizarre Morse code. Yet the tappers were flabbergasted by how hard the listeners had to work to pick up the tune.

“The problem is that once we know something—say, the melody of a song—we find it hard to imagine not knowing it. Our knowledge has ‘cursed’ us. We have difficulty sharing it with others, because we can’t readily re-create their state of mind.”

Applications

-

-

- When you’re functioning in your area of expertise—particularly if you’re relating to people who are not experts in your field—don’t fall prey to the curse of knowledge. Try to communicate to them as if you had just learned the subject.

- Periodically, enter into situations in which you’re the beginner, which will remind you of what it’s like to be the neophyte.

- Our understanding of the “curse of knowledge” syndrome should inform our approach to communication, reminding us of how very difficult it is to communicate well (“What I’m saying is clear in my mind; why aren’t you getting it?”).

-

The first step to avoiding the curse is to recognize that it exists and how difficult it is to overcome. Psychologist Steven Pinker said, “Anyone who wants to lift the curse of knowledge must first appreciate what a devilish curse it is. Like a drunk who is too impaired to realize that he is too impaired to drive, we do not notice the curse because the curse prevents us from noticing it.”