I recently bought a bottle of wine that had an odd name – Pessimist.

It’s a blend of red grapes from Paso Robles California.

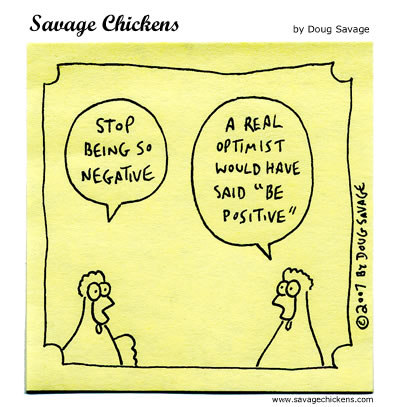

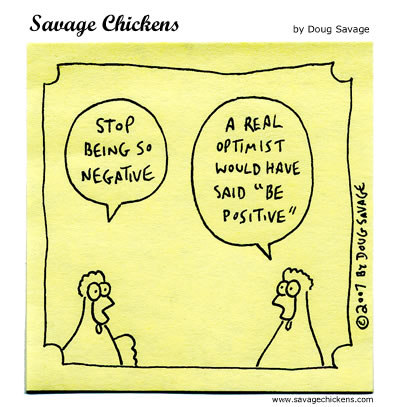

On the label the winery attempts to explain the name by quoting a trite phrase, “A pessimist is never disappointed.” (I think the same could be said of an optimist.)

It’s a lame name and anemic explanation.

In this post, let’s focus on optimism.

Optimism is a general disposition that expects the best in all things. Synonyms include anticipation, confidence, elation, enthusiasm, and expectation.

I like the balance implied in the term realistic optimist. Be a realist about the present and an optimist about the future.

We must embrace reality otherwise we live in wishful thinking and naivety. So identify and embrace what is— both that which is good and bad—and then be optimistic about how to deal with reality.

Finding temporary and specific causes for misfortune is the art of hope. Finding permanent and universal causes for misfortune is the practice of despair.

Martin Seligman, a noted psychologist who has spent his career focusing on theories of well-being and positive psychology., says: “Each of us carries a word in our heart. For some of us the word is ‘yes.’ Yes, we believe we can succeed. Yes, we can learn. Yes, we can make a difference. Others carry a ‘no,’ with all the negative baggage that accompanies it. We must realize which word we carry and how it enhances or inhibits our lives.”

What “word” do you harbor in your heart?

Fortunately, being an optimist or pessimist is a choice we make. It’s not a genetic pre-disposition over which we have no control. Choose to be an optimist. It may take time and effort to reprogram your thinking, responses, and behaviors, but it can be done.

Winston Churchill was the consummate realistic optimist. Here is an excerpt from a speech he gave before the British House of Commons on June 18, 1940. After the fall of France to the Nazis, many in England felt defeated and a sense of resignation and impending doom hovered over the populace. While acknowledging the gravity of the situation, Churchill, nevertheless, spoke a message of hope and optimism that actually promoted a firm resolve and determination in the hearts of his countrymen.

What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, “This was their finest hour.”

Back to the wine. I was disappointed in the Pessimist. It lacked tannin, it was one-dimensional and fell apart about 45 minutes after popping the cork. I suppose I’m pessimistic about Pessimist.